|

|

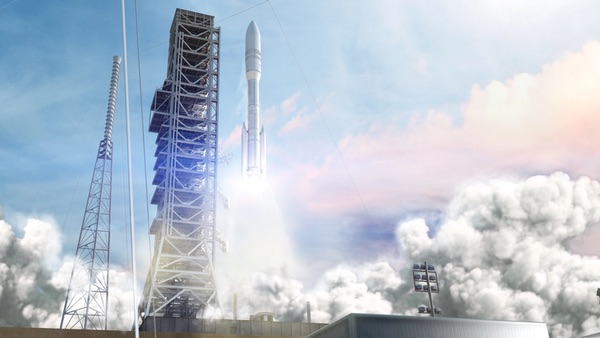

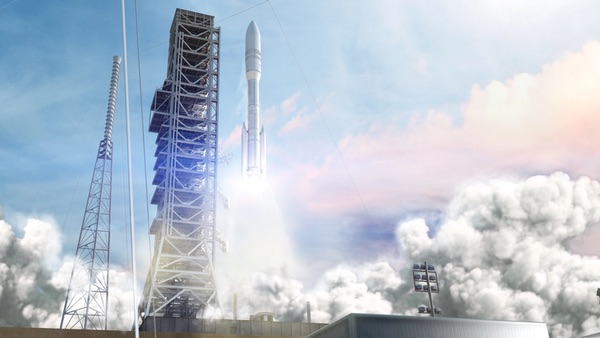

While SpaceX won the Air Force launch competition using its existing Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets, it will have to build a mobile servicing tower (right) at LC-39A to allow for vertical processing of payloads, as well as a stretched payload fairing for the Falcon Heavy. (credit: SpaceX) |

Losers and (sore) winners

by Jeff Foust

Monday, August 24, 2020

In April 2014, Elon Musk declared war on the US Air Force. At a press conference in Washington, he announced that he was filing suit against the service, arguing that it had locked SpaceX out of future military launch contracts with a block buy of launches from rival United Launch Alliance. “Essentially, what we feel is that this is not right,” he said at that event. “National security launches should be put up for competition, and they should not be awarded on a sole-source, uncompeted basis.” (See “SpaceX escalates the EELV debate”, The Space Review, April 28, 2014.)

Six years later, SpaceX would seem to have won that war. That initial suit led to an agreement with the Air Force in early 2015 that ramped up work certifying SpaceX’s Falcon 9 for national security launches, as well as opening up a small number of launches, such as for GPS satellites, to competition. At the same time, there were growing concerns about reliance on Russian engines like the RD-180, which powers ULA’s Atlas V, given worsening US-Russian relations. That prompted an effort to promote development of new launch vehicles with domestic propulsion, while also ensuring competition for military launches.

On August 7, the Department of the Air Force announced the outcome of that effort, formally known as National Security Space Launch (NSSL) Phase 2. SpaceX and ULA would split as many as 34 launches from 2022 through 2027 on a 60/40 basis favoring ULA. That included two initial launches awarded to ULA , valued at $337 million, and one for SpaceX, at $316 million.

“This is a groundbreaking day, culminating years of strategic planning and effort by the Department of the Air Force, NRO, and our launch service industry partners,” Will Roper, assistant secretary of the Air Force for acquisition, said in a statement. “Maintaining a competitive launch market, servicing both government and commercial customers, is how we encourage continued innovation on assured access to space.”

For ULA, which bet the future of the Boeing/Lockheed Martin joint venture on its next-generation Vulcan rocket still in development, winning the NSSL Phase 2 award was a major victory. “ULA is honored to be selected as one of two launch providers in this procurement,” Tory Bruno, president and CEO of ULA, said in a statement. “Vulcan Centaur is the right choice for critical national security space missions and was purpose built to meet all of the requirements of our nation’s space launch needs.”

It would seem to be a major victory for SpaceX as well. After all, six years ago the company went to court to win the right to complete for military launches, and now it’s won a lucrative contract on top of its existing business for NASA and various companies. Moreover, unlike ULA or the other companies than bid on the NSSL Phase 2 program, SpaceX did not have to develop a new vehicle, offering instead its proven Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets.

Yet, there was no congratulatory press release or other statement from SpaceX after it won the NSSL Phase 2 award. Musk refrained from comment on Twitter for nearly a week. When he did weigh in, he was not happy.

“Efficiently reusable rockets are all that matter for making life multiplanetary & ‘space power’. Because their rockets are not reusable, it will become obvious over time that ULA is a complete waste of taxpayer money,” he said in one tweet. A lack of reusability was not acceptable in aircraft, he later said, “So why is this madness acceptable for Boeing/Lockheed rockets?”

SpaceX, of course, has embraced reusability, and demonstrated the ability to reuse booster stages: a Falcon 9 launch last week was the sixth flight of one specific first stage, a new company record. ULA, by contrast, has expressed interest only in a limited form of reusability, recovering just the Vulcan’s BE-4 first-stage engines, and hasn’t set a schedule for doing so. But reusability was not a major factor in the NSSL Phase 2 competition, and the military has been slower to accept use of “flight-proven” Falcon 9 boosters than either NASA or commercial customers.

SpaceX, it appeared, was still upset about what it considered a slight earlier in the overall process. In October 2018, the Air Force issued Launch Service Agreement (LSA) awards to companies to fund development of aspects of their launch systems that would later compete for NSSL Phase 2 awards. ULA received the largest award, valued at $967 million, for supporting work on Vulcan. Northrop Grumman got $792 million for its proposed OmegA rocket, and Blue Origin $500 million for infrastructure for its New Glenn rocket.

SpaceX, though, did not get an agreement, and it filed suit the following May in the Court of Federal Claims, a suit later transferred to a federal district court in California. SpaceX had sought funding to support work on its Starship vehicle, which SpaceX proposed for the most demanding national security missions that could not be fulfilled by the Falcon 9 or Falcon Heavy. The company argued that the Air Force unfairly assessed its proposal and caused “irreparable harm” to the company.

With SpaceX ultimately winning one of the NSSL Phase 2 awards, one might assume that the harm SpaceX experienced was less than irreparable. SpaceX disagrees. In a court filing last week, the company said it was continuing its suit despite winning the contract.

“Unlike its competitors, SpaceX competed in the Phase 2 competition without the benefit of government investment and technical information exchanges under the LSAs,” the company argued, suggesting that ULA’s agreement in particular “may well have contributed to ULA winning 60% of the Phase 2 launches.”

While SpaceX ultimately bid existing vehicles for the NSSL Phase 2 competition, rather than Starship, the company still has development costs. In order to meet the government’s requirement for vertical payload processing—SpaceX processes its vehicles horizontally—the company will have to build a mobile service tower at Launch Complex 39A, enabling the installation of payloads on the rocket once it’s rolled out to the pad and moved to the vertical. SpaceX also plans to develop an extended payload fairing for the Falcon Heavy to accommodate larger satellites.

Some have suggested those costs may be a reason why SpaceX’s single launch announced earlier this month as part of the NSSL Phase 2 awards is worth nearly as much as the two Vulcan launches awarded at the same time to ULA. SpaceX hasn’t disclosed what vehicle will be used for that mission, known only as USSF-67 for the NRO.

While Northrop Grumman has yet to announce its plans for OmegA after losing the Air Force competition, rumors and previous comments by company executives suggest the company will end the program. (credit: Northrop Grumman) |

Diverging fates for the losers

For all of SpaceX’s complaints, it’s worth noting it still won an NSSL Phase 2 contract, with potentially more than a dozen launches depending on the total number of missions awarded over the course of the contract. And even if SpaceX had lost, it would still have plenty of NASA and commercial business to fall back on for the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy.

The two losers in the competition, though, face different situations. Blue Origin hoped to secure an anchor government customer for its New Glenn rocket on top of several existing commercial customers. The company, though, shrugged off the loss.

“We are disappointed in the decision that New Glenn was not selected” for the NSSL Phase 2 competition, said Bob Smith, CEO of Blue Origin, in a statement. “We submitted an incredibly compelling offer for the national security community and the US taxpayer.”

Blue Origin has spent more than $2.5 billion on New Glenn, which has included the rocket itself as well as production facilities and a launch site under construction at Cape Canaveral. With company founder Jeff Bezos’ long-term vision of millions of people living and working in space—not to mention his extreme wealth funding the company—it was unlikely Blue Origin would be deterred by losing a single competition.

“We are proceeding with New Glenn development to fulfill our current commercial contracts, pursue a large and growing commercial market, and enter into new civil space launch contracts,” Smith said in the statement. “We remain confident New Glenn will play a critical role for the national security community in the future.” The company will still have a supporting role in the program, as the supplier of BE-4 engines to ULA.

Northrop Grumman, though, had counted on the NSSL Phase 2 competition to support the OmegA rocket. Earlier this year, the company said that leveraging existing systems, like those developed for the Space Launch System as well as strap-on boosters for ULA’s vehicles, would enable OmegA’s business case to close with only a small number of launches a year. “We’re doing synergies so that we can sustain very, very low flight rates, lower than traditionally you could see in a launch vehicle provider,” Charlie Precourt, vice president of propulsion systems at Northrop Grumman, said at a conference panel in March (see “The launch showdown”, The Space Review, May 11, 2020).

But in an earnings call last month, Kathy Warden, president and CEO of Northrop Grumman, suggested the company would cancel OmegA if it didn’t win an NSSL Phase 2 award. “If we are not successful, we would continue to leverage that investment that we and the Air Force have made through the first two phases of the program into other propulsion activities,” she said. That development effort “was a way to share research and development investment across a product line that we can now utilize for other endeavors.”

As of the end of last week, Northrop had not announced its plans for the future of OmegA, saying it was awaiting a debrief with the Air Force about its proposal (which, in turn, leaves open the possibility of filing a protest.) There have been rumors, though, that company employees have already been told that the company will no longer pursue OmegA.

That’s the hallmark of competition, and taking risks, something Musk talked about at that press conference more than six years ago about his suit against the Air Force. “We’re just protesting and saying that these launches should be competed. If we compete and lose, that’s fine,” he said. SpaceX competed and won, yet doesn’t seem fine with that outcome.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.

|

|