|

|

Review: “Live from Cape Canaveral”

by Jeff Foust

Tuesday, September 4, 2007

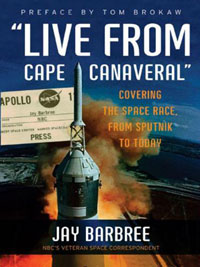

“Live from Cape Canaveral”: Covering the Space Race, from Sputnik to Today

by Jay Barbree

Smithsonian Books, 2007

hardcover, 336 pp.,illus.

ISBN 978-0-06-123392-0

US$26.95

A month from today will be the 50th anniversary of the launch of Sputnik and the generally accepted beginning of the Space Age. Thus, it should be little surprise that a number of books are arriving on bookstore shelves that look back at that event or the history of space exploration in general, either from those who directly participated in those events or from historians and others who later studied them. Jay Barbree, in “Live from Cape Canaveral”, provides a unique perspective: that of a journalist who covered the American space program since virtually its inception.

Barbree has the distinction of being the only journalist to cover every American manned spaceflight, from Alan Shepard’s suborbital Mercury flight in 1961 to the latest shuttle mission last month, for NBC radio and television. In the book, he mixes a history of the space program with anecdotes involving either him and/or the astronauts, in particular the original seven. About two-thirds of the book is devoted to that “golden era” from the program’s inception through Apollo-Soyuz in 1975; the last third, which covers the shuttle program (as well as a brief digression on covering the presidency of fellow Georgia native Jimmy Carter), focuses primarily on a few events, including the Challenger and Columbia accidents as well as John Glenn’s 1998 shuttle flight.

| If nothing else, “Live from Cape Canaveral” illustrates the differences in how the media covered the space program over the last half-century. |

“Live from Cape Canaveral” contains a lot of what might be considered historical “filler” information: descriptions of key events in the space program that are, or at least should be, familiar to most readers, including Shepard’s and Glenn’s Mercury flights, the landing of the Apollo 11 lunar module, and the Challenger accident. These descriptions don’t add much to the book, since they don’t add either information that Barbree had previously only been privy to, or his own perspective on those events. Likewise, the book contains a number of anecdotes, usually involving the original seven astronauts, complete with detailed dialogue, even though Barbree was neither a participant nor a witness. (There’s also the oversimplified, highly-compressed discussion on page 53 of how President Kennedy decided to carry out the Apollo program.) Far more interesting are the stories by Barbree of his work in covering those missions, including the legwork and effort needed for scoops, whether it was an early Atlas launch, Project Score, that carried a tape-recorded message from President Eisenhower, or the reporting in the days after the Challenger accident to identify the cause of the tragedy.

If nothing else, “Live from Cape Canaveral” illustrates the differences in how the media covered the space program over the last half-century. The differences go beyond just the level of attention paid to the exploits of the early Space Race compared to the relative disinterest in today’s program. The relationship between astronauts and the media—at least those who covered the space program closely—appears much closer than it does today. The two often socialized together, and astronauts were willing to share their thoughts or concerns about the program with reporters: Barbree recounts one such conversation in a Florida nightclub with Gus Grissom about the astronaut’s concerns regarding Apollo not long before the fatal Apollo 1 fire. Reporters, in turn, tended to look the other way about the astronauts’ peccadilloes, be they racing cars or allegations of infidelity. (In one extreme case, a “sleazy” private investigator offered Barbree an audiotape that purportedly contained evidence of an extramarital affair involving an astronaut; Barbree said he would check with his bosses, and then promptly erased the tape.) That intimacy between the press and the astronaut corps appears lacking today—Barbree’s chapters on the shuttle program lack the same anecdotes about astronauts that pepper his earlier chapters—which is not surprising given the changes in the level of interest in the space program, not to mention the rise of the 24/7 news cycle and gotcha journalism. (How likely would that audiotape have made its way to the public today, in an era of Drudge, TMZ.com, and ultracompetitive news networks?) Whether or not that change is a good thing is open to debate, but it does remind us that recapturing the spirit of Apollo—long the goal of space advocates seeking to reinvigorate NASA—is far more difficult than simply deciding to return to the Moon.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site and the Space Politics and Personal Spaceflight weblogs. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone, and do not represent the official positions of any organization or company, including the Futron Corporation, the author’s employer.

|

|