Creating a Venus exploration programby Jeff Foust

|

| “Anything in the portfolio that is not confirmed right now is at risk,” Glaze said of NASA planetary missions. “We’re waiting to see what happens.” |

At a meeting November 28 of the Outer Planet Assessment Group (OPAG), Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s planetary science division, announced that the agency was delaying the launch of the Dragonfly mission to Saturn’s moon Titan by a year, to mid-2028. That, she said, was caused not by any issues with the mission itself but instead “incredibly large uncertainties” in potential budgets for planetary science in fiscal years 2024 and 2025.

At the same time, NASA is working to revise plans for the Mars Sample Return (MSR) program after an independent review in September concluded there was “a near zero probability” upcoming missions to take samples being collected by the Perseverance rover and bring them back to Earth would launch on schedule and budget. That review concluded the overall cost of MSR would be in the range of $8–11 billion, far higher than previous estimates.

NASA has since kicked off a reassessment of the overall MSR architecture, scheduled to be completed in March. In the meantime, NASA has slowed down work on MSR efforts, again citing budget uncertainty: a Senate bill would provide NASA with less than a third of the nearly $950 million requested for MSR, while a House spending bill would fully fund it.

Dragonfly and MSR are not the only planetary programs under the budgetary gun. NASA has delayed calls for proposals for future Discovery and New Frontiers missions. At OPAG, Glaze warned that missions in development that had not yet passed their confirmation reviews, where NASA sets the formal cost and schedule, could also face delays. “Anything in the portfolio that is not confirmed right now is at risk,” she said. “We’re waiting to see what happens.”

Venus scientists have already felt that pain. A year ago, NASA announced it was postponing work on VERITAS, one of two Discovery-class missions the agency selected in mid-2021 to go to Venus, by up to three years. NASA said the delay was needed to free up resources at JPL, the lead center for VERITAS, for the delayed Psyche asteroid mission and other priorities, like Europa Clipper (see “The hard truths of NASA’s planetary program”, The Space Review, March 20, 2023.)

At a meeting at the end of October of the Venus Exploration Analysis Group (VEXAG), the principal investigator for VERITAS, Sue Smrekar of JPL, made a case to limit that delay. The Psyche mission had launched, the payload for the NISAR Earth science mission had been shipped from JPL to India for launch preparations there, and Europa Clipper was making good progress for a launch next October, all reducing the workload at the lab. “Those issues are essentially behind us,” she said.

The problem now, she said, was not too much work but too little, particularly for people involved with synthetic aperture radars, one of the key instruments on VERITAS that will enable that orbiter to peer through the thick clouds of Venus. “There’s insufficient radar work at JPL. The radar workforce is really at threat,” she said. “It’s a really big technical threat for us.”

While NASA provided a small amount of funding for VERITAS to support its science team during the three-year delay, there was “zero support for engineering development” for the mission. Some engineers who had been working on VERITAS, Smrekar said, have had to leave to join other projects at JPL.

“Over the dozen years it took us to get selected we developed a highly experienced, knowledgeable team, and they have to go take other jobs,” she said.

The VERITAS team is studying, at NASA’s request, launch opportunities in 2031 and 2032, a delay of at least three years. However, she said it was still feasible to launch the mission as soon as November 2029 “if we get rolling in the next year.”

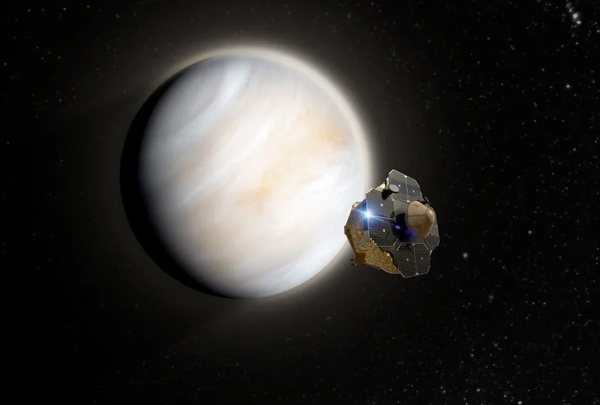

The next mission to Venus could be a privately developed one led by Rocket Lab and scheduled for launch as soon as the end of 2024. (credit: Rocket Lab) |

A Venusian strategy

Another reason for moving up VERITAS is to avoid conflicting with other Venus missions, Smrekar said. That includes fellow NASA mission DAVINCI and the European Space Agency’s EnVision mission, both slated to go to Venus in the early 2030s. Flying VERITAS before those two missions, she said, would free up resources and allow VERITAS to guide the planning for EnVision, also an orbiter mission, as originally projected.

| Smrekar said it was still feasible to launch VERITAS as soon as November 2029 “if we get rolling in the next year.” |

The next mission to go to Venus, though, may be a private one. In a talk at the VEXAG meeting, Christophe Mandy, lead system engineer for Rocket Lab’s interplanetary missions, said the company’s private mission to Venus, called Venus Life Finder, could launch as soon as the end of 2024.

That mission, being developed in cooperation with MIT and other organizations, would use the company’s Electron rocket to launch a spacecraft based on its Photon bus into Earth orbit. A series of orbit-raising maneuvers, followed by a lunar flyby, would send the spacecraft to Venus, arriving as soon as May 2025.

Once at Venus, the spacecraft would deploy a probe that would go into the planet’s atmosphere, collecting data using a single instrument designed to detect the presence of organic compounds in droplets in the planet’s clouds. That data collection would last for five minutes, after which the probe would transmit it back to Earth over the next 20 minutes before increasing temperatures and pressures overwhelm it.

Rocket Lab has not disclosed how much it is spending on Venus Life Finder, although Peter Beck, the CEO of the company, had previously described it as a “nights-and-weekends project” that is a lower priority than other projects.

It is also, in the case of Venus, a one-off effort for Rocket Lab. “Rocket Lab itself currently does not have any ambitions of funding other missions,” Mandy said at VEXAG. “We’re hoping that, by demonstrating that this is possible, we might be able to trigger more interest. The cost of this mission would be significantly lower than what is typical, so that might encourage governmental bodies to support this kind of mission.”

Venus scientists at the meeting, while intrigued by Venus Life Finder, don’t seem interested in one-off missions. Indeed, an emphasis at VEXAG was moving away from individual missions to a more coherent long-term strategy, modeled on what NASA has used for Mars exploration for more than two decades.

Scientists at the meeting released a draft white paper offering what it called a “Strategy for Venus Exploration.” The 17-page document takes as its starting point language in the most recent planetary science decadal survey published last year that called on NASA to “develop scientific exploration strategies, as it has for Mars, in areas of broad scientific importance, e.g., Venus.”

The document makes the scientific case for continued studies of Venus, noting there are “so many unanswered questions” about the planet’s atmosphere, surface, and interior that have relevance for many other aspects of solar system science and even exoplanets. “Venus serves as a cautionary tale when interpreting the limited information we have for large rocky exoplanets: at present, we can only tell if a terrestrial exoplanet is Earth-sized, not Earth-like, and a promising exo-Earth candidate could well turn out to be an exo-Venus.”

So many questions about Venus are unanswered, the report acknowledged, because of the difficulties operating spacecraft there, such as the high temperatures and pressures at the planet’s surface. The report calls for both more modest missions that can cope with those difficulties, like atmospheric probes and short-term landers, while working on technology to enable more ambitious surface missions. “The advent of long-duration, high-temperature systems will be game changing for Venus,” the report states (emphasis in original.)

| “Maybe we won’t see a Venus rover until the 2070s, but maybe if we don’t start talking about it now, it will never happen,” said Byrne. |

The report includes recommendations that advocates say could set the stage for a “Venus Exploration Program” at NASA much like the current Mars Exploration Program and its series of missions. “This document will set the stage, will lay the foundation for justifying NASA standing up a Venus Exploration Program in the 2030s,” said Paul Byrne of Washington University in St. Louis during a talk about the white paper at the VEXAG meeting.

That timing, he added, would coincide with missions currently in development that will arrive at Venus in the early 2030s, just as the next decadal is in development. “By the time that DAVINCI, VERITAS, and EnVision are returning their data, we have a group that’s ready to hit the ground running, so they’re clamoring for the establishment of a program.”

The document, still in draft form (a final version is expected to be ready by the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in March) got a warm reception at VEXAG, as participants debated issues ranging from international cooperation to communicating the importance of Venus exploration to the public: “making Venus sexy,” as one person put it.

While there’s limited clarity about when and how a Venus Exploration Program might be established, there is no lack of ambition. In his presentation, Byrne argued that such a program could eventually lead to rovers on the surface of Venus, much like those exploring Mars today.

“The scientific rationale for roving on Venus is just as compelling as it is for Mars. It’s just really, really, hard to do,” he said. “Maybe we won’t see a Venus rover until the 2070s, but maybe if we don’t start talking about it now, it will never happen.” It will be fodder for discussion, perhaps, for the next half-century of AGU Fall Meetings.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.