FARRAH, the superstar satelliteby Dwayne A. Day

|

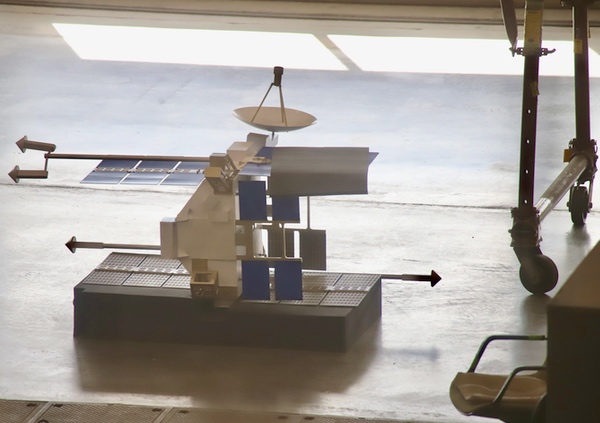

| Unlike Farrah Fawcett, whose poster reportedly sold six million copies, no previous images of a FARRAH satellite have been released, so this was the satellite’s first public, albeit low-key, debut, 42 years after it was launched. |

At least two and possibly up to five FARRAH satellites were built, starting in the early 1980s. They were among the last in the family of Program 989 satellites that operated in low Earth orbit and primarily detected signals emitted from Soviet ground-based radars. Program 989 started in the early 1960s under a different designation and satellites continued to operate probably until 2007, with about three dozen launched over 30 years. Most of the satellites were about the size of a large suitcase with multiple deployed antennas from their sides. They were ejected from other satellites soon after those satellites reached their operational orbits. The last few Program 989 satellites—possibly still using the FARRAH designation—were apparently much larger, shaped like tuna cans, and initially scheduled for launch from the Space Shuttle but later shifted to a few Titan II launches before the program ended in the early 1990s.

The number of P-989 satellites launched per year was never high, peaking at four in 1968 and another four in 1969. After that, the launches dropped significantly. There was one launched in 1971, two in 1972, one in 1973, two in 1974, and then one each in 1976, 1978, and 1979. The satellites had code names like MABELI, RAQUEL, and URSULA. (See “Big bird, little bird: chasing Soviet anti-ballistic missile radars in the 1960s,” The Space Review, December 14, 2020.) When first developed, they stored their collected signals on tape recorders and played them back over American ground stations. The data was analyzed over weeks or even months to determine the characteristics of Soviet radars. In the early 1970s, URSULA was modified to make it more useful to tactical forces, and the later satellites, such as FARRAH, incorporated a direct downlink capability so that they did not have to record their signals for later playback. Assuming a single satellite constellation, the satellites had a lifetime of at least two to three years by the late 1970s, but this apparently increased significantly with later satellites.

Snooping on signals

The FARRAH I satellite was launched in 1982, deployed off the side of a massive HEXAGON photo-reconnaissance satellite and boosted into a higher orbit with a small rocket motor. The satellite spun at greater than 50 revolutions per minute, sweeping its antennas across the face of the Earth. FARRAH II was deployed in 1984 off the side of the nineteenth HEXAGON satellite launched, the last HEXAGON to reach orbit. An official history indicated that FARRAH I was still operational by the mid-1990s after more than a decade in orbit, but amateur ground observers noted that both satellites maintained their rotation rates until 2007 and then started to slowly spin down until they stopped spinning entirely by 2011, implying that they were each operational for more than two decades. (See “Little Wizards: Signals intelligence satellites during the Cold War,” The Space Review, August 2, 2021.)

The exact missions performed by the FARRAH satellites are still classified, although by the late 1970s they were being used by the United States Army as part of a relatively new program known as TENCAP, for Tactical Exploitation of National CAPabilities. The specific Army program was known as the Tactical ELINT Processor/Tactical Unit Terminal system, or TEP/TUT, which had a unit logo featuring King Tutankhamun. TEP/TUT was a system mounted in vans and trailers that could be deployed with Army units in places such as West Germany and South Korea. FARRAH and other satellites could detect Soviet mobile air defense radar emitters. The mobile radars would guide vehicle-mounted missiles to shoot down American planes and helicopters. The satellite data would be processed by the ground system and distributed to Army commanders.

| The exact missions performed by the FARRAH satellites are still classified, although by the late 1970s they were being used by the United States Army as part of a relatively new program known as TENCAP. |

TENCAP was an increasingly expensive effort to bring “national level” intelligence collection systems that had previously served leaders such as the president, Pentagon, and intelligence officials, to directly support troops in the field. (See “From the sky to the mud: TENCAP and adapting national reconnaissance systems to tactical operations,” The Space Review, June 19, 2023.) FARRAH and similar satellites could fly over places such as Eastern Europe and nearly instantly provide useable intelligence to Army units in Germany.

RAQUEL, URSULA, and FARRAH were all named for actresses. Soon after Ronald Reagan became president, an official briefed him on American intelligence satellites. The person in charge of Program 989 was concerned that he would have to rename the satellites if Reagan objected—this would be expensive, because the names were included in computer programs. But when Reagan saw the names, he laughed and said that he knew those actresses, the names were fine.

The half-size FARRAH model in the Udvar-Hazy restoration hangar looks similar to photos of the earlier URSULA satellites deployed during the 1970s, with some apparent changes to the antenna configuration. When the Smithsonian’s downtown Washington National Air and Space Museum fully reopens in a few years, the FARRAH model will go on display.

This poster adorned the wall of many American teenage boys in the 1970s, becoming the best-selling poster of all time. It also inspired somebody in the National Reconnaissance Office to name a satellite after Farrah Fawcett. |

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.