Old myths never die, they just (sorta) fade awayby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Compared to the intense repetition in January and February, a review of general publications indicates that the $1-trillion cost figure has appeared only a handful of times since June. |

Shortly before Bush made his announcement, the story that NASA was about to embark on a bold new exploration effort leaked to the media. The Associated Press wire service ran a story on the plan and included the claim that unnamed experts estimated that it could cost $1 trillion. Many newspapers often rewrite AP stories and shorter versions of this article appeared in dozens of newspapers over the next week. Indeed, it is impossible to determine just how many newspapers carried the story. In addition, other reporters repeated the claim, occasionally citing the AP as a source, or quoted an “expert” (not often defined), or even politicians who had clearly gotten the figure from the AP story. The AP claim was also repeated numerous times on radio and television stations. A conservative estimate is that the $1 trillion figure appeared in multiple dozens of newspapers and other media sources during January 2004. (See “Whispers in the echo chamber: Why the media says the space plan costs a trillion dollars”, The Space Review, March 22, 2004.)

But compared to this intense repetition in January and February, a review of general publications such as newspapers archived in the Lexis/Nexus media database indicates that the $1-trillion cost figure has appeared only a handful of times since June. The Times of London repeated the claim in a column in early November. So did the Toronto Star in an opinion column in August. (A common theme among British and Canadian writers seems to be that the Vision for Space Exploration is yet another example of the ways that Americans waste huge amounts of money on unimportant projects.) New York Times science writer Kenneth Chang also tossed out the bogus claim that a Mars mission would cost $1 trillion. An Associated Press article in June made the same claim—probably because that AP writer was merely relying upon the earlier AP writer—and it was repeated in a Roanoke Times and World News editorial a few days later. But that is just about it: only about five examples since June.

There have been far fewer stories about the Vision for Space Exploration in the past six months than there were in the month of its announcement, and this certainly explains why the myth is less repeated—fewer stories result in fewer mistakes. Clearly that is not the only factor at work, though. To be fair to the media as a whole, one must not simply count examples of them getting the story wrong, but should also consider the examples of them getting it right when they could have gotten it wrong. There are a number of examples of the press accurately reporting about the costs of the Vision in the past six months, although certainly far less than the large number of inaccurate stories back in January.

| Unfortunately, the nonpartisan CBO study did not get much attention when it was produced, but it is now in the public domain and there is absolutely no excuse for a reporter to ignore it. |

For example, the December issue of The American Enterprise magazine contains an excellent series of interviews with three “space legends” that quotes NASA’s $100 billion cost estimate for the Vision. (However, the magazine also printed an article titled “The Sober Realities of Manned Space Flight,” that is filled with errors and false assertions about space costs.) National Public Radio did a short story a few months ago concerning a Congressional Budget Office report on the likely costs of the Vision that accurately portrayed what was in that report, although the gist of the story was that NASA is dramatically underestimating the costs.

Unfortunately, the nonpartisan CBO study did not get much attention when it was produced, but it is now in the public domain and there is absolutely no excuse for a reporter to ignore it. The CBO study (for which this writer served as an unpaid consultant and reviewer) noted that NASA projects typically cost about 45% more than the agency’s initial estimates, meaning that the entire Vision for Space Exploration could cost almost $150 billion over the next fifteen years. Neither the NASA figure nor the CBO figure are likely to be entirely accurate, but they have real accounting principles and justifications to support them, unlike the $1-trillion figure, which was essentially invented by a lazy reporter.

So it is safe to say that the $1-trillion cost estimate myth has faded. It is not, however, completely eradicated. It still seems to appear most often in opinion pieces, like editorials, as opposed to “hard news” articles (the New York Times article by Chang being the one glaring exception). But it is no longer the default figure for the cost of space exploration.

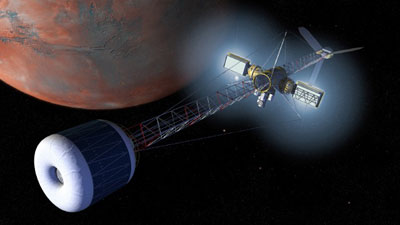

The other myth, that Bush’s plan involves sending humans to Mars, seems to have a little more staying power. But this is more a subjective assessment than a qualitative one. A Lexis/Nexus search under the terms “humans” and “Mars” turns up more articles where both opinion writers and even reporters claim that the Vision is about sending humans to Mars. But unlike the cost estimate, in these cases it more often comes down to a matter of emphasis than a statement of fact.

As currently established, the Vision includes few projects devoted to human missions to Mars. Virtually all of the technology development for human exploration missions is devoted to the lunar goal. Yet reporters often mention the lunar and Mars goals as if they are equally represented in the current plans. At the very least the writers will usually include a line about “eventual missions to Mars,” without explaining that the amount of money devoted to this “eventual” possibility in the five-year budget plan is currently almost nothing at all.

Opinion writers have been more willing to claim that the Bush plan is a “humans to Mars” effort. Bronwyn Lance Chester, a columnist for the Hampton Roads Virginian-Pilot, called the Vision “Project Martian Madness” in a column last week. Other opinion writers made similar claims before the presidential election, usually trying to score partisan points against the Bush administration.

The “humans to Mars” myth seems to be putting up more of a struggle instead of going peacefully into the good night. But unlike the trillion-dollar myth, this myth may be perpetuated for reasons other than laziness and partisan sniping. One reason is that Mars exploration is currently ongoing and therefore in the public eye in a way that lunar exploration is not. People see images of the Spirit and Opportunity rovers on Mars and assume that NASA is more focused on Mars than the Moon, including human exploration.

| The “humans to Mars” myth seems to be putting up more of a struggle instead of going peacefully into the good night. But unlike the trillion-dollar myth, this myth may be perpetuated for reasons other than laziness and partisan sniping. |

Another reason may be romantic. Mars has long captured the imagination in ways that the Moon has not, and reporters and opinion writers may simply be drawn to it because of its powerful symbolism and appeal. Many people think that the Moon is boring. “Humans to Mars” is thus a sort of cultural shorthand both for the folly of space exploration and the romance of it.

Finally, some credit for the fading of these myths should be given to both sides in the recent political campaign. The Bush administration clearly chose to remove the Vision for Space Exploration from the public discussion, probably because the White House took such a beating on it back in January. But the Kerry campaign also did not make a big issue out of the Vision, nor falsely exaggerate its costs or its goals. Kerry spokespersons never claimed that Bush planned on spending hundreds of billions putting humans on Mars. Instead, what little discussion there was of the Vision concerned the overall “balance” of programs at NASA, such as exploration versus earth science and aeronautics, a legitimate subject that even the Republican Congress has discussed. (See “The great (well, ok) space debate”, The Space Review, October 18, 2004.) The myths persist in spite of the presidential campaign, not because of it.

Small victories, but victories nonetheless.