The case for shuttle-derived heavy liftby Thomas Olson

|

| For Moon, Mars and beyond, NASA could indeed utilize Shuttle-C configurations, if they so chose. But the key question becomes, who controls it? |

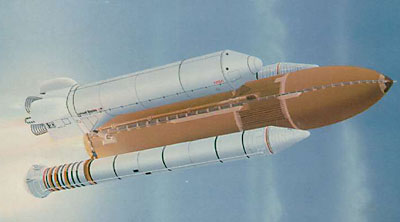

Given present development timeliness for private-alternative horizontal-launch systems, and considering there is approximately an 8x speed differential and a 64x energy differential between sub-orbit and orbit, significant development is believed to be needed; it was also posed that, despite the new vertical boosters under development in Europe and Russia, neither offer sufficient load capacity for heavy-lift vehicles (HLVs) or orbital tourism at reasonable prices. It was suggested that we could conceivably modify some present HL-20-like Crew Exploration Vehicle (CEV) designs for tourist use, seating 6-8 people, and launched in-line atop a Shuttle-C HLV stack. (For that matter, it was even theorized that if 8-10 such craft could be somehow integrated, one could conceivably launch 60-80 tourists in one shot!)

Tourism aside, my “caller” was concerned with preserving US heavy-lift capacity, not only from the point of view of national “ownership” and global competition, but simply to prevent reinventing the wheel and opting for a potentially expensive and time-consuming “blank sheet” approach. For Moon, Mars and beyond, NASA could indeed utilize Shuttle-C configurations, if they so chose. Following Aldridge guidelines would appear, then, to open the door to some private sector activity in due course. But the key question becomes, who controls it?

Today, United Space Alliance, a joint venture of Boeing and Lockheed Martin, does. On the theory that “reforming” USA from within and adding corporate business efficiencies and large scale private customers, the resource is preserved, the US maintains its economic lead in space, and we can accelerate the development cycle for orbital tourism, by concentrating more on spacecraft and market development, and less on boosters.

But to achieve this, we must either change the culture of USA from within or somehow wrest control from without. How could that be done? How might we work around it if we can’t?

So, I turned to about a half-dozen key people in Colony Fund’s Advisory Board and posed these questions to them. I received a lot of great input, in short:

- It may be more daunting a task than we realize to effect a culture change within USA, et al, without a lot of outside influence—beginning with NASA itself.

- As patents on the assets have largely run out, “ownership” issues become blurred, as they’re now largely in the public domain and in the hands of a risk-averse government culture, hence rendering “licensing” schemes chancy.

- The assets themselves are technologically obsolescent and simply too expensive and non-competitive to operate even with private sector efficiencies.

- As the NASA/shuttle “cult” (to borrow Homer Hickham’s distinction) barred the door for private operations for so long, private-launch “mammals” began to work around the Shuttle “dinosaur” and craft more innovative, robust, low-cost solutions that are beginning to see success,

- Given (4) above, it begs the question of the “necessity” for private sector heavy lift in the near to medium term in the first place.

- While HLV for NASA exploration efforts is presumably needed, there is little visible market for heavy-lift in the private sector, when even small-scale booster companies are scrambling for business. “Build it and they will come” is even less of a viable model for private HLV launches than it was for the failed dot-coms.

- Heavy investment will be needed to repair and upgrade the core infrastructure at KSC before private capital would ever be attracted.

Culture and bureaucracy

As “child” of both Lockheed Martin and Boeing, the culture of USA is virtually identical to both. It is at best very slow to change. Let’s review the basics:

- They bid on contracts. In other words, like any typical NASA/DoD contractor, they do not generally think up new business ideas and then market them in the commercial arena on their own. This comes from a very conservative posture and the nature of doing business with the government the last four decades. USA, Lockheed Martin, and Boeing do not need to move quickly because they are all but invulnerable to market conditions.

- Lockheed Martin, as an example, does not expend large or even medium amounts of capital unless they already have a contract. The one exception might be their Atlas 5 EELV, which burned them badly because of decrease in projected launch demand and a 50/50 Boeing/Lockheed development split.

- Similarly contractors do not take risks. Risks that they do take are normally backed by cost plus fee contracts because of the previous points.

- Potential competitors such as SpaceX, SpaceDev, Scaled Composites, etc. are barely or maybe not even on their radar screen (perhaps for good reason, perhaps not).

- On the other hand, Spectrum Astro has shown what a smallsat company can do to systematically take market share in a relatively short time frame (10 years). But Spectrum has been acquired by General Dynamics. So, it’s conceivable that such “co-opting” by a USA-like large contractor could slow future innovation.

- Ergo, USA, Lockheed Martin, Boeing, etc. view themselves as systems integrators, as opposed to innovators or entrepreneurs.

In a free market consumer choice and customer satisfaction determine cultural evolution. If NASA is the only “customer” of USA, then the agency would have to be the primary driver of change. If NASA is as serious about changing its own culture from within as it claims, then by extension the agency can impose evolution of the cultures of their contractors.

| In a free market consumer choice and customer satisfaction determine cultural evolution. If NASA is the only “customer” of USA, then the agency would have to be the primary driver of change. |

Presently the Boeing/Lockheed combine has a vested self-interest in changing nothing, except to political mandate. The status quo keeps them in the money from the government’s business-as-usual system. The question is: How to make it as profitable for them, yet morph from the government mentality to the corporate mentality? Probably difficult, as we would have to develop a “plan” that shows how private sector “control” of this program can generate more profits for a wider corporate base, with but actual deliverables that get us someplace. (Who would come up with such a plan? Another Aldridge-like commission?) Can we entice USA with commercial payloads big enough to require shuttle-derived HLVs? Where will those payloads come from? (Unknown, right now) Or do we work the other side of the equation and entice space enterprises that may one day require HLVs?

Another problem that makes many suspicious of private shuttle-derived HLV scenarios is the process itself. It takes almost an uncountable number of signatures to launch a shuttle. If you’re the program manager of the non-man-rated cargo-only Shuttle-C, which set of safety procedures are you going to eliminate first, for the sake of private-sector efficiency? If Shuttle-C drops a cargo into the Atlantic, someone will be looking for scalps. How do we make this cost-effective? Now complicate matters by parking a private-tourist CEV on top, with 6-8 passengers… so there goes your “non-man-rated” scenario, and you can now add an extra zero to your insurance liability costs.

Ownership and licensing

Who “owns” the shuttle technology itself? I suppose the first answer that comes to mind is that NASA does, and by extension the US government, and by extension, We The Taxpaying Citizens of These United States—meaning, in other words, nobody really “owns” it. Why? Because as is always the case with public assets no one will risk their political necks to attempt something other than the tried-and-true with those assets.

| Who “owns” the shuttle technology itself? NASA does, and by extension the US government, and by extension, taxpayers—meaning, in other words, nobody really “owns” it. |

The reason that’s a problem is because if you truly “own” a technology asset, in the way that Microsoft owns Windows, you can then license it out to those who can pay the fees, and/or are otherwise deemed capable of using it effectively, safely, under ITAR guidelines, etc. If NASA was a true owner of the technology, and was licensing it to USA right now, they could just as easily license it out to any other group with sufficient resources. USA would be an equal licensee on a level field, and would also be feeling some competitive pressure to excel and promote efficiency, simply by the presence of the “new kids” sharing launch facilities. As NASA still controls KSC itself, there would presumably be flexibility for private launch options. (The next step, of course, would be to get KSC out of NASA control as well, perhaps under a “port authority” model, but also difficult politically). “Privatizing” the shuttle components would encourage the licensees to put it to more efficient use.

The ownership issue, though, may be moot. Since it was developed over 20 years ago, all the original patents have run out. As for shuttle derivatives, if they were patented, they are owned by the patent holders and if not, they are in the public domain. However, technology can still be transferred because a patent isn’t necessarily enough to recreate the shuttle system from scratch, and would add prohibitive costs. Politically, this could also be mandated by Congress along the lines of the Bigelow model, i.e., auction off exclusive rights to shuttle technology.