The stars, my inspirationby Dwayne Day

|

| Inspiration requires receptivity and predisposition, but also activity. It is not really inspiration if the recipient does nothing but feel good—it is only appreciation, not motivation. |

Now, another electronic musician Jonn Serrie has released a new album, The Sentinel, and his inspiration illuminates the iterative and repetitive nature of inspiration, and how an inspirational event or subject can echo in a person’s mind over a lifetime.

Serrie has been making music for four decades now, using synthesizers and other electronic instruments. One of his primary outputs over the years has been composing soundtracks for planetarium shows—music for space, inspired by space.

On his website, Serrie explains the origin of his new album:

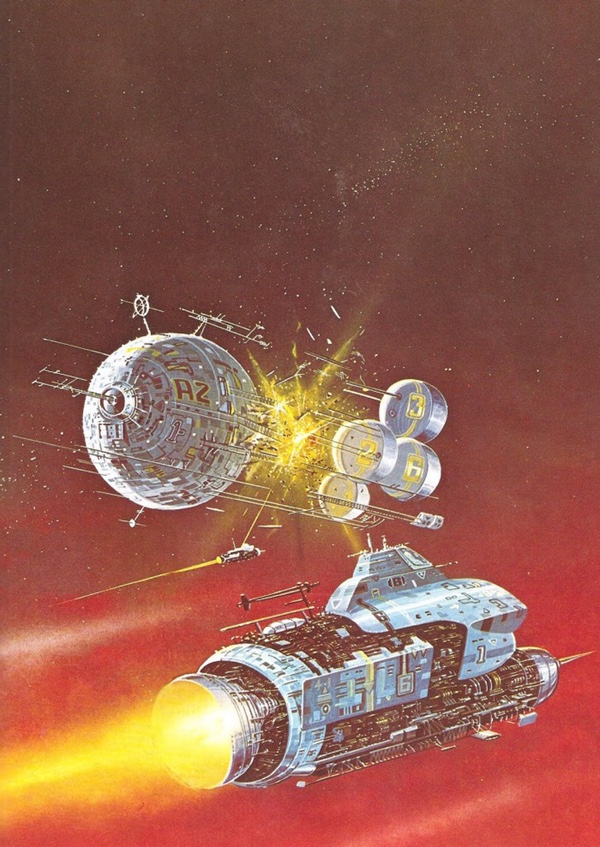

“In the late 70’s when I was beginning my career in the creation and production of professional space music for the planetarium industry, I came across Stewart Cowley's book series that told stories of the Terran Trade Authority through prose and space art,” Serrie writes.

“The work used to support the stories came from the portfolios of some of the finest space artists in the world. These books, Spacecraft, Spacewreck and Great Space Battles, became a personal Bible of inspiration, musical vision and synthesizer programming techniques for planetarium show production and space music album concepts for many years. To this day, I still use them in that fashion.”

“The Sentinel represents a virtual reality journey, going deep into my imagination and musical universes as I create audio chapters of space music that the listener can experience firsthand. In this journey, you are The Sentinel, you are on the command bridge, you are wearing the spacesuit, it is your universe, all told through imagination and the superb influence of these three great books.”

As Serrie notes, the books also influenced others who encountered them in the latter 1970s such as James Cameron and special effects producer Douglas Trumbull. Homeworld, a popular strategy-based video game that debuted in 1999, clearly took many cues from the original books. And Cowley’s books were themselves obviously inspired by space artists, notably Chris Foss, whose colorful paintings of starships inspired numerous people in the 1970s. Foss worked with noted futurist illustrator Ron Cobb to develop the look of the 1979 movie Alien, and the two had designed the brooding (and very non-colorful) ship Nostromo. The Nostromo, and the beast that inhabited it, certainly inspired nightmares.

Ambient musicians are frequently inspired by nature and abstract and scientific subjects. Steve Roach has composed music about deserts, or the primordial origins of life. Robert Rich has composed an album about the Earth after humanity is gone. As for Serrie, he has said that his “goal is to dissolve the veil between source and destination, so my audience feels the music the way I do and I feel the music the way they do.”

| Anybody who claims that they were inspired by Star Trek probably had a reason that they watched the show in the first place. Something drew them to it. |

Listening to The Sentinel, it is obvious that Serrie has accomplished his goal. The pieces have titles such as “The Sentinel,” “Centauri Arrival,” “The Veils of Beta Pavlonis,” and “Starship Destiny Homeward.” If you know the source material, know the paintings in the books, Serrie’s music seems perfectly written for them, for a daydream time where giant spaceships travel to exotic worlds for trade, encounter stellar mysteries, and occasionally battle each other. A musician who, four decades ago, was inspired to write soundtracks for planetariums by books he had seen, has now written music to accompany those books, to create a soundtrack for the words and the art. Inspiration both vast and now specific, an echo decades after the original tone.

The artwork of the “Terran Trade Authority” science fiction series helped inspire Serrie, decades later. |

Inspiration, or rationalization?

Inspiration, of course, has other definitions and conceptualizations. People may hear a heroic tale, or read a passage in the Bible, and take inspiration from that. But in that sense inspiration is really only a positive feeling, not something that results in action. Looking at a poster of a kitten hanging from a clothesline with the words “Hang in there, baby!” might provide the little extra kick to get somebody to go to work in the morning, but it’s not really the kind of inspiration that we imagine can be recorded or measured. It’s not a life-changing event.

In order for someone to be inspired they must first be receptive and predisposed. Millions of school children are trotted through museums every year, but most leave indifferent to what they have seen, uninspired. You can see this every day in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, where a few are fascinated by the aircraft and spacecraft, but most do not care one bit and are only in pursuit of their classmates, or mischief. Yet those children uninspired by the spaceships may be inspired by other things. Perhaps some of them will hear an orchestral performance and be inspired to learn to play the violin, or others will see a baseball game and be inspired to take up the sport. If the space museum does not inspire them, maybe the art museum will. This is one of the reasons why teachers take students to museums.

Anybody who claims that they were inspired by Star Trek probably had a reason that they watched the show in the first place. Something drew them to it. Maybe the inspiration started with something else, something vague and unknowable, and it refined itself gradually. Many people may start with this abstract feeling or inclination, but something real that they encounter allows them to visualize it better in their head and to apply it to their own life. Maybe they realize that the thing that they enjoy can actually be a career path, or a discipline to study. Or perhaps they see a piece of fictional hardware—like Mister Spock’s tricorder—and it solidifies in their mind’s eye into something that they will try to make real. The stimulus provides motivation not just in general (i.e. “go to work”), but in a specific direction (“build this thing”). Even then, not all inspiration is equal: there is a difference between being inspired to study classical guitar… and taking up air guitar.

A specific, singular stimulus may not be necessary for everyone. Motivation, interest, and action can be much more organic in origin—a child who grows up with a father who is always fixing cars may become a mechanic. A girl whose sisters love to play soccer may also grow to love the sport. They may not be able to remember any specific event or moment when their hobbies or career choices suddenly clicked into place for them. And some people are inspired not by a thing, but by a person who pays attention to them and provides them with the self-confidence that they can do the things they want to do. Teachers and mentors can provide inspiration too. A love interest can inspire someone to become a better person themselves, to quit smoking, lose weight, dress better, all to be deserving of the object of their desire.

A physicist friend of mine who was inspired by science fiction movies like 2001: A Space Odyssey but does not work in the space sciences has noted that space often serves as the gateway to scientists in general, including many, like him, who do not always go into the space sciences. He suggests that maybe it is because space is so visual that it allows a young person to become fascinated with things like physics, or even other sciences like chemistry, that otherwise are difficult to conceive of visually.

| What is it about spaceflight that gives it such powerful ability to inspire, even if we might be rationalizing specific moments or events or people for our attraction to space? |

Another physicist who does work in the space sciences has suggested that perhaps this is the wrong way to look at inspiration and what triggers it. Perhaps we are the conscious witnesses of unconscious processes, and we construct rational explanations for our choices by pointing to specific real-world examples, like Neil Armstrong walking on the Moon or Montgomery Scott fixing the Enterprise’s transporter. We don’t recognize what is really occurring in our own minds, but think that we do. We are rationalizing after the fact.

But still… why spaceflight? What is it about spaceflight that gives it such powerful ability to inspire, even if we might be rationalizing specific moments or events or people for our attraction to space? Because most people today live in cities, they are disconnected from the night sky and less likely to be inspired by it. Spaceflight, however, remains somewhat mysterious, and still has a mystical, spiritual allure. It is generally inaccessible. It challenges survival, and it makes heroes. We call space the heavens, a term we do not use for the bottom of the ocean or a distant mountain range. Spaceflight thus represents a form of spiritualism, perhaps one that is more acceptable to people who have problems with other forms of spirituality. Jonn Serrie has long composed music for planetariums, which bring the night sky to people who may not be able to see it in a light polluted world. With The Sentinel, he continues that quest. And—who knows?—maybe The Sentinel will inspire somebody else to make more art, to compose their own music, or even to travel into space.