Witnesses: Space historiography at the handover (part 2)by David Clow

|

| Apollo 13 survived because the flight controllers recognized the errors in their history and quarantined them. |

Aboard the ship, James Lovell recalled a “dull but definite bang--not much of a vibration though… just a noise” ,4 while Fred Haise said later he could feel the docked LM and CSM torquing.5 The MOCR was disoriented as an unexpected story took shape. “All the controllers from the very beginning were calling out their console TM indications and when possible corrective actions. INCO [Instrumentation and Communications Controller] was calling for antenna selections, GNC [Guidance, Navigation, and Controls] was calling out to reopen Prop valves… etc.,” Kranz recalled,6 but at the EECOM console the next eighteen minutes of mission history still held to the false trajectory, as Sy Liebergot felt that the data showed an instrumentation failure. (This was understandable: “As [Jack] Swigert would write later, ‘If somebody has thrown that at us in the simulator, we’d have said ‘Come on, you’re not being realistic.’”7) The MOCR audio reveals no unusual stress in the voices, but Liebergot wrote later that when the actuality finally hit them, “It was unbelievable.”8 “The Apollo 13 failure had occurred so suddenly, so completely with little warning, and affected so many spacecraft systems, that I was overwhelmed,” he wrote. “As I looked at my data and listened to the voice report, nothing seemed to make sense.”9 Liebergot heard a trainee say something that would normally have been unimaginable in the MOCR: “I don’t know where to start.”10

(It should be noted that Sy Liebergot’s request that the tank be stirred at that moment, and not hours later as scheduled, might have saved the lives of the crew. The explosion was inevitable. Had it happened further along, the water and power reserves of the Lunar Module would have been exhausted before re-entry.)11

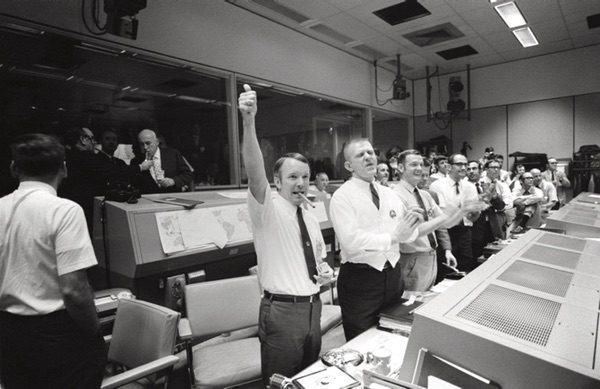

Their actual mission history was so far off their planned one that they had little idea what had come before this to put them there, and at first, little understanding of where this path was taking them. The recovery started about twenty minutes into the emergency. Gene Kranz served notice that the real Apollo 13 mission was starting then and there, asking Sy Liebergot, “Whaddaya think we got on the spacecraft that’s good?”12,13 , Kranz diagnosed the first thing they had to do: end the errors and assumptions, spot what they did not know and did not consider in the corrupted history they had inherited, and start writing a new history of facts. “Let’s solve the problem,” he told his team, “but let’s not make it any worse by guessing.”14

The hardware was ruined, so the only solutions were intellectual ones. Kranz had an ace in his vest pocket:

In the simulations for [Apollo 9] mission SimSup gave us a problem where the LM [Lunar Module] was unable to rendezvous and return to the CSM [Command/Service Module]. We had to invent power down procedures to sustain the LM to allow rescue by the CSM. Also during the actual Apollo 9 mission we did the docked burns with the LM DPS [Descent Propulsion System]…. Using almost the exact procedures we used during Apollo 13. 15

(Sims were not always so productive, as Sy Liebergot noted: “On April 25, 1969, during an Apollo 10 simulation, the CSM sustained a hydrogen leak at 51:15 hours into the mission, which resulted in the loss of all three fuel cells. Unprepared for this kind of failure, the flight control team was unable to save the crew.”16) The process continued during the handover as Glynn Lunney’s Black Team came on-shift. Lunney remembered,

It posed a continuous demand for the best decisions often without hard data and mostly on the basis of judgment, in the face of the most severe in-flight emergency faced thus far in manned space flight. […] During the 87 hours from explosion to recovery, there were likely thousands of spacecraft configuration and mission timeline choices. There were numerous new innovations imagined, perfected and made available on-time. All of these were a vital part of improving the prospect for a safe and successful outcome.

We built a quarter-million mile space highway, paved by one decision, one choice, and one innovation at a time—repeated constantly over almost four days to bring the crew safely home.17

| In our time, when our forward direction is uncertain, one detects fin de siècle nostalgia in all this attention, as though Apollo’s “not because they are easy but because they are hard” spirit is worn out. |

Apollo 13 survived because the flight controllers recognized the errors in their history and quarantined them. Any hardware system, any expectation, plan, or assumption in their thinking that could have been tainted by “facts” was isolated. The new fact-based path, Lunney said, “guided the crippled ship back to planet Earth, where people from all continents were bonded in support of these three explorers-in-peril. It was an inspiring and emotional feeling, reminding us once again of our common humanity. I have always been so very proud to have been part of this Apollo 13 team, delivering our best when it was really needed.”18 (The author’s original wording here was “the new fact-based trajectory.” Jerry Bostick responded, “The use of ‘trajectory’ here still bothers me. I think I know what you mean, but here, I would much prefer ‘path’.)19

The MOCR’s character made the difference. Our best, as Lunney put it, started with rigorous integrity. It saved the mission.

Books and stairs: opportunities and hazards

Popular interest in space exploration is high, with global audiences for Gravity and Cosmos. Live from Space (National Geographic) made television history in the US and Live from Space: Lap of the Planet did the same in the UK. Space-themed programs recently aired or in development include Halle Berry in Extant (CBS), Astronaut Wives Club (ABC), and Ascension (SyFy). Mission Control was planned to be a sitcom based in 1960s NASA, but was canceled recently by NBC before its first episode aired. (See “Gravity’s rainbow,” The Space Review, November 10, 2014).

It might be distressing to see the golden age of American ingenuity and space travel in the rendered in the tone of Ron Burgundy, but after all, lampooning has always been part of space culture. Space Age America consumed José Jimenez, I Dream of Jeannie, and Lost in Space along with the real thing. Von Braun himself and the Mercury Seven took part in, and profited by, making space human and accessible—personal and fun—for the public. In those days, though, optimism and Cold War fear fueled the interest. In our time, when our forward direction is uncertain, one detects fin de siècle nostalgia in all this attention, as though Apollo’s “not because they are easy but because they are hard”21 spirit is worn out.

Dave Scott’s hand controller from Falcon sold at auction in May 2014, reportedly to an anonymous European buyer, for over $498,011,22 not counting the buyer’s premium. That being a new record for space memorabilia, London-based Paul Fraser Collectibles reminded investors that “most of the memorabilia from NASA's early missions and the Apollo flights is safely tucked away in the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum and will not be up for sale any time soon. Disappointing, I know. But it’s great news for those of us that already own NASA collectibles.”23 Auction houses see disappointment, frustration, and impatience like Walter McDougall’s as good market indicators. They are optimistic about the long-term value of Apollo artifacts for the same reason they advise buying a Van Gogh: scarcity. Phenomena like this happen very rarely, maybe just once.

It seems the auction houses have good reason to give this advice. “This is the point. One technology doesn't replace another, it complements. Books are no more threatened by Kindle than stairs by elevators.” That is a tweet from Stephen Fry, whose Twitter page bio describes him as, “British Actor, Writer, Lord of Dance, Prince of Swimwear & Blogger.” One wonders if anyone who retweeted, favorited, and otherwise repeated it considered that the point is not that Kindle or elevators “threaten” books or stairs. It is that they threaten interest in using books or stairs.

Gene Kranz said,

[Y]ou might point out that during Apollo we had a room in the corner of the MOCR that was available to the live press… during missions they could observe the team, listen to all comm, etc…we had a very competent, professional and trusted media.24

Jerry Bostick remembers:

We had a lot of news reporters hanging around in the early days. Some were pretty good and some were pretty bad. My favorite was Roy Neal of NBC News. He called and talked with most of us before each flight. He even came over and sat by me for a full day of sims just to educate himself. There were some who were not that diligent.25

So the challenge of rigorous space reporting is not a new one. However, today’s scarcity of Roy Neals is compounded by the extinction of the old outlets that employed them. The three-network hierarchical media that chronicled the Apollo era is history itself. With centrally-managed newspapers and magazines vanishing, with traditional archives and repositories evolving and delocalizing, there is unprecedented turmoil in the process of publishing; and if today’s stringers, freelancers and self-declared historians do not care to imitate the rigor of Roy Neal in the MOCR, then they can just take the elevator and ignore the stairs.

| Apollo happened in a very different media environment, one with far fewer opportunities for renegades and entrepreneurs. Nothing in the emerging media is inherently compromising to fastidious historiography, but nothing in them requires anything like the pitiless peer review of the MOCR debriefings. |

Google “Apollo history blogs” at this writing, the search gets 9,660,000 results in 0.38 seconds, so there is some work involved in understanding which ones might earn Kranz’s mantle of “very competent, professional and trusted media.” Then again, the “history” that is produced professionally might be even worse. Fox’s Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon?, aired twice in 2001 on the strength of heavy promotion, and said no, it was all faked.26 SyFy Channel’s salute to Apollo 11’s 45th anniversary was Aliens on the Moon: The Truth Exposed.27

As the 50th anniversaries of the lunar missions approach, and (we hope) bring with them a renaissance in public interest, new technologies offer space historians unprecedented possibilities for collaboration, access to records, and creativity in media. Dr. Seth Denbo, Director of Scholarly Communication and Digital Initiatives at the American Historical Association, described the opportunity: “The kinds of interchanges that the Web allows, the kinds of scholarly communities that it permits, are much easier to build now than they’ve ever been,” he said. “Being able to interact and share has real benefits; and the availability of sources has changed the historian’s world. Now you can access libraries and repositories that formerly required travel. That’s a tremendous change.”

“That said,” he continued, “there is much more potential for shoddy scholarship, unevaluated scholarship, to get out there into the world, and it’s up to professional historians to help educate the world about how to read history, and that way we have a chance to influence how people understand what they’re reading, as much as possible.”28 Denbo and colleagues on the AHA’s Ad Hoc Committee on Professional Evaluation of Digital Scholarship by Historians have undertaken to “address the professional evaluation of digital scholarship.” The goal “is not only to address a ‘problem’ (evaluation of a growing body of scholarship), but to encourage innovation. By producing guidelines and criteria that can be used to evaluate digital projects, this committee will help the discipline to better recognize, understand, and appreciate these new forms of scholarship.”29 Professional historians are behind the technology: “The committee is focused on the issues around professional reputation when it comes to doing scholarly work on the web or scholarly digital work in history,” Denbo said, “because despite twenty years of digital scholarship, professional historians working in the academy really still build their reputations by writing print journal articles and books. We need to broaden that. That’s not to diminish the importance of books and articles; they’re the best way of doing things in many fields and topics—but there are many projects where you can do incredible work by building interactive media and make real contributions to scholarship and we’re helping to give that a better place in the making of professional reputations.”30

Apollo happened in a very different media environment, one with far fewer opportunities for renegades and entrepreneurs. Nothing in the emerging media is inherently compromising to fastidious historiography, but nothing in them requires anything like the pitiless peer review of the MOCR debriefings. Bluffing is not penalized, assuming anybody detects it in the first place. Quality is measured by the size of the audience. For all the promise of this coverage, the option of diligence, the absence of mutual accountability, and an undiscriminating viewership all just make it that much easier for sloppy purveyors to get history wrong with terrific production values; and worse, for readers and viewers unknowingly to follow the corrupted trajectory. The result is a win for verisimilitude, sometimes with the very duty of authenticity abandoned like outmoded hardware. The risk is an historiographical version of the Kessler syndrome, with incorrect information propagating more of the same like orbital debris:31 imagine having been there in the Trench in Mission Control during Apollo 8, and 40 years later, seeing a documentary wherein the narrator intones, “Apollo 8 is shooting blindly for the moon. Computers calculate their trajectory. If the numbers are off by even a little they’ll either crash into the lunar surface or miss the moon completely and just keep going.”32 Dramatic, fun, and wrong. There was no “shooting blindly.”Jerry Bostick and his colleagues calculated the trajectory. The numbers were never “off.”

Do new media require historians to make factuality just an option? Can space historians study the rigor, linearity, discipline, and mutual accountability enforced in the MOCR and do space history justice while compromising the MOCR’s methods? Here at the handover, formal governance is absent, and informal governance happens only if the people involved enforce it. Some indispensable space resources on the Web have done that.33 Other sites, less carefully monitored, have been vulnerable to contributors whose dishonesty has required the removal of plagiarized materials,34 and given how easy it is to steal and reprocess material, plagiary is likely to be common. Others misrepresent deliberately to the point where we do not lose the sources—they lose us. “Twists and distortions do take place, and I don't know how to stop them, except not to give any interviews,” Edgar Mitchell told NBC News in an email. “Any help is appreciated.”35 Sy Liebergot tells a story about the producer of a television show who wanted to cover Apollo 13. The program was magazine-style with segments, and they wanted to use one to tell the thrilling saga of peril and heroism before the commercial break. Liebergot asked the producer, “You’re really going to do this mission in twelve minutes?” “Sure,” the producer said. “We’re masters of trivialization.”36

Endnotes

- “After various lines and wires were disconnected and bolts which hold the shelf in the SM were removed, a fixture suspended from a crane was placed under the shelf and used to lift the shelf and extract it from bay 4. One shelf bolt was mistakenly left in place during the initial attempt to remove the shelf; and as a consequence, after the front of the shelf was raised about 2-inches, the fixture broke, allowing the shelf to drop back into place. Photographs of the underside of the fuel cell shelf in SM 106 indicate that the closeout cap on the dome of Oxygen Tank No. 2 may have struck the underside of that shelf during this incident. At the time, however, it was believed that the oxygen shelf had simply dropped back into place and an analysis was performed to calculate the forces resulting from a drop of 2 inches. It now seems likely that the shelf was first accelerated upward and then dropped.” REPORT OF APOLLO 13 REVIEW BOARD. NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION. APOLLO 13 REVIEW BOARD. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Washington, D.C. 20546. June 15, 1970. http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/lunar/apollo_13_review_board.txt. Accessed July 21, 2014.

- Edgar M. Cortright, et al, REPORT OF APOLLO 13 REVIEW BOARD. June 15, 1970. http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/lunar/apollo_13_review_board.txt. Accessed May 25, 2014.

- National Space Science Data Center. “Detailed Chronology of Events Surrounding the Apollo 13 accident. Events from 2.5 minutes before the accident to about 5 minutes after.” http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/lunar/ap13chrono.html. Accessed May 26, 2014.

- Stephen Cass, “Apollo 13, We Have a Solution.” IEEE SPECTRUM. Posted 1 Apr 2005. http://spectrum.ieee.org/aerospace/space-flight/apollo-13-we-have-a-solution. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- Fred W. Haise, interview by the author, November 4, 2011.

- Personal email to the author from Gene Kranz, July 5, 2014.

- Charles Murray and Catherine Bly Cox. Apollo. The Race to the Moon. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1989. p. 397.

- Sy Liebergot with David M. Harland Apollo EECOM: Journey of a Lifetime. Burlington, Ontario, Canada: Apogee Books: 2003. p. 140.

- Sy Liebergot with David M. Harland Apollo EECOM: Journey of a Lifetime. Burlington, Ontario, Canada: Apogee Books: 2003. p. 140.

- Sy Liebergot with David M. Harland Apollo EECOM: Journey of a Lifetime. Burlington, Ontario, Canada: Apogee Books: 2003. p. 144.

- Sy Liebergot with David M. Harland Apollo EECOM: Journey of a Lifetime. Burlington, Ontario, Canada: Apogee Books: 2003. p. 138-151.

- Steven Lloyd Wilson, “Original Audio of Apollo 13 Incident, in Real Time.” January 6, 2014. http://www.pajiba.com/miscellaneous/original-audio-of-apollo-13-incident-in-real-time.php. Accessed June 2, 2014.

- An early draft of this article said, “Gene Kranz disabused everyone involved from continuing along the wrong path.” Jerry Bostick commented, “Not sure how sophisticated the Quest readers are, but you use some pretty fancy words that may not be fully understood by some. Us steely eyed space scientists use pretty basic language.” Jerry Bostick, personal email to the author. July 9, 2014.

- Jim Lovell & Jeffrey Kluger, Lost Moon. The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1994. p. 103.

- Personal email to the author from Gene Kranz, July 5, 2014.

- Sy Liebergot with David M. Harland Apollo EECOM: Journey of a Lifetime. Burlington, Ontario, Canada: Apogee Books: 2003. p. 148.

- “APOLLO XIII.” Glynn S. Lunney. NASA History Portal. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/LunneyGS/Apollo13.htm. Accessed May 27, 2014.

- “APOLLO XIII.” Glynn S. Lunney. NASA History Portal. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/LunneyGS/Apollo13.htm. Accessed May 27, 2014.

- Jerry Bostick, personal email to the author. July 9, 2014.

- GRIN-Great Images in NASA. http://dayton.hq.nasa.gov/IMAGES/LARGE/GPN-2000-001313.jpg. Accessed June 20, 2014.

- John F. Kennedy Moon Speech - Rice Stadium September 12, 1962. http://er.jsc.nasa.gov/seh/ricetalk.htm. Accessed June 7, 2014.

- Lorenzo Ferrigno and Larry Frum, CNN, “Artifacts from Apollo missions sell at out-of-this-world auction.” updated 8:30 PM EDT, Fri May 23, 2014. http://www.cnn.com/2014/05/23/us/apollo-space-auction/. Accessed May 28, 2014.

- Paul Fraser Collectibles, “If I could give you one tip for a profitable collection...”. http://www.paulfrasercollectibles.com/News/Space-%26-Aviation/If-I-could-give-you-one-tip-for-a-profitable-collection.../17208.page?catid=79. Accessed May 28, 2014.

- Personal email to the author from Gene Kranz, July 5, 2014.

- Jerry Bostick, interview with the author. May 14, 2014.

- Phil Plait, “Fox TV and the Apollo Moon Hoax.” BadAstronomy.com. http://www.badastronomy.com/bad/tv/foxapollo.html. Accessed May 30, 2014.

- Jason McClellan, “SyFy documentary to reveal the truth about aliens on the Moon.” July 8, 2014, http://www.openminds.tv/syfy-documentary-reveal-truth-aliens-on-the-moon/28793. Accessed July 23, 2014.

- Dr. Seth Denbo, Ph.D., Director of Scholarly Communication and Digital Initiatives, American Historical Association. Interview with the author. June 16, 2014.

- James Grossman and Seth Denbo, “Making Something Out of Bupkis: The AHA’s Ad Hoc Committee on Professional Evaluation of Digital Scholarship.” Perspectives on History, the Magazine of the American Historical Association. February 2014. http://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/february-2014/making-something-out-of-bupkis-the-aha%E2%80%99s-ad-hoc-committee-on-professional-evaluation-of-digital-scholarship. Accessed June 6, 2014.

- Dr. Seth Denbo, Ph.D., Director of Scholarly Communication and Digital Initiatives, American Historical Association. Interview with the author. June 16, 2014.

- Steve Olson, “The Danger of Space Junk.” The Atlantic. Jul 1 1998 http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1998/07/the-danger-of-space-junk/306691/. Accessed June 23, 2014.

- Dangerous Films, When We Left Earth: The NASA Missions. Discovery Chanel, 2008. (2008 TV Mini-Series). http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1233514/?ref_=ttfc_fc_tt. Accessed June 17, 2014.

- We can thank Robert Pearlman of collectSPACE, Eric Jones of the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal, Jeff Foust of The Space Review, and other scholars and journalists who have set a standard for thoroughness, rectitude and scholarship.

- Robert Kennedy and Dwayne Day, “Plagiarism in several space history articles.” The Space Review. November 4, 2013. http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2394/1. Accessed June 13, 2014.

- Alan Boyle “'Aliens on the Moon' TV Show Adds Weird UFO Twists to Apollo Tales”. NBCNews. July 18th 2014. http://www.nbcnews.com/science/space/aliens-moon-tv-show-adds-weird-ufo-twists-apollo-tales-n159806. Accessed July 21, 2014.