In the paler moonlight: the future’s past in “For All Mankind”by Dwayne A. Day

|

| “For All Mankind” started with an interesting idea: what if the Soviet Union beat the United States to the Moon? From that premise the writers strung out an interesting sequence of events, changing some parts of history while keeping others. |

The first season ended with a time jump ten years in the future, indicating that not only has the United States maintained its lunar south pole base, known as “Jamestown,” but has continued to support its expansion. The season two trailer and some comments by the actors indicate that some of the characters have advanced, and others may have had some setbacks. Margo Madison, the first female flight controller, who blackmailed her way through the glass ceiling, is now a top NASA official (center director? Administrator?). Senior astronaut Ed Baldwin may have been relegated to non-flying status. His longtime friend and flight partner, Gordo Stevens, who suffered a nervous breakdown on the Moon that his colleagues concealed, may have fared worse. Danielle Poole, the first black female astronaut, made a major sacrifice to save Gordo, but may have crippled her career as well: her self-inflicted injury on the Moon would have left everybody at NASA questioning her fortitude and fitness—everybody except Ed and Gordo, who know she did it to justify returning Gordo to Earth and concealing his breakdown.

Although it has advanced the characters, season two’s time jump has meant that many of the plot elements left open in the season finale are not going to be picked up and developed. For example, Baldwin and his wife lost their son in a car accident while Ed was on the Moon, but instead of seeing them deal with their grief, we will see them ten years after this event. During a recent interview, Joel Kinnaman, who plays Baldwin, said that the time jump presented a problem for him. He knew that his character had to work through the loss of his son, as well as his failings as a father that may have contributed to it, but he didn’t know how Baldwin did so, making it difficult to play someone who had suffered a grave wound that never completely healed over.

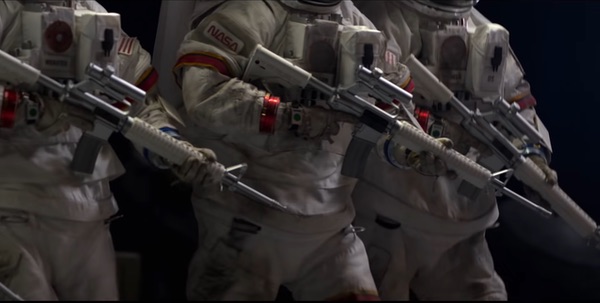

But all this personal drama is set against a geopolitical backdrop that is getting more tense: there are scenes of lunar-suited astronauts arming themselves with rifles, amidst a speech by President Ronald Reagan about the threat to peace posed by the Soviet Union.

With rival American and Soviet bases on the Moon, tensions are high. |

Captured by time

Alternative history has become a niche genre in the entertainment world. “The Man in the High Castle,” based upon a novel by science fiction author Philip K. Dick, depicted an America defeated and occupied by the Axis powers after World War II. Hulu’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” depicts a contemporary America overtaken by a religious government that forbids women from learning how to read, condemning some of them to reproductive slavery and rape. HBO’s award-winning “Watchmen,” which recently cleaned up at the Emmy’s, was set in an altered American landscape regarding the police and their relationship to the citizenry. “The X-Men” movie franchise evolved to a storyline with super beings changing American history during Richard Nixon’s presidency. All of these examples are entertainment, but some have pushed their premises to question American history and culture.

| “For All Mankind” has a different set of challenges in terms of storytelling—it is both about our past, and our future, while also inevitably being a commentary about the present. |

There have been a number of TV shows that have sought to depict a near-future America, although not always in the pursuit of explicit social messages. In the 2010 book Space and Time: Essays on Visions of History in Science Fiction (edited by David C. Wright Jr. and Allan W. Austin), historian Korcaighe P. Hale wrote about near-future science fiction and how it was framed, if not captured, by its writers’ concepts of the present as well as the past. She noted how several science fiction TV shows of the past few decades have been based upon their writers’ views of the major issues of the day, even when set decades in their future. From our current perspective, some of these shows now appear dated and irrelevant as subjects that were topical when they aired have long ceased to be relevant. Hale’s essay title highlights the dilemma: “Too Close for Comfort? Exploring the Construction of Near Future Historical Narratives in Science Fiction Television.”

Setting a program in the near future restricts the writers and what they can do. In contrast, as Hale noted, setting a science fiction show in the far future (or, alternatively, “a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away”) can free up the writers from having to reference—and be limited by—historical or current events that the audience is familiar with. Setting a story in a far distant future can be liberating in terms of storytelling. But it also restricts the writers’ ability to use the show to make social commentary, and their ability to use familiar historical and cultural reference points in their storytelling.

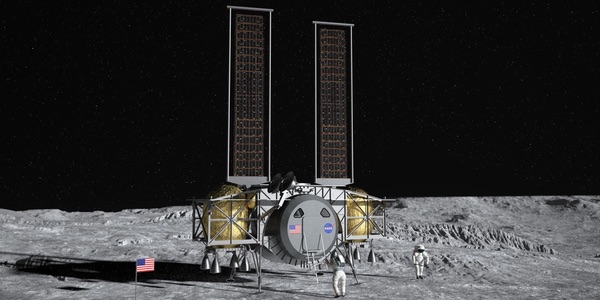

“For All Mankind” has a different set of challenges in terms of storytelling—it is both about our past, and our future, while also inevitably being a commentary about the present. The show’s setting in the 1960s and, for season two, the 1980s, represents a time decades in our past, but still within the living memory of many people. Yet the stories depict a space program that never happened, but still might happen in some way. The Jamestown lunar base in the show is not that different from concepts NASA and its contractors are currently studying. Perhaps in the coming decades, NASA could build something that looks a lot like Jamestown.

“For All Mankind” seeks to depict realistic technology and events. One image is from the show, another is a currently proposed lunar lander.  |

But the show’s writers live in the United States of the present, and this certainly informs what they write about. The first season included a major subplot about Mexican migrants coming across the border that was inevitably inspired by the false hysteria about migrant caravans leading up to the 2018 elections. This second season will inevitably be informed by today’s politics and cultural upheaval, although because eight episodes were finished by the spring, they will reflect the writers’ perspectives in 2019.

Then again, maybe the counterfactual history of the show is not that different than the situation faced by writers of other near future shows. Historian Korcaighe Hale explicitly noted the similarity between counterfactual history and science fiction: “science fiction exists within this same milieu: hovering at the edge of what may be. The counterfactuals in history are innumerable, and like a theoretical multiverse, every historical moment is possible. Perhaps that is where near future shows fall short: by limiting the possibilities of the future, they reduce the attraction of their vision.”

“For All Mankind” has sought to demonstrate the limits of historical daydreaming. For example, the show posited that NASA would recruit and fly women astronauts a decade before this happened in real life. But NASA’s leap forward for women’s rights did not change many fundamental aspects of American society. Similarly, the first gay woman to fly in space stayed in the closet and engaged in a sham marriage to keep her job—homosexuality was still a firing offense at the time. One of the show’s themes is that social change is not simple or easy, and while a single event could be different in the alternative timeline and could have longer-term ramifications, the attitudes of millions of people rarely change over short time spans. We can put a woman on the Moon, but sexism will not disappear.

| One possibility for the show is that while the geopolitical situation on Earth deteriorates, there is some kind of détente achieved on the Moon. Maybe it is human spaceflight and the joint exploration of the Moon that leads to a more peaceful future. |

As for the show’s political landscape, there are interesting places it could go. “For All Mankind” bears more than a passing resemblance to a French counterfactual graphic novel series called “Jour J” that produced an issue in 2010 focusing on the Apollo program. The issue, published in English in 2019 and titled “Russians on the Moon!”, depicts a world where Neil and Buzz are killed by a micrometeorite during their descent to the lunar surface. Valentina Tereshkova then becomes the first person to walk on the Moon. In response to this setback, Richard Nixon calls for the establishment of an American moonbase. A decade later, the American base “Eagle” faces the Soviet base “Galactika,” but something odd and secretive is happening between them. An astronaut arriving at the Eagle base sets out to investigate what is going on only to discover that despite the Cold War, the Americans and Soviets have established covert cooperation on the Moon, helping each other out without the knowledge of their own governments. Perhaps “For All Mankind” will mimic this storyline.

Where exactly “For All Mankind” is taking its story is unclear. Show creator Ronald D. Moore, who worked on “Star Trek” starting in the 1980s, has said that he was interested in exploring the idea of how our space program could eventually connect to the world depicted in the various “Star Trek” series. One possibility for the show is that while the geopolitical situation on Earth deteriorates, there is some kind of détente achieved on the Moon. Maybe it is human spaceflight and the joint exploration of the Moon that leads to a more peaceful future. We’ll have to wait for season two—date still unknown—to find out how whether our future really was wonderful after all.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.