In search of other Earthsby Jeff Foust

|

| “It’s Earth-like in the sense that it’s about the same size and mass, but of course it’s extremely unlike the Earth in that it’s at least 2,000 degrees hotter,” said Winn of Kepler-78b. |

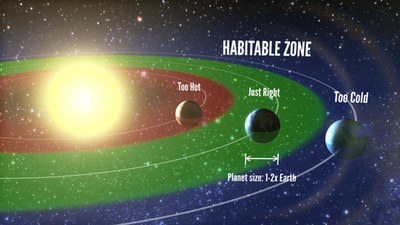

As fascinating (and, sometimes, as perplexing) as these exotic worlds may be, what’s of real interest to many scientists—and, arguably, to the general public—is the search for planets like the Earth, at least in some key parameters. The term “Earth-like” is often applied to these planets, although whether they are truly like the Earth in their ability to support life—have liquid water and atmospheres, for example—is far beyond the capabilities of current telescopes and spacecraft to confirm. For now, astronomers have set their sights on finding planets similar in size to the Earth that orbit in their stars’ “habitable zones,” where temperatures would support the presence of liquid water on their surfaces, if such planets had any. These worlds could still turn out to be barren and lifeless, but they help constrain just how frequent potential Earth-like planets are.

Detecting these potentially Earth-like worlds is a challenge, though. Last week, astronomers announced the discovery of the first Earth-sized exoplanet whose density, and thus bulk composition, is also like the Earth. Planet Kepler-78b was initially found in data collected by NASA’s Kepler spacecraft, which monitors more than 100,000 stars for minute, periodic decreases in brightness caused when a planet transits, or passes in front of the star, blocking a tiny fraction of the star’s light. Kepler has detected thousands of “planet candidates,” although to date only 156 have been confirmed as planets by other observations.

Kepler-78b showed promise as a small world closely orbiting a star only slightly smaller than the Sun. Two teams of astronomers followed up on the Kepler discovery with groundbased observations using the radial velocity technique, measuring the Doppler shift in the star’s spectral lines caused by the gravitational tug of the orbiting planet. While the Kepler observations could determine the size of the planet, based on the fraction of starlight it blocked, the radial velocity measurements offered a means to measure the planet’s mass.

The results, published last week in the journal Nature, found that Kepler-78b has a radius about 1.2 times that of the Earth and a mass 1.7 times that of the Earth, a determination made independently by the two separate teams. That combination of size and mass means the planet has approximately the same density as the Earth, and thus presumably a similar bulk composition of rocks and metal.

Although similar in size and density to the Earth, no one would consider Kepler-78b to be terribly Earth-like. The reason? It orbits its star at a distance of only about 1.5 million kilometers, completing a single orbit in just 8.5 hours. Its surface temperature would be more than 2,000°C, hot enough to melt any rocks on its surface. Astronomers reporting the discovery frequently used the same word to describe Kepler-78b: “hellish.”

“It’s Earth-like in the sense that it’s about the same size and mass, but of course it’s extremely unlike the Earth in that it’s at least 2,000 degrees hotter,” said Josh Winn, an MIT associate professor who was part of the team that studied Kepler-78b, in a statement. “It’s a step along the way of studying truly Earth-like planets.”

“It’s an existence proof, and it shows us that Nature knows how to make rocky, Earth-sized planets,” said Andrew Howard of the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii, in a teleconference with reporters Friday.

Kepler-78b has also presented astronomers with another puzzle: why it exists in the first place, so close to its star. “This planet is a complete mystery,” said David Latham of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in a statement. “We don’t know how it formed or how it got to where it is today. What we do know is that it’s not going to last forever.”

That last comment reflects that Kepler-78b is doomed. Its orbit will gradually delay to the point where the star’s gravity will rip the world apart, which astronomers predict will take place in about three billion years.

While Kepler-78b is not Earth-like, the discovery of a planet with a similar size and density as the Earth raises the prospects that other worlds, in more hospitable orbits, exist around other stars. Measuring the frequency of such worlds, a parameter often called “eta-Earth,” is one of the goals of the Kepler mission.

| “With today’s analysis,” said Marcy, “we’re learning that Earth-sized planets having the temperature of a cup of tea are common around Sun-like stars.” |

In a paper published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), one team of astronomers offered its own estimate for the value of eta-Earth. The study, led by Erik Petigura of the University of California Berkeley, analyzed data from 42,000 stars collected by Kepler. That analysis turned up 603 planet candidates, including 10 with sizes similar to the Earth and orbiting roughly within the star’s habitable zone.

Petigura and colleagues then used those observations to estimate the total fraction of stars that have such planets. That involved modeling to correct for stars whose solar systems are not aligned with the Earth to allow for transit observations, as well as to account for stellar variability that can mask the drop in brightness caused by a transiting exoplanet. “After correcting for missed planets, we found that 22 percent of Sun-like stars harbor an Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone,” he said Friday in a call with reporters.

That conclusion excites some astronomers who have worked for years to look for exoplanets. “I feel a little tingly, that this is such a special moment,” said veteran exoplanet astronomer Geoff Marcy of UC Berkeley. “With today’s analysis, we’re learning that Earth-sized planets having the temperature of a cup of tea are common around Sun-like stars.”

Does this finding mean that Kepler’s goal, of determining eta-Earth, has been accomplished already? Natalie Batalha, deputy science team lead for the Kepler mission at NASA’s Ames Research Center, said Friday there’s a lot more work ahead for the Kepler team, including a backlog of data from the mission yet to be fully analyzed. “We have a whole another year of data to analyze,” she said. “My own opinion is that we have about three years of work left to identify the rest of these planets.”

The Berkeley study, though, is still exciting, she said. “You can imagine that everyone working on Kepler data around the globe has had their ears perked up” by this finding, she said. When a preprint of the paper was available last week, she said, the Kepler team eagerly reviewed it, crosschecking its findings with their own analysis. “By Thursday evening, my office was crowded with people actively talking about the details of the work. The mood was very festive and the dialogue was very productive.”

The findings of the PNAS paper will also be presented today at the Second Kepler Science Conference, taking place as this week at NASA Ames. A month ago, the fate of the conference looked uncertain, as the government shutdown put a hold on preparations. At the same time, a number of prominent astronomers were threatening to boycott the conference after learning that several Chinese scientists were barred from participating, a ban linked to NASA policies tied to a Congressional ban on US-China space cooperation. That ban was later lifted by NASA, blaming it on a miscommunication, and the end of the shutdown cleared the way for the conference to take place on schedule.

Another issue that will likely be discussed at the conference is the uncertain future of Kepler itself. Earlier this year, the second of four reaction wheels on the spacecraft failed, depriving the spacecraft of the ability to point accurately enough to continue its primary mission of exoplanet studies. Efforts to try to recover one of the failed wheels ended this summer, and the project solicited proposals for alternative missions that don’t require the same pointing accuracy (see “Kepler seeks a new mission”, The Space Review, August 19, 2013).

| “You can imagine that everyone working on Kepler data around the globe has had their ears perked up” by this finding, Batalha said. |

The project received about 40 proposals for alternative uses of Kepler, which the project is now reviewing. “They were subjected to review and scrutiny by the engineers to try and decide what was feasible and what is scientifically compelling,” Batalha said Friday. “We will be submitting a report to NASA Headquarters soon, later this month, to summarize the results of that study.”

Batalha didn’t say when NASA would decide on what alternative mission, if any, it would use Kepler. Any other use of Kepler would likely have to be approved by NASA during a “senior review” of ongoing astronomy missions early next year, as the agency determines if the science these missions perform is worth the cost of continuing to operate them, a particularly difficult challenge in the current budget environment.

Although Kepler may not make any more observations in search of Earth-sized exoplanets, there is still plenty of work ahead of the team. In addition to analyzing the backlog of data from Kepler, Batalha said they are working to improve the data they already have. “What we’d like to do to make up for not having as much data as we’d thought we’d have is to really dive down into the weeds and apply innovative techniques to give Erik [Petigura] better brightness measurements,” she said.

Another issue is to confirm that the planet candidates found in the Kepler data are, in fact, planets. Unlike Kepler-78b, the ten Earth-sized exoplanets found in their stars’ habitable zones can’t be confirmed with even the best radial velocity systems in use today given their more distant orbits. For such planets, Marcy said, “the gravitational yanking on the host star is too feeble to jerk the star around enough to detect it with the Doppler technique we normally use.”

Batalha said the Kepler team is taking another approach with such exoplanets by trying to rule out other natural phenomena that could generate similar data. “We’re doing the hard work to scrutinize these most interesting planet candidates in order to really create a reliable sample and know we’re not being confounded by other astrophysical signals,” she said.

Marcy, in Friday’s call, praised NASA for taking the “bold move” to fly the Kepler mission, as well as the team of scientists and engineers working on the mission. “It has been a joy to work with these folks,” he said. “It’s been wonderful to work within a team of inspired and technically brilliant people, all working towards a common goal, the goal of learning if our home planet Earth is some kind of cosmic freak or, instead, a common occurrence within the Milky Way galaxy.”