The future of Mars science missionsby Jeff Foust

|

| “Mars sample return should be completed as soon as practically possible with no changes in its current design,” said Christensen. |

“Understanding the composition and the properties of either one would revolutionize our understanding of ice giant systems and solar system origins,” said Robin Canup of the Southwest Research Institute, one of the co-chairs of the decadal survey’s steering committee, at an April 19 event to unveil the report. She added that a Uranus mission won out over a Neptune orbiter because the Uranus mission could launch as soon as 2031 with no new technologies required.

The second-ranked flagship mission is an “orbilander” mission to Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus, which has a subsurface ocean that is potentially habitable. The mission, which would orbit the moon to sample its plumes before landing, beat our earlier concepts for a lander to Jupiter’s moon Europa because Enceladus has prominent, steady plumes that Europa lacks, and it lacks the strong radiation environment at Europa that would limit the lifetime of any lander there to weeks, versus years at Enceladus.

No Mars missions were among the finalists for the flagship missions studied by the decadal survey, unlike the previous decadal survey that backed a Mars rover sample-caching mission called MAX-C that became the Mars 2020 mission, whose Perseverance rover is collecting samples for later return to Earth. While the decadal survey endorsed the continuation of the Mars Sample Return (MSR) campaign, the report, and NASA’s actions, left many questions about the long-term future of NASA’s overall Mars exploration efforts.

Revising sample return

The decadal survey did endorse the MSR effort, calling it the “highest scientific priority” of NASA’s planetary science program. “Mars sample return should be completed as soon as practically possible with no changes in its current design,” said Phil Christensen of Arizona State University, the other co-chair of the decadal steering committee, at the rollout event.

The report provided a noteworthy data point about MSR: it estimates the cost of completing the effort of retrieving the samples and bringing them back to Earth at $5.3 billion. NASA had not disclosed a formal cost estimate for the effort, and that price tag is more than either the Uranus or Enceladus missions endorsed by the decadal.

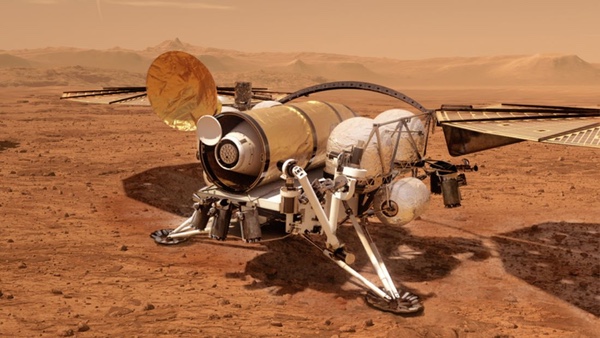

It’s unclear that cost reflects changes in the MSR effort. The previous plan called for three missions: the Perseverance rover to cache the samples, a sample retrieval lander to pick up the samples and launch them into Mars orbit, and an Earth return orbiter that would pick up the samples and return them to Earth. The lander and Earth return orbiter missions would launch in 2026, bringing the samples back in 2031.

However, in March, NASA announced a change in the structure of the MSR campaign. The single sample retrieval lander mission would be split into two landers, one carrying a European “fetch” rover to pick up the samples and the other the Mars Ascent Vehicle rocket that will launch the samples into orbit. Both are now scheduled for launch in 2028.

“The Phase A analysis demonstrated that, frankly, the single lander breaks entry, descent, and landing heritage. It is actually high risk,” Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA associate administrator for science, told a meeting of the National Academies’ Space Studies Board in March. A single lander would require a much larger aeroshell for entry into the Martin atmosphere, and in turn a larger payload fairing on the rocket launching it, than previous Mars missions.

Under the revised scenario, the Earth return orbiter, built by ESA, will launch in 2027, followed by the landers in 2028. That orbiter would bring the samples back in 2033. Zurbuchen didn’t discuss the cost implications of the revised Mars Sample Return architecture.

| “There’s a lot of angst in the community that MSR will grow and absorb other parts of the program, and we were trying to make the case that no, it’s a sound portfolio,” Christensen said. |

That revised schedule could pose complications for ESA, which is dealing with the delay of its ExoMars mission (see “The ending of an era in international space cooperation”, The Space Review, February 28, 2022). In a presentation last Tuesday at a meeting of the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG), Jorge Vago, ExoMars project scientist, said he believes it is unlikely that the mission could launch before 2028 given the work needed to replace the landing platform Russia had provided. Even a 2028 launch, he said, would likely require assistance from NASA for technologies such as landing thrusters and radioisotope heating units, which use small amounts of plutonium-238 to generate heat to keep the spacecraft warm.

That schedule would require ESA to prepare both the fetch rover for one of the sample return landers for launch in 2028, at the same time it (or NASA) launches ExoMars with the already-complete Rosalind Franklin rover, both a year after the launch of the ESA-led Earth return orbiter. Vago said that could mean considering “both MSR and ExoMars in sort of a holistic way, if you like, and see if we can find solutions that work for both missions.”

As for the cost of MSR, the decadal survey said that the campaign’s cost could increase by up to 20% without the overall Mars budget exceeding its historical share of NASA’s overall planetary science budget. “There’s a lot of angst in the community that MSR will grow and absorb other parts of the program, and we were trying to make the case that no, it’s a sound portfolio, it’s a diverse portfolio, and Mars makes up an appropriate percentage of that portfolio,” Christensen said at the MEPAG meeting last week.

If MSR’s cost grows beyond 20%, he added, NASA should seek a “budget augmentation” to cover those additional costs. “It cannot eat the lunch of the rest of the program.”

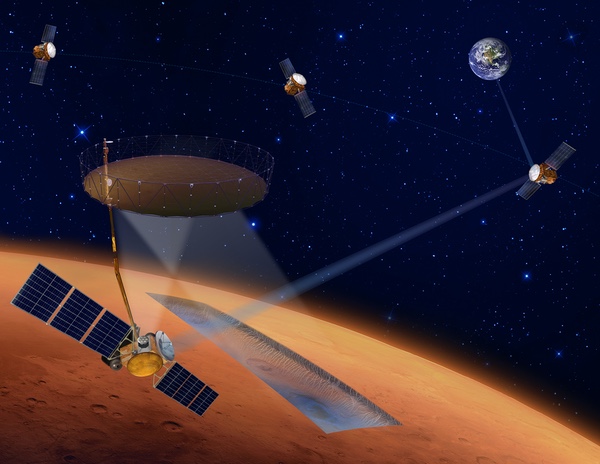

One proposal for the International Mars Ice Mapper mission combined the main spacecraft with its radar instrument with a network of data relay orbiters. (credit: NASA) |

Remapping an ice mapper

The decadal survey also addressed what had been the only other large Mars mission NASA had planned outside Mars Sample Return, an orbiter called the International Mars Ice Mapper, known as I-MIM or iMIM. That mission, scheduled for launch no earlier than 2026, would place a spacecraft into orbit equipped with a ground-penetrating radar to look for subsurface ice deposits that could be of interest to both scientists and those planning future human missions that could benefit from in situ resource utilization (ISRU).

The decadal expressed concern that the mission, as planned, would “only minimally address the science goals and measurement requirements for Mars ice mapping” as defined by scientists. “NASA should consider an implementation of iMIM that prepares for ISRU by humans and addresses the priority climate science questions at Mars related to near-surface ice,” it concluded (emphasis in original).

However, by the time the National Academies released the decadal survey, NASA had already moved to end I-MIM. The agency’s fiscal year 2023 budget proposed terminating NASA participation in the mission. “Due to the need to fund higher priorities, including to cover cost growth expected from the Mars Sample Return mission, the budget terminates NASA financial support for the Mars Ice Mapper,” NASA budget documents stated.

“We submitted the report assuming the Ice Mapper mission was a thing,” Christensen said during a presentation about the decadal survey at the MEPAG meeting last week. “We were strongly in favor of that mission. We had some suggestions in the report about how it could be improved.” As for NASA’s decision to end I-MIM? “We were surprised.”

| “It depends on what kind of advocacy there is,” Ianson said of the future of I-MIM. “It’s not as clear to me that a strong advocacy for Ice Mapper exists in Congress.” |

The I-MIM budget announcement came just before Mars scientists and spacecraft developers met at a conference in Pasadena, California, at the end of March on low-cost Mars mission concepts. I-MIM wasn’t necessarily a low-cost mission, although NASA’s contribution was relatively small as Canada was providing the radar instrument, Japan the spacecraft bus, and Italy and the Netherlands other key subsystems.

“The prime driver was overall stress on the budget for multiple projects,” said Eric Ianson, director of the Mars Exploration Program at NASA headquarters, at the conference. “It’s not unprecedented for the budget to propose a cut to a mission and then Congress puts it back in.”

However, he sounded skeptical that I-MIM could escape cancellation. “It depends on what kind of advocacy there is,” he said, describing successful efforts in recent years to restore funding for astrophysics and Earth science missions. “It’s not as clear to me that a strong advocacy for Ice Mapper exists in Congress.”

At last week’s MEPAG meeting, Ianson suggested I-MIM might live on without NASA, whose role in I-MIM had been limited to project management and launch. “We have had conversations with the international partners,” he said. “I know they are continuing discussion about the potential future of I-MIM.”

NASA’s decision came while a group of scientists is performing a study of the measurements that the mission could perform and how they can meet scientific and human exploration goals. The work of that measurement definition team continues, said its co-chair, Jeffrey Plaut, at the MEPAG meeting.

“Congress is just beginning this process of assessing this budget proposal from the president, and ultimately Congress will decide the appropriation,” he said. “No one is backing off from this mission other than what is in this proposed budget.”

A new lander to look for life

Mars was not included among the potential candidates for a flagship mission in the decadal, and was also left off the recommended list of destinations for NASA’s New Frontiers line of medium-sized missions.

However, the report did recommend NASA pursue a future Mars lander mission called Mars Life Explorer (MLE) similar in cost to a New Frontiers mission. “We decided it made more sense to have a strategic mission reside within the Mars Exploration Program,” Christensen said at the MEPAG meeting. Work on MLE would begin in earnest later this decade, after the peak spending on the Mars Sample Return campaign, for launch in the mid to late 2030s.

MLE at this point is primarily a concept for a mission designed to look for evidence of life on Mars. It and other medium-sized missions considered by the decadal “are existence proofs that the science objectives can be achieved in that cost cap,” said Amy Williams of the University of Florida at the MEPAG meeting.

The concept would involve a mission that would study ice deposits at the lowest latitudes possible, using a drill that would collect samples from up to two meters below the surface, studying them for biosignatures and assess the habitability of those deposits. “MLE is much more than a life detection mission,” she said, noting it would also be able to study geophysical properties of the near subsurface as well as the factors that create, preserve, and destroy ice deposits.

The mission, as conceived, would use a landing system like that proven by the InSight and Phoenix missions. That led some to wonder why the mission—estimated to cost $2.1 billion in an independent analysis by The Aerospace Corporation performed for the decadal—was so expensive. Williams said the suite of instruments is responsible for that higher cost.

| MLE and other medium-sized missions considered by the decadal “are existence proofs that the science objectives can be achieved in that cost cap,” said Williams. |

She added that the uncertain future of I-MIM, designed to map subsurface ice, shouldn’t affect MLE. “We never set up the assumption that we would require I-MIM data to do this,” she said, adding there was confidence among the team that worked on the concept that “we can select a landing site that meets these requirements.” In later discussion at MEPAG, though, some argued for having a rover or other mobility for the mission so it could probe more than just was in reach of the static lander.

The decadal was silent on other aspects of Mars exploration, including smaller science missions and preserving the aging fleet of Mars orbiters used for both science and communications relays. Christensen said the charge given to the decadal survey limited specific mission recommendations to larger missions; the decadal supported the smaller Discovery line of missions, for example, but did not recommend specific destinations or mission types for that program.

He said, though, he was aware of the growing interest in smaller Mars missions (see “A FAB approach to Mars exploration”, The Space Review, March 7, 2022) and thought they could fit into the overall Mars program. “If the MEP [Mars Exploration Program] exists and has a reasonable budget, then it’s really up to the MEP to decide if there should be smaller missions, and we think there’s a tremendous opportunity,” he said. “But, we didn’t think it was in our purview in discussing missions at those cost levels. We could be much more effective by advocating for an increase in the program and let the community figure out what’s the best design within that program.”

NASA is just starting its review of the planetary decadal. Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s planetary science division, said at the MEPAG meeting that she expected to have a “preliminary public response” in mid-July, or 90 days after the release of the report.

The Mars Exploration Program is also working on its own strategic plan, Ianson said at MEPAG. “This really has been the theme over the last six months or so,” he said, including a retreat the program held last December at JPL. That plan will incorporate the recommendations of the decadal survey and other reports as well as the workshop on low-cost Mars missions held in March.

“There are a lot of ideas that are out there, and what we want to try and do is put together a comprehensive program,” he said. NASA will start engaging with the Mars community once it has a framework of that plan, he said, but didn’t give a specific timeframe for that.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.