JWST and the future of large space telescopesby Jeff Foust

|

| “Scientists would love to have all three telescopes operating at the same time,” Gardner said of Hubble, JWST, and Roman. |

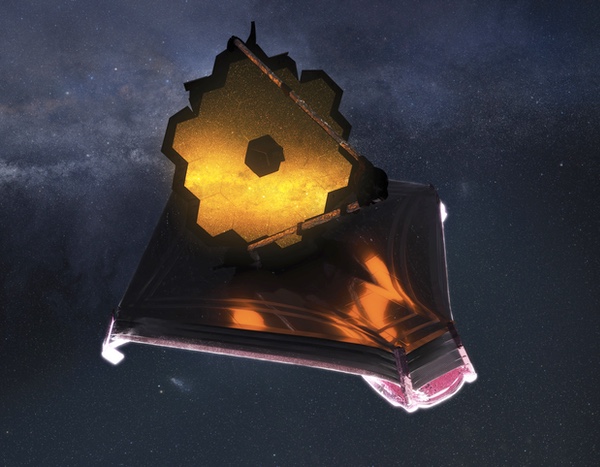

The release will mark the formal start of science operations of JWST, although the telescope has already completed some observations for astronomers beyond those being released Tuesday. It’s a day that astronomers have been anticipating for decades, waiting to use the large infrared telescope to probe the cosmos from objects in our solar system to the early universe, answering questions from the origin of the universe to the existence of habitable exoplanets. Those images and spectra will be flowing into scientists’ computers for up to 20 years, based on estimates of the supply of fuel needed to maintain its orbit around the Earth-Sun L-2 point.

But, even as JWST starts its scientific life, some astronomers are thinking about what comes after JWST.

In the near term, what comes after JWST is clear. NASA has been working for several years on the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, originally called the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope or WFIRST. That mission was the top priority of the 2010 astrophysics decadal survey devoted to studies of cosmology and exoplanets. The spacecraft is slated for launch in late 2026.

“Roman is a discovery machine. It maps very large areas of the sky,” said Jonathan Gardner, deputy senior project scientist for JWST at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, during a media briefing last month at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) about the upcoming JWST image release. JWST, by comparison, “goes deep on individual targets or smaller areas.”

JWST and Roman will overlap for many years, assuming Roman remains on schedule and JWST can achieve its two-decade lifetime. The venerable Hubble Space Telescope may still be in operation when Roman launches. “Scientists would love to have all three telescopes operating at the same time,” he said. “It would be a whole lot of fun to see the very rare extremes of the universe that Roman will discover and then look at them in the optical and ultraviolet with Hubble and in the infrared with Webb.”

| “I’m scared that the most ambitious priorities from Astro2020 become vaporware, little more than proposals for Astro2030, and we whiff the decade,” said Tremblay. |

In the longer term—after the end of JWST in the 2040s—there is a vision of a new generation of space observatories endorsed by the Astro2020 decadal survey published last November (see “A new approach to flagship space telescopes”, The Space Review, November 29, 2021.) They include a new large space telescope for ultraviolet, optical, and infrared observations and later space telescopes for X-ray and far infrared observations, collectively referred to as the new “Great Observatories” by astronomers.

The decadal, though, recommended a gradual approach to developing those future observatories, starting with a technology maturation program intended to retire technical risks and thus reduce the chances of the cost overruns and schedule delays that plagued JWST’s development.

NASA has taken those recommendations to heart. The publication of the Astro2020 decadal survey came too late to influence the agency’s fiscal year 2023 budget proposal released in March beyond a few minor tweaks. However, the agency is incorporating it into planning for the 2024 budget proposal. “The FY24 budget will be fully informed by the decadal survey,” said Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s astrophysics division, during a presentation at last month’s American Astronomical Society conference in Pasadena, California.

That includes, he said, support for studies of future large space telescopes. “Right now, we are in a three-stage process that will lead to beginning the next great observatory,” Hertz said. The first stage, now getting started, focuses on science and technologies studies to enable those future observatories, such as identifying technology “tall poles” that need to be addressed early in the development of those observatories. NASA is calling that effort the Great Observatories Mission and Technology Maturation Program, or GOMAP.

“The decadal survey spent a lot of pages explaining how we need to do more work up front than NASA has traditionally done in order to be prepared to deliver within cost and schedule commitments for very large projects,” he said in describing why NASA was embarking on GOMAP.

The second stage of the effort, which Hertz projected would begin in a few years, will involve trade studies and analysis of alternatives for proposed missions, starting with the observatory NASA is currently calling IROUV for infrared, optical, and ultraviolet observations. The third stage would be pre-formulation studies and a formal decision to proceed with IROUV, which would take a few more years.

That approach, while following the recommendations of the decadal, worries some astronomers. During a splinter session of the AAS conference devoted to the new Great Observatories, Grant Tremblay, an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, said what kept him up at night was that this gradual approach could be disrupted by changes in administrations or budget pressures from other parts of NASA, like Artemis or Mars Sample Return.

Thus, by the time work begins on the next astrophysics decadal survey, IROUV may have made little progress “and will be easy to relitigate” by the new decadal, he warned. “I’m scared that the most ambitious priorities from Astro2020 become vaporware, little more than proposals for Astro2030, and we whiff the decade.”

Others at the splinter session shared his concerns. “The point of this is to fly a mission,” said Bruce Macintosh of Stanford University. “Right now, with all due respect to all the priorities NASA is setting, precursor science is not on the critical path. The critical path is defining the science and mission trades.”

| Hertz argued that the top priority now for NASA’s astrophysics division is to keep Roman on schedule and within its budget. “Nothing less than the future of astrophysics depends on that,” he said. |

Going faster, though, introduces other challenges, such as funding. “Right now, we’re still commissioning the James Webb Space Telescope. Right now, we’re still building the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. And we have a budget of $1.6 billion,” Hertz said. “We have to be thoughtful about how we explain the need for another great observatory when we’ve got these two right now.”

He suggested that the experience of JWST would make it difficult for NASA to seek a budget increase to accelerate work on IROUV or any future flagship mission beyond Roman. “Unless NASA can show that we have learned lessons from the mistakes that were made in the management of the James Webb Space Telescope program and we can show that we can apply those lessons to another very expensive, very difficult great observatory, like the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, nobody will take us seriously.”

Hertz argued that the top priority for NASA’s astrophysics division, now that JWST is ready to begin operations, is to keep Roman on schedule and within its budget. “Nothing less than the future of astrophysics depends on that,” he said. Until then, “we would be at risk advocating to start the next thing because we would just get shut down.”

At the AAS splinter meeting, astronomers recognized the need to improve project management based on the lessons from JWST. “Project management is just as important for realizing a new science mission as any key technology,” said Aki Roberge of NASA Goddard. “There is more time and money to be saved by changing how we build ambitious missions than changing what we build.”

That’s where efforts like GOMAP come in. “It’s trying to take the habits of programmatically successful large mission and make them standard practice,” she said. “If we are to make the new Great Observatories fleet a reality, we need to do this.”

Astronomers also say they need supporters in Congress to enable future Great Observatories to move forward. “Building these things will be immensely complex, but the messaging needs to be really sharp and simple,” Tremblay said. He said the community needed a key backer in Congress, like former Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D-MD), who won support for JWST even as it faced potential termination because of cost and schedule problems.

He argued that messaging might involve geopolitics. “One of the biggest buttons you can push on Congress right now is saying that China is going to eat our lunch by 2050,” he said. “We are doomed to cede the future of discovery if we don’t start acting aggressively now.”

At the STScI briefing, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson took time to thank his former Senate colleague for her role in saving JWST. Mikulski “was able to come to the rescue” when JWST faced cancellation, he recalled. “So let’s give credit for where credit is due.”

Nelson and others at the briefing did not discuss finding new champions for NASA in general or future space observatories in particular. They did emphasize, though, how well JWST was performing since its launch. Despite all the problems in its development that drove up its cost to about $10 billion and delayed its launch by years, the observatory suffered no major issues during its deployment and commissioning and is operating better than expected.

Lee Feinberg, JWST optical telescope element manager at NASA Goddard, credited “attention to detail” by the team in its development. “We knew how significant this observatory is. This is the biggest, most complex science missions that NASA has ever built,” he said at the STScI briefing.

NASA has demonstrated with JWST that it can build an outstanding space telescope for a premium price, and the dazzling imagery to be released this week, and for years to come, may make many forget about the technical, programmatic, and political challenges it faced. But if NASA is to follow up on JWST and Roman with future Great Observatories, it will have to demonstrate a renewed attention to detail to not just technology but also program management.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.