Space alternate history before For All Mankind: Stephen Baxter’s NASA trilogyby Simon Bradshaw

|

| Few have returned more consistently to the topic than British science fiction author Stephen Baxter. |

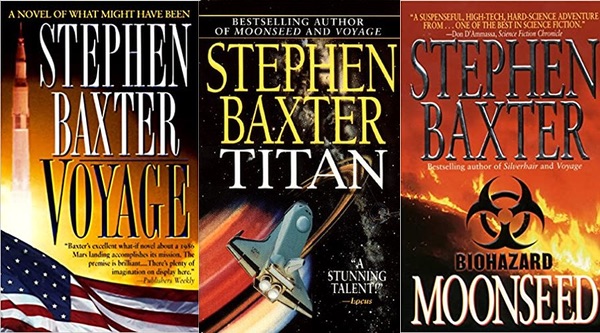

Voyage (HarperCollins, 1996), Titan (HarperCollins, 1997) and Moonseed (HarperCollins, 1998) are not, in any conventional sense, a trilogy; each stands alone, in a separate continuity. They do not even share the relationship of Baxter’s subsequent “Manifold” series, which recycles the same characters through three very different parallel universes. But they nonetheless share a strong thematic link that has led to their collectively being termed Baxter’s “NASA Trilogy”. Each novel, to a significant extent, addresses the United States’ relationship with space exploration, and in particular its own space program.

That said, each book takes a distinct approach to this question, and Moonseed does so in a manner different enough from either Voyage or Titan that had the three books not been published in sequence it might well not be classed with them. Moonseed is many respects closer to later Baxter novels such as Flood (Gollancz, 2008), with its ensemble cast and theme of global disaster. Nonetheless, a major plot element is a space mission put together by NASA under pressure of a single-minded goal and at the direction of a clique of maverick scientists and engineers. In this respect, it shares a common plot threat with both Voyage and Titan, and it is clear reading them together that much of the research—both technical and, in terms of NASA, cultural—for Voyage was carried through into the subsequent books. As this article concentrates on Baxter as a writer about the US space program, though, it will concentrate primarily on that aspect of Moonseed rather than the book’s more general “disaster novel” theme.

To consider Voyage first, it is itself distinct from the other two books in the NASA Trilogy in a fundamental way. Both Titan and Moonseed are conventional near-future SF; Titan is explicitly set in the period from 2004 to the mid-2010s (with a coda in the deep future) while Moonseed is set a few years in the future of its 1998 writing date. Voyage is, by contrast, an alternate history, running from 1969 to 1986. But whereas many alternate histories depict alternative wars, leaders or political systems, Voyage has a very specific counterfactual: an alternative post-Apollo US space program, one that goes onwards to Mars.

The history of space exploration seems to be a particularly fruitful ground for counterfactuals, even outside fiction. Space history enthusiasts have a fascination with “what-ifs”, manifesting itself in forms ranging from discussion on Internet discussion groups and web forums[2] to entire books on unflown space missions.[3] There are two significant factors behind this. First, behind every flown space mission or rocket design there stand the ghosts of a dozen studies or proposals that never got selected or developed. There is no shortage of contractor studies or NASA proposals to inspire speculation as to how the space program might have unfolded differently. Second, the time-pressured, disaster-prone nature of the Space Race made it particularly open to the whims of fate. It is well-documented, for instance, how Apollo 8 was rescheduled from a Lunar Module test flight in Earth orbit to a dramatic Christmas voyage around the Moon, in response to intelligence that the Soviet Union was planning its own circumlunar mission. Similarly, a series of launch failures doomed the USSR’s counterpart to the Saturn V, the N-1, and the Soviet lunar landing project with it.

| Baxter is not satisfied with asking what might have happened if NASA had decided to go onwards to Mars. He wants to justify that change. |

These factors might explain why the might-have-beens of spaceflight are of such interest to space history enthusiasts. But why are so many science fiction writers moved to go beyond counterfactuals into alternate history? As noted, Baxter is by no means the only author to have taken this route, but what distinguishes him is the frequency with which he has returned to this particular theme. In an article for Vector[4] he notes that in addition to Voyage he has written several short stories exploring variations upon the theme.[5] Reviewing some of the other “alt.space” fiction mentioned earlier, he discerned in some writers a desire to address the disappointment of a space program that seemed to have drawn back from its promise of exploring new worlds into a frustratingly humdrum round of commercial and military missions to low orbit. But Baxter noted his own dissatisfaction with such a simplistic approach; for him, to interpret the 1960s space race as the start of a visionary program of exploration was to badly misread it, and any credible alternate history in which it went further than it did in reality had to confront this:

I had come to believe that the Apollo project was fundamentally crazy… To reach outwards to Mars I was going to have to find ways to extend that craziness.[6]

On the face of it, the historical point of departure in Voyage is in the immediate aftermath of Apollo 11, as NASA management considers options to present to Nixon as to how to follow up the Moon landing. But he notes, Baxter is not satisfied with asking what might have happened if NASA had decided to go onwards to Mars. He wants to justify that change, and does so by revealing that the world of Voyage departed from ours some six years before—to be precise, on the 22nd of November 1963:

And then familiar tones – that oddly clipped Bostonian accent – sounded in his headset, and Muldoon [Baxter’s fictional stand-in for Buzz Aldrin] felt a response rising within him, a thrill deep and atavistic.

“Hello, gentlemen. How are you today? I won’t take up your precious time on the Moon. I just want to quote to you what I said to Congress on May 25, 1961 – just eight short years ago…”

For here John F. Kennedy survived Dallas, although Jackie did not, and while crippled remains a powerful influence on US politics and the space program in particular. Many space historians consider that respect for Kennedy’s legacy did much to ensure the survival of the Apollo program in the face of the fatal Apollo 1 fire and the budgetary pressures of the Vietnam War. If he had still been alive, suggests Baxter, especially if near-sanctified by surviving an assassination attempt that had left him a widower, how much harder still would it be to resist his vision? And so he has Kennedy publicly urge America onward to Mars, a push that tips the balance away from the development of the Space Shuttle that NASA in reality settled on.

Indeed, to a student of Apollo, Baxter’s counterfactual is fascinatingly subtle. Had he simply posited that Kennedy was not assassinated, then he would have had to contrive a much wider alternate history, and in particular grappled with the thorny question of how Kennedy would have handled the growing war in Vietnam. But more specifically, and more relevant to the novel, Baxter would also have had to show how Apollo itself would have continued under Kennedy. As space historian Dwayne Day has explained, there is plenty of evidence that Kennedy’s motivations for proclaiming his goal of a Moon landing were more complex than is often assumed, and formed part of a wider geopolitical game with the Soviet leadership.[7] A second-term President Kennedy might, Day notes, have reviewed his own plans in light of both wider political issues and the USSR’s own space program. To take an extreme view, perhaps we live in the unlikely timeline where Kennedy’s death meant that Apollo continued with a blind momentum that his successors lacked the will to divert. But what Baxter does is contrive the same effect while still leaving Kennedy available as a figure with influence on later space policy—perhaps even pushing the US still further onwards.

Taking this premise, Baxter goes on to extrapolate as rigorously as possible how NASA might have sought to fulfill a mandate to land a human on Mars. And, as noted, there was no shortage of material from which he could work; NASA carried out extensive studies throughout the late 1960s on human Mars missions, and Voyage is a painstaking attempt to depict how such plans may have unfolded, including the inevitable setbacks and disasters. Baxter adopts an interesting narrative device in presenting his history: Voyage starts with the launch of Ares, then flashes back to the Apollo 11 landing and the genesis of the mission. From this point the two narrative strands alternate, with the mission unfolding alongside the story of its development. In some respects, this tones down narrative tension: the reader knows, for example, that Natalie York gets a seat on the Ares mission, so her plot arc in the parallel narrative becomes the story of how this happened, not whether it will. But this approach also rewards the attentive reader, who may note that some of the concepts and characters in the earlier narrative are not present in the later one, and will perhaps get an inkling as to why before actually being shown.[8]

| Voyage depicts not only a realistic vision of how NASA might have travelled to Mars by 1986 but also shows the consequences of what Baxter referred to as the “extended craziness” of a narrowly-focused vision of space exploration. |

Baxter adds to the verisimilitude of his imagined history by having it closely reflect episodes and personalities of the real space program; aficionados of Apollo history will recognize characters such as project manager Bert Seger, ex-Peenemünde rocket engineer Hans Udet, and aerospace designer J. K. Lee as barely-disguised avatars of Joe Shea, Arthur Rudolph, and Harrison Storms. As an aside, such “factionalization” raises the question of how far an author should go in adapting real-life events into fictional incidents. On the one hand, it can add realism and authenticity: it is hard to criticize a scene as being unrealistic or inaccurate if it in fact mirrors something that took place in real life. On the other, it can detract from the narrative flow if a reader recognizes the incident on which it was based. Ironically, the very space-obsessed readers most likely to enjoy Voyage are the ones most likely to be familiar with the real incidents and personalities Baxter has adapted. For my part, I am inclined to agree with the late Patrick O’Brian’s justification of his very similar approach to writing his naval fiction:

My point is that the admirable men of those times … from whom I have in some degree compounded my characters, are best celebrated in their own splendid actions rather than in imaginary contests; that authenticity is a jewel; and that the echo of their words has an abiding value.[9]

Returning to Voyage, however, it depicts not only a realistic vision of how NASA might have travelled to Mars by 1986 but also shows the consequences of what Baxter referred to as the “extended craziness” of a narrowly-focused vision of space exploration. Although the Ares mission succeeds and NASA has another crowning triumph, it is explicitly noted that it has been at a considerable cost to wider space exploration. Noting how 1960s lunar probes had their missions progressively bent from scientific exploration to path-finding for Apollo, Voyage depicts a 1980s NASA that has thrown its all into putting three people onto Mars, but which in doing so curtailed its lunar program even more brutally than was the case in our timeline[10] and which knows little of the outer planets, missions such as Voyager having been sacrificed to the Mars budget. With no funding for further missions, no Space Shuttle, and no wider goals in sight, Voyage ends with a NASA that has realized another stunning achievement—a human standing on the dried-out riverbeds of Mangala Vallis—but nowhere to go and nothing to do afterwards. A post-Apollo Mars mission, Baxter suggests, would have been glorious, but a glorious dead end.

Even so, in Voyage Baxter presents NASA in a very positive light. The Ares mission becomes a symbol of national unity; the chronic infighting between NASA centers nonetheless gives birth to a successful mission plan; even the terrible cost not only in lives lost but lives suborned to decade-long urgent projects is presented as an inevitable cost of the road to the stars. Whatever Baxter might think of the craziness of huge-budget, single-goal space projects, his admiration for the way in which NASA tackled them in the Apollo era shines through Voyage.

It is a very different tone which permeates Titan.

Many science fiction writers may wish to be remembered as having been prophetic. As far as Titan goes, Baxter may well rue any such reputation it garners him. Indeed, given the hostility Titan attracted in some quarters on release—one noted online reviewer accused it of being so bad that “It would not surprise me if reading that book caused birth defects”[11] —the prophetic reputation it may gather him is that of Cassandra. For this is a book written in 1997 that predicted that the first decades of the new century would feature the loss of the space shuttle Columbia, the shutdown of the shuttle program, human spaceflight by China, and an aggressively right-wing US presidency. None of these were particularly startling predictions on their own; even the shuttle disaster was based on Baxter’s own frank appraisal of NASA’s own safety statistics, and the observation that Columbia was the oldest vehicle in the fleet.[12] Nonetheless, Titan remains a novel that whatever its real or perceived thoughts has the dubious distinction of having held a surprisingly accurate mirror to the period it sought to portray, albeit a very dark one. And “dark” is the right word; the negative reaction Titan aroused may well have been in large part in reaction to Baxter’s bitter cynicism about the corruption of NASA’s dream by short-term politics, not to mention the relentless ordeal he subjects his characters to as they embark on a mission cobbled together from the last relics of the US space program to investigate possible signs of life on the eponymous Saturnian moon.

If Voyage is a hymn to the sometimes-flawed aspirations and achievements of the US civilian space program, Titan at times reads as a diatribe against its military counterpart. (Baxter has himself described Titan as “an angry book.”[13] ) It is worth remembering that the US has had a military space program since before NASA existed; the abortive X-20 spaceplane project began in 1957, nearly a year before NASA’s formation, and the Space Shuttle flew nearly a dozen missions dedicated to military payloads. In 1982, the US Air Force formed its own Space Command, and by the time Baxter was writing Titan this had grown to absorb satellite communications, space launch, and even the US land-based nuclear missile force. Indeed, in 1998 the then Republican Senator for New Hampshire, Bob Smith, called for it to be established as a separate US Space Force and for the US to seize control of what he termed the “permanent frontier”:

…space offers us the prospect of seeing and communicating throughout the world; of defending ourselves, our deployed forces, and our allies; and, if necessary, of inflicting violence…

Control of space is more than a new mission area—it is our moral legacy, our next Manifest Destiny, our chance to create security for centuries to come.[14,15]

Although Senator Smith spoke after Baxter drafted Titan, such sentiments were by no means new or uncommon at the time. Baxter was writing against a background of growing calls in the US for it to extend its seeming global dominance—then, before 9/11, Iraq and Afghanistan, seemingly in its post-Cold War ascendency—into space itself. From such a perspective, a space program that discarded science and exploration in favor of military domination was not unrealistic. In a seeming paradox, the dystopian world of Titan couples this with a progressively more repressive near-theocracy that all but suppresses science; Baxter seems to suggest that American ingenuity and determination can extend to the Orwellian doublethink required to operate military spaceplanes in a culture that officially rejects heliocentric cosmology.

| Many science fiction writers may wish to be remembered as having been prophetic. As far as Titan goes, Baxter may well rue any such reputation it garners him. |

Against such a setting, the vision and determination of a NASA clique that nonetheless manage to set in progress a mission to Saturn’s eponymous moon seems even more remarkable and, in an echo of Voyage, even more crazy. Indeed, it seems hard to credit Titan’s premise—that the US would embark on a one-way, seven-year mission a billion miles into deep space just to follow up curious results from the Huygens probe—other than by rationalizing it as a desperate, dying reflex of a NASA facing dismemberment at the hands of militaristic philistines. In the end, as the surviving astronauts reach Titan, their efforts to explore and survive become a bitter parody of the success of Apollo and even the fictional Mars mission of Voyage; dedication, ingenuity and what John Wyndham once termed “the outward urge” can only go so far, Baxter seems to say, against an at best indifferent and often hostile universe.

Maybe this was mankind’s last moment, she thought, here on this remote beach, the furthest projection of human exploration. Maybe, in fact, the sole purpose of the human story, fifty thousand years of crying and living and loving and dying and building, had been to deliver her here, now, to this alien beach, the furthest extension of mankind, with her little canister of seeds.

Yet having written one of the bleakest and most depressing novels of his career, Baxter then caps it with an almost Stapledonian coda in which the last two survivors of the mission find themselves revived on a far-future Titan transformed by the Sun’s evolution into a red giant star. Reminiscent of Baxter’s “deep time” novels such as The Time Ships and his “Xeelee” sequence, this section stands apart from the rest of the novel both in tone and in the scope of its vision. Jarring and confusing to some (the Wikipedia entry for Titan notes, but does not attribute, a theory that it represents the dying hallucination of the viewpoint character) this sequence does not so much trivialize the suffering and destruction of the earlier parts of the book as place them in a wider context. Yes, perhaps the universe is indifferent, but the vistas of time and space are such that in the end life and intelligence survives.

Moonseed has a very different feel from Voyage or Titan. It is in some ways a very traditional science fiction disaster novel: an extraterrestrial danger appears, imperils Earth via a series of progressively more severe calamities, and inspires a desperate project to save humanity, or at least some of it.[16] This is a well-worn plot template but one which nonetheless seems to bear regular retelling adorned with the latest science fiction tropes, and Moonseed is no exception, featuring as its cosmic threat an alien nanotechnology that wields quantum physics to turn rock into energy.

Many aspects of Moonseed echo later Baxter novels. In particular, while both Voyage and Titan also feature large casts of characters, only in Moonseed does Baxter explicitly introduce them all at the outset, a technique he was to repeat in Flood. Moonseed also prefigures Flood in its global tour of disasters, its depiction of ineffectual (especially in the UK) official response to disaster, and the prospect of a solution, or at least escape, via a visionary clique’s engineering project. It is in respect of this last point that Moonseed is closest to the other NASA Trilogy novels, with its desperate lunar spaceflight. But while in Voyage and Titan the mission is the novel, in Moonseed it is just part—although an essential and dramatic part—of the main viewpoint character’s personal mission to confront the source of the threat that is tearing the Earth apart.

| My reading of the NASA Trilogy is that this admiration is centered on the resourcefulness and initiative of scientists and engineers under pressure, be it in support of goals that are life-saving (as in Apollo 13), scientific, or even ultimately (as was clearly the case with Apollo) political. |

Indeed, by comparison to Natalie York of Voyage and Paula Benacerraf of Titan, Henry Meacher—the central character of Moonseed—is a most reluctant astronaut; his lunar voyage is a necessary ordeal rather than a goal in itself. And the mission in question is different too, although in an odd kind of way the three novels show a kind of progression of urgency. In Voyage, the Ares mission is a decade and a half in the planning, and in effect becomes the whole US space program; in Titan, the mission to Saturn is put together in three years from the relics of the Apollo and Shuttle programs; in Moonseed, the desperate trip to the Moon is a jury-rigged effort cobbled together in months from a mishmash of Russian capsules and surplus US space probes. A common theme through all three novels is Baxter’s admiration of NASA’s culture of problem-solving; it is not always a culture that solves problems efficiently or well, but when pushed hardest can, as seen on the Apollo 13 near-disaster, work wonders. It is as if, in the NASA Trilogy novels, Baxter pushes this ethos progressively harder, testing his scientists and engineers under ever greater pressure as they assemble titanium and rocket fuel into the machines that will take his characters to their destiny. As Baxter has Meacher ponder:

NASA tended to think of itself as a heroic agency, capable of taking whatever challenges were thrown at it. But the truth was, all the way back to Mercury, they had never launched a manned mission without every aspect of it being timelined, checklisted, simulated and rehearsed […]

Running a mission like this – making it up as they went along – was alien to a NASA culture that went back half a lifetime.

This, to me, illustrates the significance of the space mission element of Moonseed as an element of both the book and the NASA Trilogy as a whole. I have already noted Baxter’s manifest admiration for NASA, even though it is at times tempered by unease at the wisdom and motivation of some of its more grandiose projects. My reading of the NASA Trilogy is that this admiration is centered on the resourcefulness and initiative of scientists and engineers under pressure, be it in support of goals that are life-saving (as in Apollo 13), scientific, or even ultimately (as was clearly the case with Apollo) political. As these examples indicate, NASA has through its very nature been the perfect environment for exploring and depicting this, and in his NASA Trilogy Baxter progressively distills the essence of his admiration. In that regard, the mission in Moonseed—hurried, improvised, desperate, but ultimately successful—can be seen as, for Baxter, the epitome of what NASA’s culture can achieve. In this, he echoes the sentiments of legendary NASA mission controller Gene Kranz, as most widely known in fictionalized form in the film Apollo 13.

Chris Kraft: This could be the worst disaster NASA’s ever faced.

Gene Kranz: With all due respect, sir, I believe this is gonna be our finest hour.[17]

In For All Mankind we now have a well-received TV drama embracing this ethos. Moore has described his vision as being to film the space program he thought he would grow up to see as a child of the 1970s (Inverse.com, 2019). Although For All Mankind has many darker moments, one factor that shines through is how Moore, like Baxter, plainly admires NASA’s spirit of ingenuity and determination. Although production of season two has been delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, it will be fascinating to see how Moore takes this forward.

Endnotes

- ‘Overtly’, as For All Mankind showrunner Ronald D. Moore has stated that the writing team took as the original point of departure that Sergei Korolev, Chief Designer of the Soviet space program, did not die during surgery in 1966 but rather lived and was able to steer the ill-fated N1 heavy launch vehicle project to success. (Interview with Inverse.com, published 15 July 2019.)

- The Encyclopedia Astronautica website is a rich resource for articles on such topics as alternate lunar landing projects and proposals for enhancing the Saturn V rocket, among many others. Beyond Apollo (https://www.wired.com/category/beyondapollo/) presents archived proposals for manned and unmanned missions from the Apollo era.

- D. Shayler, Apollo: The Lost and Forgotten Missions (2002), Praxis, is a 364-page account of Apollo missions ranging from those that were lost through mishap (Apollo 1 and 13) through ones that were cancelled (Apollo 18, 19 and 20) to those that were never more than concepts. Among the latter are the Mars studies that Baxter drew on for Voyage.

- S Baxter, “alt.space”, Vector Jan/Feb 1998, reprinted in Omegatropic (2001) BSFA.

- I must declare my own interest here; with Baxter I co-authored ‘Prospero One’ (Interzone 116), which sits in the same continuity as Voyage and extrapolates the oft-forgotten British space program into the realms of manned spaceflight. We later, slightly less realistically, repeated the exercise in ‘First to the Moon’ (Spectrum SF 6).

- ‘alt.space’, see note 3.

- D. Day, ‘Murdering Apollo: John F. Kennedy and the retreat from the lunar goal’ parts 1 and 2, published online at The Space Review.

- The 1999 BBC radio dramatization discarded this structure in favor of a linear narrative.

- P O’Brian, Master and Commander (1970) Collins, author’s note.

- The original mission plan for Apollo involved ten landings, running from Apollo 11 to Apollo 20, of which the final five would be ‘J-series’ missions with long-duration surface stays, enhanced science and innovations such as the Lunar Rover. Three of those ten were cancelled, leaving six landings (Apollo 13 having aborted) of which only the final three were enhanced ‘J’-missions. Those three accounted for some 75% of the total surface exploration time and rock samples, and 95% of the total distance covered (thanks to the Rovers), suggesting that the cancellation of the others resulted in a disproportionate loss to lunar science. (See D. Shayler, Exploring the Moon: The Apollo Expeditions (1999) Praxis, Ch. 9).

- James Nicholl, rec.arts.sf.written, 19 December 1998.

- Personal communication with the author.

- Interview with Nick Gevers, Interzone 164 (2001).

- R Smith, “The Challenge of Space Power”, (1999) XIII Airpower Journal 1.

- Since this article first appeared in 2011 the United States Space Force has of course become a reality.

- E.g. P Wylie and E Balmer, When Worlds Collide (1933) Frederick Stokes, filmed as When Worlds Collide (1951) Paramount / George Pal, to mention one of many.

- Although the direct quote may have been scripted for the film, Kranz’s sentiments were certainly genuine, as seen from this signed photograph.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.