A small step for Mars settlement, but a giant leap of funding requiredby Jeff Foust

|

| “There missions are the first step in Mars One’s overall plan of establishing a permanent human settlement on Mars,” Lansdorp said. |

Inspiration Mars’s plans, though, pale in comparison of those by another nonprofit organization, Mars One. The Dutch-based venture seeks to send people to Mars, but rather than a flyby, Mars One would land them there—permanently, in the hopes of establishing a permanent settlement whose initial missions would be funded, in part, by selling media rights and with an astronaut selection process that has parallels to reality television shows. Some consider it visionary; others, insane.

While discussion of the viability of such missions continues, Mars One took a small step last week towards its goal of humans on Mars. At a lightly-attended press conference in on a snowy Tuesday morning in Washington, Mars One announced it had issued contracts to two leading space companies to study concepts for an initial robotic mission that would launch in 2018.

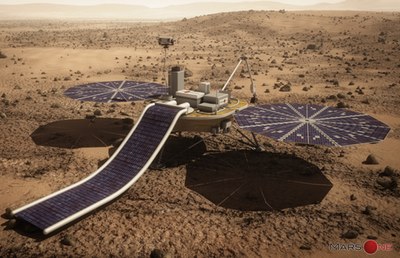

That mission, as currently planned, will consist of two spacecraft. Lockheed Martin will study concepts for a lander based on the same hardware used for the Phoenix Mars Lander spacecraft that successfully landed on Mars in 2008, as well as for the upcoming InSight Mars lander mission. Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd. (SSTL) will study designs for an orbiter that would serve as a communications relay from the Martian equivalent of geosynchronous orbit.

The lander, Mars One CEO and co-founder Bas Lansdorp said, will serve primarily as a technology demonstrator. Its payload will include an experiment to test the production of liquid water and another to test a thin-film solar panel proposed for Mars One’s later crewed missions. Calls for proposals for those two experiments will be issued in the first half of next year. In addition, a camera will provide live continuous video of the Martian surface during the day, relayed back to Earth via the communications orbiter.

In addition, Lansdorp said Mars One plans a “worldwide university challenge” where students can propose experiments to fly on the lander, as well as science education competitions for younger students that would incorporate payloads of some kind on the mission. He said Mars One is in discussions with a number of potential partners to sponsor those competitions, as well as unspecified “very exciting, very exclusive PR events.”

“There missions are the first step in Mars One’s overall plan of establishing a permanent human settlement on Mars,” Lansdorp said. “We believe we are in very good shape to make this happen.”

| A crowdfunding campaign “will help us fund part of this mission, but also it will show our partners, sponsors, and investors that this is something that actually the whole world wants to happen,” said Flinkenflögel. |

Lockheed Martin has already started studies of the proposed lander, said Edward Sedivy, chief engineer for civil space at Lockheed Martin Space Systems Company. That work is looking how to integrate the lander with the orbiter on the same (as yet unselected) launch vehicle, and how to provide the maximum flexibility for the suite of payloads the lander could carry. “It’s a great opportunity,” he said. “We are really excited about a few aspects of this mission,” such as the fact that is a private mission with international collaboration, as well as the educational outreach potential it has.

“We’re just as excited as our colleagues at Lockheed Martin,” said Sir Martin Sweeting, executive chairman of SSTL, speaking via videoconference from his offices in the UK. “It’s been a dream for us at Surrey for many years.” SSTL has made a name for itself in the space industry as a pioneer and leading developer of small satellites, and plans to leverage that experience for the communications orbiter. In particular, he said SSTL would draw upon its experience developing the GIOVE demonstration satellite for the Galileo navigation system, as well as its joint work with German company OHB-System to build the first 22 operational Galileo satellites.

For now, the two companies have signed contracts only to perform mission concept studies, not for the spacecraft themselves. Lansdorp said those studies should be done by the middle of 2014, “and after that we will take the next steps with those companies.” He said the contract with Lockheed Martin is valued at a little more than $250,000, while the SSTL contract is worth €60,000 ($82,000).

From a technical standpoint, there’s little doubt that either company can develop the spacecraft Mars One proposes to send to Mars, given the experience the two companies have and the plans to make use of heritage hardware, such as the lander that, in the one illustration provided by Mars One, looks strikingly similar to the Phoenix lander. The bigger question whether Mars One can afford those missions.

Mars One CEO Bas Lansdorp discusses his organization’s plans for a robotic lander and orbiter during a December 10 press conference in Washington, DC. (credit: J. Foust) |

For now, few doubt Mars One’s ability to pay for the study contracts. While Lansdorp would not disclose how much money Mars One has raised to date, he did say that the organization had received “just over” $200,000 in donations. (According to the Mars One web site, the organization has raised, though donations and merchandise sales, $183,870 through the end of October.) In conjunction with the mission announcement, Mars One also started a crowdfunding campaign to raise $400,000 to support mission development. As of early Monday, December 16, the campaign had raised a little more than $55,000.

| After the press conference, Lansdorp said he estimated the total mission cost would be less than NASA’s InSight mission, which is capped at $425 million plus launch costs. |

That crowdfunding campaign, a Mars One official said, is designed as much to demonstrate public interest in the project as it is to directly raise money. “It will help us fund part of this mission, but also it will show our partners, sponsors, and investors that this is something that actually the whole world wants to happen and wants to contribute to,” said Suzanne Flinkenflögel, director of communications for Mars One, at the press conference.

Just how much those missions will cost, and how Mars One will raise the money, remain unclear. Lansdorp said at Mars One had a “ballpark figure” in mind for the mission cost, but declined to share it publicly; mission cost estimates would come out of the concept studies Lockheed and SSTL will perform. After the press conference, Lansdorp said he estimated the total mission cost would be less than NASA’s InSight mission, which, as part of the agency’s Discovery program, is capped at $425 million plus launch costs.

As for raising the money for the mission, Lansdorp was similarly vague. “We’re having really good discussions with partners,” he said, citing in particular interest in the planned university payload competition. “There are a lot of companies interested in associating themselves with that.” Such partners would be the primary source of funding for the mission, he later said.

Mars One has delayed the mission by two years, to 2018, in part to give it more time to line up partners for the mission. A robotic precursor mission was, in the original Mars One architecture, planned for launch in 2016. “This new schedule allows for time for the development of the two spacecraft, for finding subcontractors for the experiments we will fly on the spacecraft, and to organize a number of competitions that Mars One wants to implement around these first missions,” Lansdorp said.

That two-year delay will percolate through the rest of Mars One’s overall schedule, pushing back the first human mission to no earlier than 2025. Mars One will go ahead with the next major step in selecting the crew for that mission soon despite that delay. “We promised our applicants know that we would let them know by the end of 2013 if they passed on to round number two or not,” Lansdorp said. “That’s still our plan.” Lansdorp said in August he expected between 10 and 30 percent of the applicants to make it to the next round (see “One year after the seven minutes of terror: the state of Mars exploration”, The Space Review, August 5, 2013.)

Lansdorp said that Mars One received “more than 200,000 applications” when the deadline for applications passed at the end of August. However, as noted in the past, the number of completed applications eligible for consideration for the next round may be significantly smaller than that. One part of the application process required people to provide a brief video explaining their interest in the Mars One mission. The Mars One website has fewer than 2,650 such applicant videos online. Even if a large fraction of applicants elected to make their videos private—a somewhat odd choice for a mission whose crew selection process will later feature televised competitions—it suggests that the number of applicants eligible for selection to the next round is on the order of several thousand, not 200,000.

As that astronaut selection process continues, the challenge facing Mars One will be to demonstrate that it can carry out a robotic mission that, while nowhere near as expensive or difficult as a human mission, will be neither cheap nor easy. Last month, Inspiration Mars founder Dennis Tito estimated he could raise a few hundred million dollars for a human Mars flyby mission, with NASA picking up the rest of the cost. Mars One will need to raise a similar amount of money for its robotic mission, but without the cachet of sending people there on that mission. If it can’t do that, raising the billions for one-way human missions would be out of the question.