The little satellite that could (part 2): from Triana to DSCOVR to orbitby Dwayne A. Day

|

| By 2003, DSCOVR was stored in a white metal crate underneath a stairwell inside a clean room in building 29 at Goddard. There it would stay, year after year. |

Although Triana was ostensibly able to fly on a future shuttle launch, the satellite was not placed on any launch manifests throughout 2001. By 2002, the NASA administrator announced that shuttle flights would be reduced from six to four per year, further limiting the opportunities for launching the spacecraft. NASA Earth science officials began considering foreign offers to launch Triana. In early 2002 there were reports that Triana could possibly fly on a European Ariane rocket. In May 2002 it was reported that Triana could be launched commercially on a Russian Cyclone rocket, without the participation of the Russian government, although Ariane 5 and Russia’s Dnepr rockets were also options.[2]

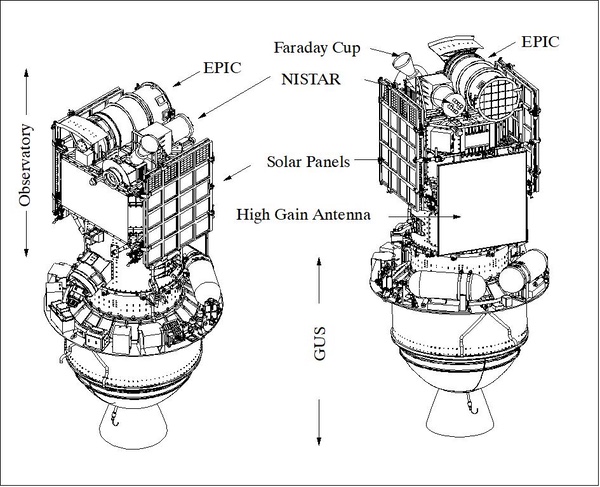

Illustration showing the DSCOVR in configuration for a space shuttle launch. The satellite would have been launched sideways to the direction of flight. Later, when it was considered for a Falcon 9 launch, the satellite had to be tested for vertical loads. (credit: NASA) |

Triana’s principal investigator, Scripps researcher Francisco Valero, wrote a letter to Aviation Week & Space Technology explaining that “Synergism, made possible by the deep-space location of Triana, will multiply the scientific return of our investment in space. Triana is the first of a new generation of deep-space platforms that will help advance the Earth sciences to a new level.”[3] Despite Valero’s advocacy, Triana’s problems were not in the stars but in politics. Throughout 2002, NASA remained silent on the spacecraft some had nicknamed “Goresat.”

By early January 2003, before the launch of the STS-107 mission that was originally supposed to carry Triana into space, NASA was reportedly considering the possibility of launching Triana on a space shuttle Columbia research flight in 2004 or early 2005, after construction of the ISS wound down. This followed a decision by the NASA administrator to increase the shuttle flight rate to five per year, creating an opportunity for a non-ISS research flight that could carry Triana. Trade publication Space News published an editorial with the title “Triana Should Fly,” stating that “There is no reason why NASA should not be able to identify a dedicated space shuttle research mission in 2004 or 2005 that could launch” Triana on its planned mission.[4]

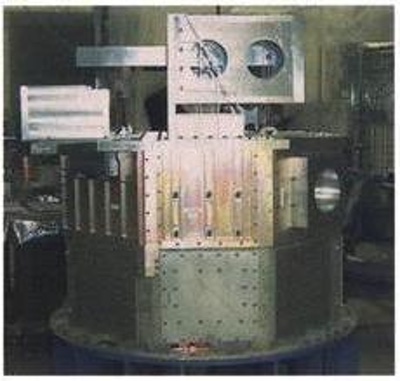

The main structural component of the Triana satellite. This image was probably taken in 2000 before any instruments were complete or added to the spacecraft. Triana was controversial from the start due to its ties to Vice President Al Gore. (credit: NASA) |

Grounded indefinitely

On February 1, 2003, the Columbia broke up during reentry, killing its seven-person crew and substantially altering NASA’s plans for the future. Triana’s hopes of a shuttle launch evaporated.

That same year, in an effort to distance the spacecraft from its ties to Al Gore and to better emphasize its Earth science mission, NASA renamed Triana the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR). But Dick Armey, a Republican congressman from Texas not exactly known for his bipartisan views, derided the satellite. “This idea supposedly came from a dream,” he said. “Well, I once dreamed I caught a 10-foot bass. But I didn’t call up the Fish and Wildlife Service and ask them to spend $30 million to make sure it happened.” Many of the articles about the mothballing of the satellite had specifically mentioned Gore’s name in their titles and it was a tough legacy to shake.[5]

Triana mission patch. The spacecraft was renamed DSCOVR in 2003. (credit: Roger Guillemette) |

By 2003, DSCOVR was stored in a white metal crate underneath a stairwell inside a clean room in building 29 at Goddard. A tube pumped in a steady supply of dry nitrogen to minimize contamination. By that time, the satellite had 1,500 to 2,000 hours testing on most components. But there it would stay, year after year.[6]

In 2004, Ukraine offered a free launch for DSCOVR on a Ukrainian rocket. NASA declined the offer, apparently because of restrictions on the launching of sensitive American space technology on foreign rockets.[7]

Following the Columbia loss, senior NASA managers informed scientists that the program was still a priority. But by early 2006 the mission was reportedly “terminated.” Soon after, a Miniature Inertial Measurement Unit (MIMU) that was originally built for Triana was selected to be refurbished and installed aboard the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), the first component in the Bush administration’s plan to return humans to the Moon. LRO required three, and NASA officials decided to procure two new MIMUs from their manufacturer, Honeywell, and refurbish the Triana one. Whereas Triana had originally used leftover parts, now it was being cannibalized for other programs—ones that originated in the Bush administration.[8] Eventually, the LRO team replaced the MIMU they borrowed from DSCOVR.

Although the spacecraft was still in limbo, NASA did not take any actions to scrap it. By 2006, scientists with the National Weather Service’s Space Environment Center were growing concerned that the Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) satellite, launched in 1997, was three years past its design life. ACE provided about an hour’s advance warning of solar events that could create geomagnetic storms that could knock out power grids. DSCOVR had solar wind instruments that could supplement ACE. According to principal investigator Francisco Valero, DSCOVR could produce weather data to the Space Environment Center within five minutes of collection.[9]

In 2007, NASA estimated that refurbishing DSCOVR, launching it on a Delta 2 rocket, and operating it would cost $205 million, although there was no indication that this was planned.[10]

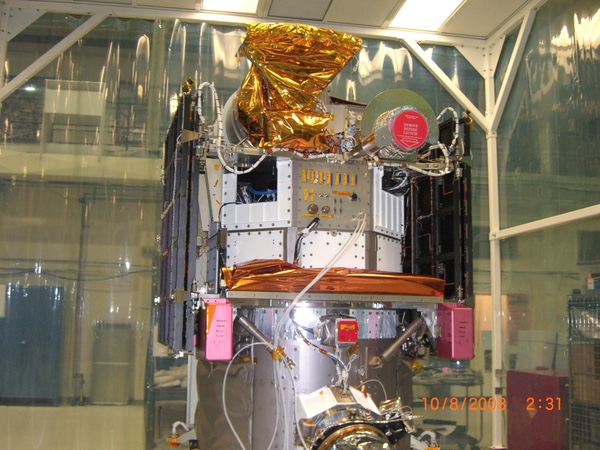

Finally, after eight years in limbo, in October 2008 George Bush signed a NASA reauthorization bill that ordered NASA to develop a plan for DSCOVR. NASA officials soon entered discussion with NOAA and the Air Force about the spacecraft, but there were early reports that the Earth-facing EPIC and NISTAR (National Institute of Standards and Technology Advanced Radiometer) instruments might be stripped from the spacecraft, reportedly to save money, an idea that one scientist referred to as “appalling.”[11]

| The reactivation of DSCOVR also came with an important change in ownership: although NASA owned the spacecraft and was refurbishing it, NOAA and the US Air Force were now responsible for the mission, which was to serve as an early warning system for solar events. |

When Al Gore had first conceived of Triana, he was only interested in an Earth-facing camera to photograph the planet. As NASA worked on the design, the agency conceived instruments that would also provide Earth science data, but then added Sun-facing sensors that could provide advance warning of major solar events that posed a threat to satellites and ground-based power grids. There was a clearer need for those Sun-facing sensors than the more ambiguous Earth-facing ones, which made the Earth sensors a greater target for Republicans—if they could strip the satellite of those sensors, or turn them off, they could strike an ideological blow against Gore. Throughout the Bush Administration, there was no interest by Republicans in the White House or Congress in launching a satellite that was so closely tied to a Democratic vice president.

Despite the politics that kept the spacecraft grounded, NASA civil servants had no desire to offend Democrats in Congress, or in a future White House, by scrapping the spacecraft, and it was easy to simply keep it in storage—usually. Robert Smith, the Triana instrument systems manager and the DSCOVR deputy project manager, remembers having to work with another project to keep the satellite under the stairs at the Goddard clean room, because that location was needed for another mission.[12] But with Bush’s term coming to an end, there was a possibility that a new administration could revive the dormant project. Surprisingly, any progress at putting DSCOVR into orbit proved far slower than expected.

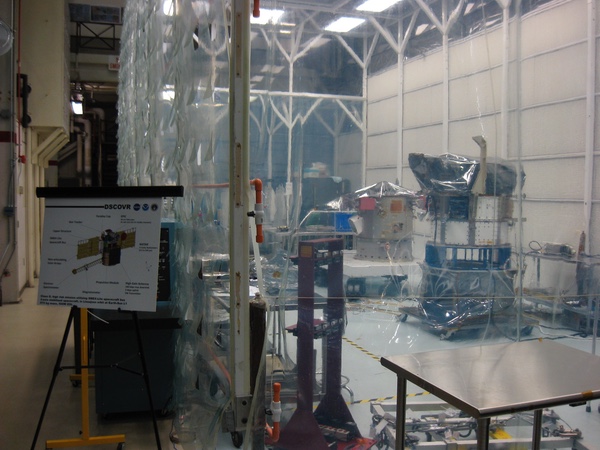

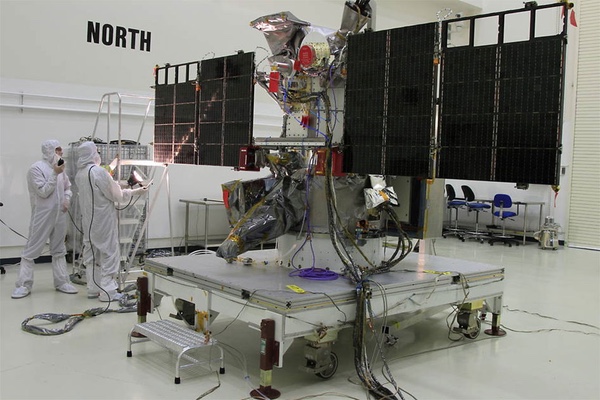

The DSCOVR spacecraft was removed from storage in October 2008, but did not launch until February 2015. Here it is in a cleanroom tent at Goddard Space Flight Center in 2012. (credit: Dwayne Day) |

Like a Phoenix from the ashes

In January 2009, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center produced a report funded by NOAA known as the “Serotine Report,” named after a pine tree that opens its seeds after a forest fire—Triana had survived a firestorm and was now reborn as DSCOVR with this renewed interest from NOAA.[13] The report estimated the cost of finishing the satellite and operating it would be $47.3 million. This included a spacecraft aliveness test and an 18-month schedule. NOAA was appropriated $31.1 million to start this process.

As a result of the report, technicians began inspecting DSCOVR. They tested the pressure in the propulsion tank and found it sound. They also began a careful review of the material properties of all spacecraft components to determine how they aged during eight years in storage. In addition, they conducted tests on spare parts to see how they performed compared to when they were originally manufactured. Both EPIC and NISTAR underwent a $2 million refurbishment. NASA completed three months of tests on DSCOVR ending in February 2009.

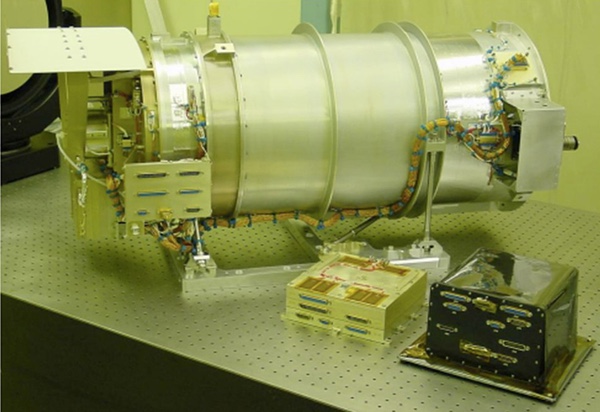

The EPIC Earth-facing instrument. This instrument was one of the most controversial on DSCOVR. There were proposals to remove it before launch, and even to turn it off after the spacecraft had become operational. The instrument has taken some unusual and striking images of the Earth and Moon. (credit: NASA) |

Smith noted that while the spacecraft had been in storage, the science behind the EPIC measurements had changed, requiring a change the EPIC instrument. They changed the bandpass of some of the filters, meaning the color of light that was let through the filters. EPIC also had some known problems with stray light scattering inside the instrument, and they fixed this by tilting the detector and added an antireflective coating to the filters. The work was performed by Lockheed Martin, and they had to conduct comprehensive alignment and recalibration to confirm that the problem had been reduced to an acceptable level. According to Smith, “later software modifications helped to further reduce the stray light effects and improve the science data.” NISTAR also underwent motor performance testing.[14]

In 2009, the federal budget contained $9 million specifically allocated “to refurbish and ensure flight and operational readiness of DSCOVR Earth science instruments” EPIC and NISTAR. EPIC was built by Lockheed Martin in Palo Alto, California, and NISTAR was built by Ball Aerospace in Boulder, Colorado. Scripps managed the contract and had the Triana science operations center, which was replaced by a science operations center at Goddard.

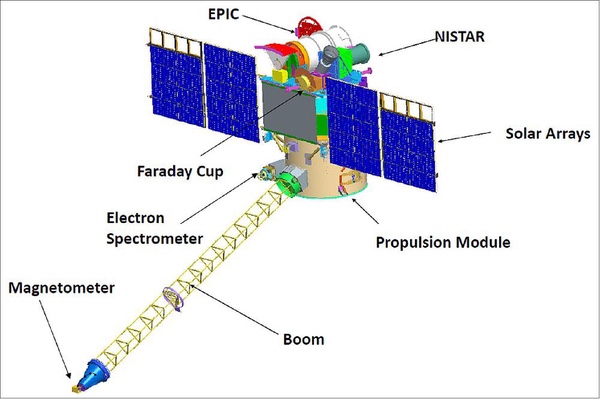

The Plasma-Magnetometer Solar Weather Package, or PlasMag, was built at Goddard. The Faraday Cup was part of PlasMag and was built by MIT. DSCOVR had from the start also included a small instrument known as the Pulse Height Analyzer developed by Dr. Epaminondas Stassinopolis at Goddard to measure electron displacements in a programmable device. This provided some data on how space weather affected electronics.[15]

Francisco Valero indicated that science team members had been working on the mission on a voluntary basis for years. Now that they had funding, they could review the mission’s science objective and update software. Valero believed that the satellite could be ready for launch by 2010. He also noted that DSCOVR could possibly launch aboard a new rocket, SpaceX’s Falcon 9, which was not at the time an approved launch vehicle under contract to carry NASA payloads.[16]

The reactivation of DSCOVR also came with an important change in ownership: although NASA owned the spacecraft and was refurbishing it, NOAA and the US Air Force were now responsible for the mission, which was to serve as an early warning system for solar events. DSCOVR’s PlasMag instrument monitored plasma, particles and magnetic fields streaming out of the Sun. Solar events can affect satellite electronics as well as terrestrial power supplies. The Air Force was interested in the operational space weather data, but also interested in proving that an optical payload could be launched on a Falcon 9, therefore making the rocket available for other Air Force payloads.[17]

| The launch would not only place DSCOVR in orbit, but also test the Falcon 9 rocket, possibly including some additional requirements for the rocket to demonstrate, such as an upper stage coast phase. |

But for that year and into the next there was no active effort to prepare the spacecraft for launch. In February 2011, the Obama Administration’s proposed NOAA budget included a $47 million request to convert the satellite into a NOAA space weather monitoring satellite.[18] DSCOVR was now formally tapped to replace the aging ACE satellite. Despite the new money and Valero’s optimism, DSCOVR remained grounded. Later that year, NOAA considered adding an instrument called the Total Irradiance Monitor to measure the Sun’s total energy output. Such an instrument had been carried on NASA’s Glory satellite, which was destroyed in a March 2011 launch failure.[19]

In July 2011, the House Appropriations Committee recommended against funding the project in 2012. But later in the year, Congress appropriated $30 million of the $47 million request. That would enable NOAA to move ahead with the mission, which could be launched in 2014.[20] Later that year, Senate appropriators urged the Department of Defense to pay for DSCOVR’s launch using a SpaceX launch vehicle. The appropriators believed that funding a SpaceX launch would “assist new entrants in meeting the requirements for mission assurance.” The launch would not only place DSCOVR in orbit, but also test the rocket, possibly including some additional requirements for the rocket to demonstrate, such as an upper stage coast phase.[21]

In January 2012, DSCOVR became a flight project again and Al Vernacchio became the program manager.[22] In February 2012, the program team presented several options to an evaluation team regarding EPIC and NIST, the “legacy instruments” from the original mission. These options included operating the instruments as designed, replacing them with mass models, and flying them in “non-functional mode,” meaning shut off. Mission planners decided to fly the instruments as originally planned.

DSCOVR’s science objectives by that time were to “continue solar wind measurements in support of space weather requirements providing 3-dimensional distribution function of the proton and alpha components of the solar wind.” This would be measured by the satellite’s Faraday Cup. The other primary science objective was to measure the “3-dimensional magnetic field vector” using the fluxgate magnetometer. A third PlasMag instrument, the Electron Spectrometer, did not provide operational data that NOAA could use, so NASA funded inclusion of that instrument.[23] A secondary objective was “to observe the Earth from the unique Earth-Sun L1 perspective.” A tertiary objective was to measure the energetic particle environment. The mission had so far cost $249 million (in fiscal year 2007 dollars), the cost from project initiation all the way up to the placement of the satellite in “stable suspension” at Goddard.

In December 2012, the US Air Force announced that Space Exploration Technologies (SpaceX) won two competitions to launch satellites. SpaceX’s Falcon 9 v1.1 was approved to launch satellites as part of the Orbital/Suborbital Program-3 contract. OSP-3 was to include 10–12 launches through 2017 at a cost of $900 million. The DSCOVR launch was expected to cost about $100 million.[24]

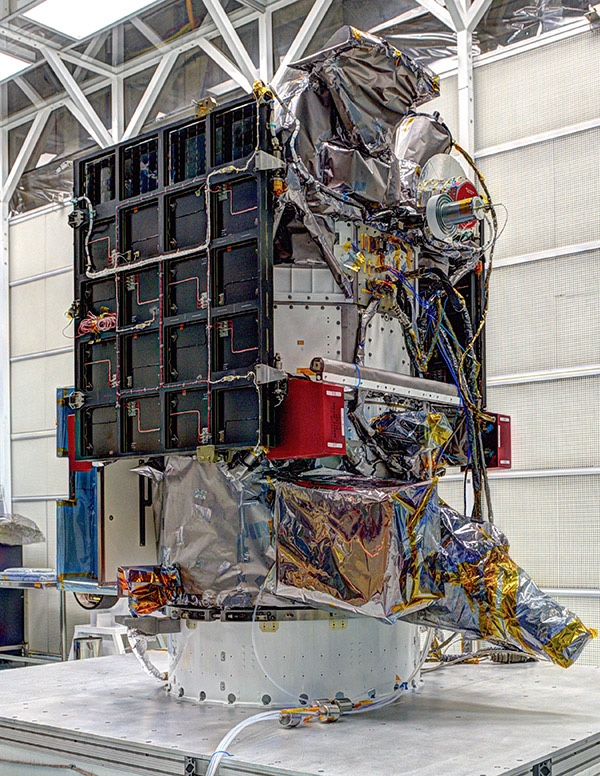

The satellite in final configuration at Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, before shipping to Florida for launch. (credit: NASA) |

Reaching orbit

By September 2014, DSCOVR was scheduled for a January 2015 launch. In June, Senate appropriators had approved a 2015 spending bill that would have required that NOAA transfer DSCOVR back to NASA—something that neither agency was interested in doing. Ultimately, the transfer did not take place.[25]

In September 2014 a major solar event served as a reminder of the need to carefully monitor the Sun and provide warning of so-called coronal mass ejections. Such CMEs could disrupt GPS signals and overload electric grids. Fortunately, the storm did not cause any major effects but did produce some impressive auroras.

According to Thomas Berger, a solar physicist who had taken the job of Director of the Space Weather Prediction Center, DSCOVR was an important adjunct to space weather monitoring capability because it would be the first “operational” solar wind monitor, as opposed to the ACE, which was a research spacecraft. An operational sensor had to be available 365 days a year. According to NOAA, “DSCOVR will typically be able to provide 15 to 60-minute warning time before the surge of particles and magnetic field” resulting from a coronal mass ejection, associated with a geomagnetic storm reaches Earth.[26]

The DSCOVR satellite in Florida before final integration atop its rocket. (credit: NASA) |

By this time, providing imagery of the Earth was a secondary DSCOVR mission. The original plan for Triana was to provide real-time images of the Earth. Instead, DSCOVR would take four to six images per day and transmit them with a one-day delay. Robert Smith indicates that they eventually ended up taking three images (red, green, blue) every fifteen minutes, and the full set of ten filter images every hour.[27] The cost of the mission, including the cost of hardware originally built for Triana, was now estimated at $340 million. According to Stephen Volz, assistant administrator of the NOAA Satellite and Information Service, the cost was split among NASA, NOAA, and the Air Force. NOAA was anticipating spending $104.8 million over its lifetime.

On November 20, DSCOVR arrived in Florida for integration with the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. The launch cost the Air Force $97 million. The launch was originally scheduled for January 23, but by late December, a delayed supply mission to the ISS had forced a delay in DSCOVR’s launch to no earlier than January 29.[28] The launch then slipped into February.

The satellite and its Falcon 9 payload shroud. The Air Force paid for the launch in part to demonstrate that the Falcon 9 could launch future national security payloads. (credit: NASA) |

Finally, DSCOVR lifted off on February 11, 2015, on its third attempt after previously scrubbing because of a power surge and then high winds. SpaceX had planned to attempt to retrieve the Falcon 9’s first stage but was unable to do so because the recovery barge was kept in port due to bad weather. DSCOVR’s trip out to its operational orbit at the Lagrange 1 point then took several months, and DSCOVR finally reached its intended orbit more than 1.5 million kilometers from Earth around 8 pm Eastern Daylight Time on June 7, only a decade and a half late.

After reaching its assigned orbit, Triana’s EPIC instrument produced images of Earth, including a “stunning” gif of the Moon crossing in front of the Earth.[29]

| Although it was finally operating as planned, DSCOVR was soon embroiled in new political troubles. |

DSCOVR’s checkout was scheduled to be completed by NASA by October 27, at which time it would turn over the spacecraft to NOAA. DSCOVR would then take over space weather duties from the ACE satellite, which had been designed for a five-year lifetime but had been operating for 18 years.[30] Once it reached its operational orbit, DSCOVR went through an extended commissioning phase. The spacecraft’s magnetometer worked well, but the Faraday Cup, which measured wind speed, density and temperature, experienced problems. It only provided data every 20 seconds instead of every second, as planned. The problems delayed DSCOVR’s commissioning to July 2016.[31]

NOAA was then studying a Space Weather Follow-On, which would consist of multiple satellites and provide one to four days of advance warning of space weather events. The first spacecraft would feature several instruments, including a new one, a compact coronagraph, and would operate in Lagrange point 1, like DSCOVR. NASA and the Naval Research Laboratory would collaborate, with the NRL providing the coronagraph. The new program included a second satellite for launch in 2027. It would replace both DSCOVR and the ESA-NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft. SOHO had a coronagraph instrument to collect data on coronal mass ejections on the Sun.[32]

Launch of the DSCOVR satellite on February 11, 2015. The original plan had been to launch the satellite in 2001, but politics kept it grounded. After launch, it took months for the spacecraft to reach its operational orbit, and more months to finish its checkout. Two years after launch, a Republican White House tried to shut off DSCOVR's two Earth-facing instruments, which owed their existence to a Democratic vice president nearly nineteen years earlier. The instruments were left on, and DSCOVR continues operating today as a solar storm early warning system. (credit: NOAA) |

Politics never sleeps

Although it was finally operating as planned, DSCOVR was soon embroiled in new political troubles. In March 2017 the White House’s fiscal year 2018 budget proposal deleted funding for several Earth science programs focused on climate, as well as DSCOVR’s “Earth-viewing instruments”—EPIC and NISTAR. The White House also asked Congress to delete $90 million from NOAA weather satellite programs and $50 million from NASA science programs in any fiscal year 2017 spending bills then under consideration.[33] There was no explanation of how much money would be saved by turning off two instruments on a spacecraft that had several others, and it was not hard to suspect that a Republican administration was trying once again to bury something that was associated with a Democratic vice president who had left office 16 years earlier.

The proposed cuts resulted in complaints raised by the Earth science community, but NASA officials downplayed the impact on the Earth science program. In the meantime, DSCOVR continued operating, although researchers pointed out that even with the spacecraft’s Sun-facing instruments, the nation’s space weather prediction capabilities were still rather limited.[34]

The proposed NASA budget cuts came under fire not only in the scientific community but also in Congress, first in the House and then in the Senate, although a draft bill in the House cut Earth science even more than the president’s proposed budget. In June 2017, the NASA budget was discussed during a hearing by the Senate Appropriations Committee’s Commerce, Justice and Science subcommittee, where NASA acting administrator Robert Lightfoot explained the DSCOVR cuts: “We believe we have 20 spacecraft already on orbit that give us the same data, if not better data, based on the sensors that we have, and we’d rather put our research and analysis efforts around those spacecraft rather than DSCOVR.” By July, the Senate had restored funding for the deleted Earth science programs, including DSCOVR, although the budget had still not been passed by February 2018.[35]

In February 2018, the administration again proposed cutting the same Earth science programs—including DSCOVR’s Earth facing instruments—that it had proposed cutting a year earlier. But by June, as it had the previous year, the Senate restored the funding for the fiscal year 2019 budget.[36]

After two years of having them rejected in the Republican-controlled Senate, the administration did not repeat its proposed cuts to the Earth science budget in fiscal year 2020 and instead proposed $1.7 million for DSCOVR operations, identical to the amount the program received the previous year.[37]

The DSCOVR logo emphasized the spacecraft's role as a solar observation and solar storm warning platform. It de-emphasized Earth observation. Compare this logo to the earlier Triana patch, which featured the Earth much more prominently. (credit: NOAA) |

A new threat

Having weathered yet another political threat, DSCOVR now faced a new one from its own systems. In June 2019 DSCOVR experienced a problem with its positioning system, and on June 27 it went into “safehold.” Previous safeholds had lasted only a few hours and were probably caused by cosmic rays, but this one was much more serious.[38]

| Had Triana emerged as the dream of an Earth scientist, it probably would not have been ridiculed in the way it was, but it probably also would never have been funded.s |

By September, NOAA announced that a private company was analyzing the problem with DSCOVR and NASA was working on a “software fix” to restore DSCOVR to operations. But NOAA also indicated that they did not expect it to come back online until the first quarter of 2020. NOAA did not provide many details on what had caused the problems, although it referred to “an earlier performance issue.” In the meantime, NOAA was relying on ACE—launched in 1997 with a five-year design lifetime and now 22 years old. NOAA was also relying upon SOHO, which had been launched in 1995 and was far past its design life as well.[39]

A NOAA official stated that the Space Weather Follow-On would eventually replace all these satellites. But until that happened, two very old satellites and a newer, malfunctioning one, were all the United States had.[40] In an example of space planning irony, at several points during the development of Triana/DSCOVR the “aging” SOHO and ACE missions were used as justifications for the need to launch DSCOVR. Yet both spacecraft remain operational even today, and some estimates are that ACE could continue until 2024.

Robert Smith noted that DSCOVR project scientist Adam Szabo has identified an interesting and puzzling observation by the spacecraft’s Sun-monitoring instruments. ACE produces data every minute, but DSCOVR takes measurements far faster, every second. The DSCOVR data shows a small, increasing oscillation in front of the large surge defining a solar storm, a phenomenon that had never been seen before, proving that there is much we still do not know about our Sun.

On March 2, 2020, NOAA announced that DSCOVR was back in operation, more than eight months after it had gone into safehold.[41] Despite a hard-luck life, DSCOVR was not dead yet.

DSCOVR has Sun-facing instruments and Earth-facing instruments. The high-gain communications antenna is mounted on the same side as the Sun-facing instruments. The instruments that face the Sun are important for warning of solar events that can have bad effects on Earth and space-based electronics. (credit: NASA) |

The stuff dreams are made of

Many spacecraft begin as dreams. The Voyagers, which revealed more of the solar system than any other machines created by humans, started out as a dream to expand human knowledge. Viking was to large extent fueled by longstanding human imaginings about life on Mars. Spacecraft begin as ideas, they all emerge from the human mind, although they may be ideas intended to serve pragmatic and practical goals like tracking hurricanes, or more philosophical ones, like searching for the water and carbon and life on Mars. Had Triana emerged as the dream of an Earth scientist, it probably would not have been ridiculed in the way it was, but it probably also would never have been funded.

In 2001, Triana’s principal investigator Francisco Valero sought to better explain the vision behind the spacecraft, writing that it would “allow the study of Earth and its climate as a single system from the vantage of deep space.” Such a “unified, integrated Earth observation system,” Valero wrote, was “a long-standing dream of Earth scientists.” But such lofty ideas, even if valid, are often ground down by Washington’s partisan environment. Triana became much more practical. It became DSCOVR. It also became in some ways much more ordinary.

Al Gore’s idea was for Triana to be a mirror in space, allowing people on the ground to gaze at their own planet the same way that they can gaze at the Moon or Mars. It may have been a foolish dream, but it was still a noble one.

Endnotes

- “NASA Mothballs ‘Goresat,’” Aviation Week & Space Technology, April 2, 2001, p. 23.

- Jeff Ristine, “Launch Looks Distant for Scripps Spacecraft,” San Diego Union Tribune, January 13, 2002; “NASA exploring options with other countries to launch Triana,” Aviation Week Aerospace Daily, Vol. 202, No. 31, May 13, 2002; Brian Berger, “NASA Considers Use of Non-U.S. Rockets for Triana Launch,” Space News, February 11, 2002, p. 10; Martin B. Houghton, “Getting to L1 the Hard Way: Triana’s Launch Options,” Libration Point Orbits and Applications, June 10-14, 2002; James R. Asker, “Triana Revisited,” Aviation Week & Space Technology, May 13, 2002, p. 23.

- Francisco P. Valero, “Triana Provides Flexibility,” Aviation Week & Space Technology, June 10, 2002, p. 6.

- “Triana Should Fly,” Space News, January 13, 2003, p. 14; Brian Berger, “Controversial Triana Satellite May Fly in 2004,” Space News, January 6, 2003, p. 3.

- Bill Donahue, “Who Killed the Deep Space Climate Observatory?” Popular Science, April 6, 2011; “Who Killed the Deep Space Climate Observatory?”; Melissa Harris, “Satellite destined for storage space politics, delays keep project grounded,” South Florida Sun-Sentinel, July 29, 2001, p. 1G; “Al Gore’s Earth-Observing Satellite Caught in Budget Pinch,” Dow Jones Newswires, August 9, 2001; Joel Achenbach, “For Gore Spacecraft, All Systems Aren’t Go,” The Washington Post, August 8, 2001, p. 1.

- Quang-Viet Nguyen/JASD Program Executive, “Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) Mission Briefing,” Heliophysics Subcommittee Meeting, February 27, 2012.

- “Who Killed the Deep Space Climate Observatory?”

- Andrew Lawler, “NASA Terminates Gore’s Eye on Earth,” Science, January 6, 2006, p. 26; “NASA Recycles Triana Component for Lunar Orbiter,” Aviation Week’s Aerospace Daily & Defense Report, Vol. 217, No. 13, January 23, 2006; Frank Morring, Jr., “Lunar Recycling,” Aviation Week & Space Technology, January 23, 2006, p. 15.

- Brian Berger, “Lack of Backup for Solar Wind Worries Forecasters,” Space News, April 17, 2006.

- Becky Iannotta, “NASA to Revive DSCOVR Mission with Funding From Congress,” Space News, April 6, 2009, p. 15; Turner Brinton, “House Panel Denies Funding for Pair of NOAA Satellite Projects,” Space News, July 12, 2011.

- Ashley Yeager, “Satellite risks losing sight of Earth,” Nature, 456, 292 (2008), November 19, 2008.

- Comments by Robert Smith to Dwayne Day, August 23, 2021.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.; Becky Iannotta, “NASA to Revive DSCOVR Mission With Funding From Congress,” Space News, April 7, 2009.

- Comments by Robert Smith to Dwayne Day, August 23, 2021.

- “NASA to Revive DSCOVR Mission with Funding From Congress”; Stephen Clark, “NOAA taps DSCOVR Satellite for Space Weather Mission,” Spaceflight Now, February 21, 2011.

- Turner Brinton, “NOAA to Assess Options for Scaling Back JPSS Program,” Space News, May 2, 2011; Turner Brinton, “House Panel Denies Funding for Pair of NOAA Satellite Projects,” Space News, July 12, 2011.

- “NOAA Administrator Warns of Greater Disruption from Solar Maxima in 2012,” Space News, December 19, 2011.

- “Senate Urges Pentagon to Loft Grounded Satellite,” Space News, September 26, 2011; “Editorial: Dscovr Competition,” Space News, November 8, 2011; “Triana Satellite Pulled From Storage for Competitive Test Launch,” Aviation Week Aerospace Daily & Defense Report, Vol. 238, Issue 26, May 6, 2011.

- Comments by Robert Smith to Dwayne Day, August 23, 2021.

- Ibid.

- Amy Butler, “SpaceX Wins Its First USAF Contracts,” Aviation Week & Space Technology, December 10, 2012; Sandra Erwin, “F-35 program official named No. 2 at Space and Missile Systems Center,” Space News, February 13, 2020.

- Dan Leone, “Stopgap Funding Bill Keeps DSCOVR, Jason-3 at NOAA,” Space News, September 22, 2014.

- Leonard David, “Profile: Thomas Berger, Director, Space Weather Prediction Center,” Space News, October 6, 2014; Jeff Foust, “Falcon 9 Ready for DSCOVR Launch, Landing Attempt,” Space News, February 7, 2015; Joe Kunches, “New satellite – DSCOVR – to monitor potentially damaging solar winds,” The Washington Post, February 10, 2015.

- Comments by Robert Smith to Dwayne Day, August 23, 2021.

- Dan Leone, “Clinton-era Deep Space Climate Observatory Ships to Florida Launch Site, Finally,” Space News, November 24, 2014; Jeff Foust, “DSCOVR Caught in Ripple Effect of Space Station Launch Delay,” Space News, December 29, 2014.

- Angela Fritz, “Stunning GIF shows moon crossing Earth from new satellite 1 million miles away,” The Washington Post, August 5, 2015; Rachel Feltman, “Why NASA’s new photos of the moon look super fake (even though they’re not),” The Washington Post, July 13, 2016.

- Dan Leone, “NOAA Space Weather Satellite Reaches Operational Orbit,” Space News, June 8, 2015.

- Jeff Foust, “Budget issues could delay space weather mission,” Space News, January 24, 2017.

- Dan Leone, “Loosely Defined Space Weather Program Has its Costs, Expert Says,” Space News, October 26, 2015; Jeff Foust, “Budget issues could delay space weather mission,” Space News, January 24, 2017.

- Steven Mufson, Jason Samenow, and Brady Dennis, “White House proposes steep budget cut to leading climate science agency,” The Washington Post, March 3, 2017; Jeff Foust, “White House budget proposal targets ARM, Earth science missions, education,” Space News, March 16, 2017; Jeff Foust, “White House seeks near-term cuts to NASA and NOAA programs,” Space News, March 28, 2017. The proposed cuts were reaffirmed two months later: Jeff Foust, “White House proposes $19.1 billion NASA budget, cuts Earth science and education,” Space News, May 23, 2017.

- Jeff Foust, “NASA plays down proposed Earth science cuts,” Space News, April 2, 2017; Caleb Henry, “Researchers bemoan limited space weather prediction capabilities,” Space News, April 6, 2017.

- Jeff Foust, “Senate follows House lead in criticizing NASA budget cuts,” Space News, June 30, 2017; Jeff Foust, “Senate restores funding for NASA Earth science and satellite servicing programs,” Space News, July 27, 2017.

- Jeff Foust, “NASA budget proposal seeks to cancel WFIRST,” Space News, February 12, 2018; Jeff Foust, “Senate bill restores funding for NASA science and technology demonstration missions,” Space News, June 12, 2018.

- Jeff Foust, “DSCOVR spacecraft in safe mode,” Space News, July 5, 2019.

- Ibid.

- Comments by Robert Smith to Dwayne Day, August 23, 2021; Jeff Foust, “Software fix planned to restore DSCOVR,” Space News, September 30, 2019.

- Jeff Foust, “NOAA warns of risks from relying on aging space weather missions,” Space News, February 19, 2020.

- Jeff Foust, “DSCOVR back in operation,” Space News, March 3, 2020.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.