Scaling up alternative space funding sourcesby Jeff Foust

|

| TC2M has an estimated cost of $25 million. “We want the primary mode of contribution to be through crowdfunding,” Briere said. |

That effort was far and away the largest space-related crowdfunding effort ever, and among the largest of any kind to date (the 39th largest ever, according to a Wikipedia list of such efforts, between a video game and a smartwatch.) Now, a student-led project seeks to shatter that record as it raises money to send a spacecraft to the surface of Mars.

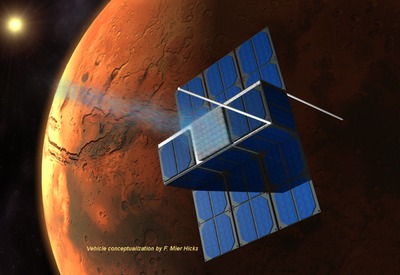

At a June 23 press conference in Washington, representatives of Time Capsule to Mars (TC2M) said they plan to use crowdfunding as a major source of the $25 million needed to carry out their project. That project, first disclosed at the Humans to Mars Summit two months earlier, seeks to send a CubeSat-class spacecraft to Mars, depositing on its surface a time capsule of photos, videos, and other records (see “Mars missions on the cheap”, The Space Review, May 5, 2014).

The mission features a number of technical and programmatic firsts. TC2M plans to be the first student-built interplanetary mission, as well as the first CubeSat-class spacecraft to go to Mars. The spacecraft would also be the first mission beyond Earth orbit to test a new kind of electric propulsion, called ion electrospray thrusters, currently under development at MIT.

TC2M leaders are also hoping for a financial first. “On top of it all, we hope that this mission will be the largest crowdfunded effort in history,” said Emily Briere, a senior at Duke University who is the mission director for TC2M. A feasibility study estimated the mission’s cost at $25 million. “We want the primary mode of contribution to be through crowdfunding,” she said.

“This was an enormous opportunity for a business student who is passionate about space get involved with the project and make a difference,” said Jon Tidd, a graduate student at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business and the director of fundraising and marketing for TC2M, announcing the crowdfunding campaign at the Washington press conference.

A major reason behind going the crowdfunding route, versus simply seeking corporate or other large donations, was to engage the public. “We were looking for opportunities to fund this mission in a way that would involve as many people as possible,” Tidd said. “We came up with the idea of simplified 99-cent upload for a single digital photo.”

Right now, TC2M is accepting any image, up to 10 megabytes in size, for $0.99 each. Those images will be included in the TC2M spacecraft and sent to Mars. Later, project officials said, they will expand the uploads to include videos and other media, and are also considering, like many other crowdfunding campaigns, higher donation tiers with various rewards yet to be determined. They’re also considering “sponsored uploads,” where a donor agrees to pay for uploads from a particular country or region, in order to ensure participation from developing nations as well.

While most crowdfunding campaigns make use of a platform like Kickstarter or Indiegogo that handles payments (and takes a cut), TC2M is, for now, running their campaign independently. Tidd said that technical issues associated with uploading photos kept them from using those other platforms, but would not rule out using them in the future.

Another advantage of using their own platform is that TC2M does not have a firm, near-term deadline. Most crowdfunding efforts on Kickstarter and similar sites run for anywhere from a month to a few months. TC2M has not announced a specific timeline for their mission beyond launching in the next five years. (At the press conference, Briere said TC2M did have an arrangement for the spacecraft’s launch, but that the details about it, including with whom they’re working, remain proprietary.)

| “We were looking for opportunities to fund this mission in a way that would involve as many people as possible,” Tidd said. “We came up with the idea of simplified 99-cent upload for a single digital photo.” |

TC2M is open to other sources of funding, including corporate donations; the TC2M website lists a number of companies as sponsors, including Aerojet Rocketdyne, ATK, and Lockheed Martin. Even if all $25 million for the mission is raised through crowdfunding, it will not be, as the project claims, the largest crowdfunding campaign to date: the “Star Citizen” video game project has raised more than $47.6 million to date, primarily through its own website.

Right now, the TC2M team is small, with about 25 to 30 students at four universities: Duke, MIT, Stanford, and the University of Connecticut. Briere said that while TC2M will be active this summer—a mission review is planned for later this month at Stanford—they hope to increase both the number of participants and participating universities when classes resume in the fall.

TC2M is the biggest, but hardly the only, example of the increased use of crowdfunding by space-related endeavors. Last week, SpaceIL, one of the teams in the Google Lunar X PRIZE, completed a major crowdfunding campaign, exceeding its goal of $240,000 by more than $40,000. The team plans to use the funds to support spacecraft development and educational outreach activities. (That success, though, is dwarfed by a $16.4-million donation SpaceIL received from the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Family Foundation in April.)

Space-related crowdfunding has also expanded beyond building hardware or funding missions. Another ongoing Kickstarter campaign seeks to raise $18,000 to fund an update of the “Integrated Space Plan,” a complex flowchart first developed in the 1980s to show the interrelations of various space infrastructure: “A real and detailed timeline of our future in space for the next 100 years,” as the project’s backers describe it. With a little less than three weeks to go, the campaign has raised a little more than half of its goal.

However, while crowdfunding may be gaining in popularity, it’s not necessarily easy money, as one of the key people behind Planetary Resources’ effort recalls. “It took basically our entire team: we had 30 people in our office, and lots of them were very focused on preparing for months in advance” of announcing the campaign, said Caitlin O’Keefe, director of marketing for Planetary Resources, in a presentation about that effort at the International Space Development Conference in Los Angeles in May.

That effort was also selected by a group of volunteers called “Vanguards” that the company solicited before the campaign started: people were asked to volunteer for a “secret project” and were briefed on it the night before the announcement. “So the next day, when we had our press conference, we had this group of 300 people ready to start promoting” the campaign, she said.

Asked if Planetary Resources would consider doing another Kickstarter campaign, O’Keefe said they would be interested—eventually. “I would love to do another one, because I think it’s really important in terms of education and public involvement,” she said. “I would love to start fulfilling on this one before we start doing another Kickstarter.” [Note: A Planetary Resources spokesperson said Wednesday that the company has already started fulfillment of the Kickstarter campaign’s rewards, and that O’Keefe meant to say that the company wanted to complete that fulfillment before starting a new campaign.]

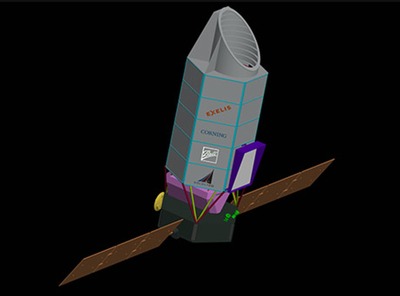

BoldlyGo’s ASTRO-1 spacecraft would carry on science currently done by the Hubble Space Telescope, starting in the mid-2020s, at a cost of roughly one billion dollars. (credit: BoldlyGo Institute) |

Bigger money for bigger missions

Crowdfunding, though, has its limits: even the tens of millions of dollars raised by the most successful campaigns is enough for only the smallest space missions. To do something bigger and more ambitious means seeking alternative funding sources, both conventional and unconventional, as one organization is attempting to do.

Last month, the BoldlyGo Institute, a new nonprofit organization, announced plans to raise private funding for space science missions. They hope to raise large sums of money—on the order of one billion dollars or more—to funding missions that agencies like NASA cannot afford to do.

“We’re replete with outstanding ideas for missions that don’t fly because we’re resource limited,” said Jon Morse, chief executive officer of the BoldlyGo Institute, during a session describing the organization’s plans at the 224th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Boston last month. A typical announcement of opportunity for a NASA mission, he said, might attract a half-dozen proposals that are “worthy and selectable,” but only one gets funded.

Morse, a former director of NASA’s astrophysics division, said that the agency’s science programs are further constrained by flat budgets. “This is a big part of the motivation for the BoldlyGo Institute,” he said. “It is to find new resources for space science.”

| “We’re replete with outstanding ideas for missions that don’t fly because we’re resource limited,” said Morse. |

At the AAS meeting, BoldlyGo unveiled two mission concepts it’s seeking to fund initially. The first is a Mars sample return concept called Sample Collection for Investigation of Mars (SCIM). Rather than land on Mars, SCIM would dive through the Martian atmosphere, collecting dust to return to Earth. SCIM is not a new idea: it was first proposed more than a decade ago and was one of four finalists for the first Mars Scout mission, losing out to the Phoenix Mars Lander.

“It sounds very daring, but it’s actually a really doable mission,” said Laurie Leshin, who was the principal investigator for the original SCIM concept when she was at Arizona State University. Leshin, now the president of Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts, said the organization is working closely with Lockheed Martin, the original industry partner for the mission. “They have lots of ideas about how to do this in new ways,” she said. SCIM’s estimated cost is a few hundred million dollars.

A second, and more ambitious, mission is a space telescope called ASTRO-1. Morse said the mission, still a “strawman concept” at this early stage, would effectively serve as a replacement for the Hubble Space Telescope, doing observations at ultraviolet and visible wavelengths. “It occupies a place in the portfolio that we believe that is doing essential and really exciting science,” he said.

The current ASTRO-1 concept, developed by an industry team of Ball Aerospace, Exelis, and Corning, would use a 1.8-meter primary mirror, somewhat smaller than Hubble’s 2.4-meter main mirror. However, it would use an off-axis design that eliminates the usual obstruction caused by the telescope’s secondary mirror. That, Morse said, provides a better “point spread function” for image quality, and an increased real collecting area, bringing its capabilities closer to Hubble’s.

| “We know that our fundraising is daunting,” Morse acknowledged. “We need to use an all-of-the-above strategy for the SCIM and ASTRO fundraising.” |

While BoldlyGo would like to launch SCIM by the end of this decade—there are favorable launch opportunities in 2018 and 2020—Morse said ASTRO-1 is farther out in the future, most likely in the mid-2020s. “This is for the post-Hubble era,” he said. The mission, he said, would be a “probe-class” mission in NASA parlance, a class of mission with estimated costs of about $1 billion.

Thus, even if BoldlyGo decided to do only those two missions, it would need to raise perhaps as much as $1.5 billion. “We know that our fundraising is daunting,” Morse acknowledged. “We need to use an all-of-the-above strategy for the SCIM and ASTRO fundraising.”

That approach includes fairly conventional philanthropic fundraising. “There’s no avoiding the fact that we will need large donations from individuals, groups, or foundations, contributing significant fractions of the development cost,” he said. “We’re just getting started with this.”

However, BoldlyGo doesn’t plan to rely exclusively on such donations. Morse indicated they were open to a wide array of alternative approaches, like corporate sponsorships. “There’s no reason SCIM couldn’t look like a NASCAR,” he quipped, noting that the spacecraft would return to Earth at the end of its mission and thus providing its sponsors with a round of publicity.

Morse even suggested that scientists themselves could contribute to the development of ASTRO-1 in particular. Each scientist might be asked to provide a couple hundred thousand dollars, spread over several installments, he said. Those funds would not go to the actual construction of the telescope but to support its “scientific productivity” through development of software tools and data archives.

More importantly, though, Morse argued that such funds would help the overall fundraising effort by demonstrating the seriousness of astronomers’ interest in the telescope to other prospective funders. “Scientists showing that they have ‘skin in the game’ will help the overall fundraising effort, because it demonstrates widespread vested interest in the success of the endeavor,” he said.

So far, Morse said at the AAS meeting a month ago, the organization has raised seed funding for its initial activities while working to raise “significant” but unspecified other donations. “I gave up my tenured full professor position at a research university in order to do this full time,” he said, referring to his prior position at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. “I’m going to spend all of my time trying to raise resources to make these kinds of projects happen.”

BoldlyGo is not the first to take the philanthropic route to try and raise large sums of money for space missions. Two years ago, the B612 Foundation announced plans to develop a space telescope called Sentinel devoted to searches for near Earth asteroids that could pose a threat to the Earth (see “A private effort to watch the skies”, The Space Review, July 2, 2012). The foundation planned to raise the estimated $450 million needed for Sentinel through private donations, likening it to fundraising for a museum or university.

Two years later, B612 is still actively raising money, but is circumspect about just how much it’s raised. “We have raised money to do what we’ve done so far,” Ed Lu, the former astronaut who is the CEO of the B612 Foundation, said in a call with reporters in April timed to the release of a video illustrating the impact threat posed by near Earth objects.

Lu likened the foundation to a “Silicon Valley startup” that raises funding in a series of tranches. “We’ve raised money in bunches to pay for technical milestones,” he said, without disclosing how much they’ve raised. “We’ve raised enough to go as far as we have, but we will continue to do this and raise larger amounts over the next several years. We’re not there yet.”

That sentiment—“we’re not there yet”—is true for a number of these ventures seeking unconventional approaches to raise money for missions or other space-related projects. Creative funding approaches may increase the chances of success, but they do not guarantee it.