Whither Starliner?by Jeff Foust

|

| “For me, one of the really important factors is that we just don’t know how much we can use the thrusters on the way back home before we encounter a problem,” said Bowersox. |

The landing concluded the Crew Flight Test (CFT) mission for Starliner, but when technicians opened Starliner’s side hatch after landing, there was no crew inside. NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams, who launched on Starliner in early June, remained on the International Space Station, spectators to the spacecraft’s return rather than participants.

Nearly two weeks earlier, NASA made the decision to keep the astronauts on the ISS, one that became increasingly likely as the weeks wore on without a resolution to the thruster problems Starliner experienced on its approach to the station (see “Starliner’s uncertain future”, The Space Review, August 12, 2024). Agency leadership decided August 24 to fly Starliner back without a crew, requiring Wilmore and Williams to extend their stay on the ISS through the Crew-9 mission early next year. (A side effect of the decision is removing two astronauts assigned to Crew-9, Zena Cardman and Stephanie Wilson, less than a month before launch to free up seats for Williams and Wilmore,)

Officials said at a briefing announcing the decision that, despites weeks of thruster testing and work on models of the thrusters, they still could not fully understand what was causing thrust levels to drop. “That uncertainty remains in our understanding in the physics going on in the thrusters,” said Jim Free, NASA associate administrator.

The tests had shown that a Teflon component in the reaction control system (RCS) thrusters was heating up, calling it to swell and extrude, blocking the flow of propellant. What was not clear to engineers, though, was how much use of the thrusters would cause a loss of performance, a concern during critical phases of flight like the deorbit burn, where the RCS thrusters maintain attitude control while larger thrusters perform the actual burn.

“For me, one of the really important factors is that we just don’t know how much we can use the thrusters on the way back home before we encounter a problem,” said Ken Bowersox, NASA associate administrator for space operations, at the briefing.

Those discussions among NASA and Boeing personnel took place amid heightened concerns about safety and avoiding a repeat of Challenger and Columbia, when dissenting views were ignored or never expressed.

“I’ve been very hyper-focused lately on this concept of combating organizational silence,” said Russ DeLoach, chief of NASA’s Office of Safety and Mission Assurance, at a briefing a week and a half before the decision. “I recognize that may mean at times we don’t move very fast because we’re getting everything out, and I think you see that at play here.”

At the time there were rumors of heated debates and even formal dissents, but NASA officials said at the earlier briefing that there was no consensus yet about what to do with Starliner and thus nothing to dissent. “It really was, ‘Do you feel like you have all the data you would need now to make a good decision?’” DeLoach recalled. “To me, most people were at, ‘No, we need a little more work.’”

After NASA made the decision to bring back Starliner uncrewed, agency officials said the debates were not nearly as strident as some claimed, with the decision for the uncrewed return being unanimous. “I would not characterize it as heated,” said Steve Stich, NASA commercial crew program manager, at a briefing last week, although he noted there was “some tension in the room” in those discussions. “I wouldn’t say it was a yelling screaming kind of meeting. It was a tense technical discussion.”

After all that, Starliner’s return was almost anticlimactic. The spacecraft undocked from the station at 6:04 pm EDT Friday and swiftly moved away from the ISS, a change from previous procedures intended to simplify the spacecraft’s departure. The spacecraft later executed its deorbit burn and made what Stich called a “bullseye landing” at White Sands.

That return was not without problems. Stich said that two RCS thrusters got hotter than expected during the deorbit burn, but continued to function. Stich said that software that would have turned off malfunctioning thrusters had been disabled for Starliner’s return, but didn’t immediately know if that software would have otherwise turned off the thrusters.

| “He expressed to me an intention that they will continue to work the problems once Starliner is back safely,” Nelson said of Boeing’s CEO. |

A separate thruster on the crew capsule, one of 12, also malfunctioned, but Stich noted it was of a different design than those on the service module, using a monopropellant and catalyst bed rather than the bipropellant design of the RCS thrusters on the service module. However, a redundant thruster meant no loss of performance for the capsule. A navigation computer struggled to get a lock of GPS signals after emerging from the blackout caused by the plasma created during reentry.

None of those problems would have prevented a safe return for Williams and Wilmore, but agency officials said they had no regrets about their earlier decision to leave them on the station. “I think we made the right decision to not have Butch and Suni on board,” Stich said after landing. “It’s awfully hard for the team, it’s hard for me, to sit here and have a successful landing and be in that position, but it was a test flight and we didn’t have confidence in the certainty of the thruster performance.”

Inside the Starliner crew cabin, a Crew Flight Test patch ang signatures of NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams, who remain on the space station. (credit: NASA/Aubrey Gemignani) |

Boeing’s silence and the path to Starliner-1

Notably absent from the discussions about Starliner’s return was Boeing. The company, which had been included in earlier NASA updates about the CFT mission, had not participated in any NASA briefings since late July. The company’s own “Starliner Updates” website was not updated after an August 2 post where the company declared its confidence in the spacecraft until the actual uncrewed return of Starliner Friday night.

That was supposed to change with the post-landing briefing late Friday night, with two company executives— John Shannon, vice president of Boeing Exploration Systems, and Mark Nappi, Boeing vice president and commercial crew program manager—originally scheduled to participate. But those in the briefing room at the Johnson Space Center noted that shortly before the press conference was scheduled to start, the two chairs reserved for the Boeing executives were removed.

“We talked to Boeing. They said, ‘Hey, we’d like NASA to take the press brief.’ They deferred to us,” Joel Montalbano, NASA deputy associate administrator for space operations, said at the briefing when asked about their absence. Those executives were present for the landing at mission control, he added, and spoke with NASA officials after the successful landing. “Boeing is committed to continue their work with us,” he said.

At the August 24 briefing to announce the decision to return Starliner without a crew, NASA administrator Bill Nelson said he spoke with Boeing’s new CEO, Kelly Ortberg, after the agency’s decision. “He expressed to me an intention that they will continue to work the problems once Starliner is back safely,” Nelson said. Asked later in the briefing how confident he was that Starliner would carry astronaut again, he simply replied, “100%.”

However, Ortberg, along with other Boeing executives, have remained quiet publicly about Starliner’s future. After landing, the company released a brief statement, attributed to Nappi: “I want to recognize the work the Starliner teams did to ensure a successful and safe undocking, deorbit, re-entry and landing. We will review the data and determine the next steps for the program.”

Boeing has already taken $1.6 billion in charges against the Starliner program to date, including $125 million in the second quarter this year. That is only likely to grow as the company works to correct the thruster problems and helium leaks Starliner suffered on CFT.

| “We’re going to take our time to figure out what we need to do to go fly Starliner-1,” Stich said. “It’s probably too early to think about what the next flight looks like.” |

The assumption many in the industry had was that Boeing would have to conduct another test flight, with or without astronauts on board, to demonstrate those problems had been corrected before NASA would certify the vehicle and allow regular crew rotations to begin, starting with a mission designated Starliner-1. That mission is currently planned for no earlier than next August, although NASA is hedging its bets by preparing another SpaceX Crew Dragon mission, Crew-11, in parallel with Starliner-1.

At the post-landing briefing, though, NASA officials suggested Boeing might be able to win certification and proceed directly to Starliner-1 without the expense of another test flight. Stich, for example, discussed the work ahead to replace seals that likely caused the helium leaks, as well as changes to how thrusters are used. “That’s the path to Starliner-1,” he said.

Even without returning with astronauts on board, he estimates that the CFT mission met 85% to 90% of its objectives. “We’re going to take our time to figure out what we need to do to go fly Starliner-1,” he said. “It’s probably too early to think about what the next flight looks like.”

Earlier last week, Stich said it was possible that the thruster issues could be resolved without modifying the thrusters themselves. Instead, NASA and Boeing were looking at ways to modify how they are used to reduce heating that caused the degradation in performance.

“We know the thrusters are working well when we don’t command them in a manner that overheats them and gets the poppet to swell,” he said, referring to the component that was restricting the flow of propellant. That could include, he said, changes to the structures called “doghouses” on the service module that host the thrusters to reduce the heat buildup inside them.

That will take some time to figure out, he noted. “We’ve been entirely focused this summer on understanding what is happening on orbit, trying to decide if we could bring the crew back or not,” Stich said. “What we need to do now is really lay out the overall plan, which we have not had time to do.”

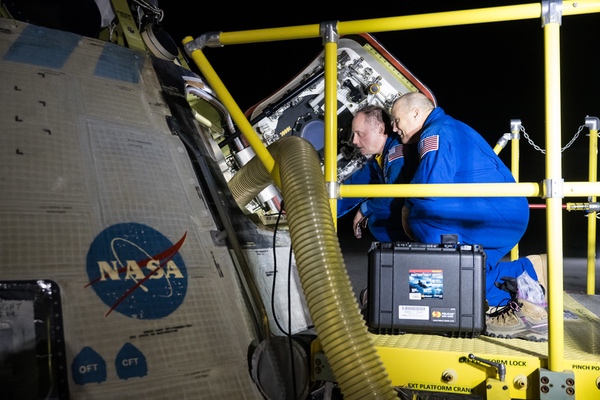

NASA astronauts Mike Fincke (left) and Scott Tingle look inside Starliner after landing. Both are assigned to Starliner-1, the first operational Starliner mission to the ISS. (credit: NASA/Aubrey Gemignani) |

A decade of commercial crew development

Starliner’s uncrewed return comes almost exactly a decade after NASA issued contracts for the development of that spacecraft and SpaceX’s Crew Dragon. In mid-September 2014, NASA announced it selected the two companies for Commercial Crew Transportation Capability, or CCtCap, contracts to cover the final development of the spacecraft as well as uncrewed and crewed test flights. Boeing’s contract was worth $4.2 billion while SpaceX’s came in at $2.6 billion (see “Commercial crew and commercial engines”, The Space Review, September 22, 2014.)

| “From a commercial standpoint, we have two crew vehicles,” said Montalbano. “Is it slower than what we expected? Absolutely. It is slower, but we’re making progress.” |

A decade later, the two CCtCap companies are in very different positions. Crew Dragon has become the kind of success that NASA dreamed of for commercial crew. After a successful crewed test flight to the ISS in the summer of 2020, Crew Dragon has now flown eight crew rotation missions to the ISS, ending NASA’s reliance on Russia’ Soyuz (although NASA and Roscosmos still swap seats between the spacecraft for operational purposes.)

In addition, Crew Dragon has won additional business. It has flown four private astronaut missions, three to the ISS for Axiom Space and a standalone mission, Inspiration4. By the end of this month, SpaceX may have two more Crew Dragon launches under its belt: the Crew-9 mission for NASA and the Polaris Dawn private astronaut mission (see “Polaris’s dawn”, The Space Review, September 3, 2014.)

Boeing, by contrast, is clearly struggling. CFT launched four years after SpaceX’s Demo-2 and, unlike that earlier mission, could not bring its astronauts back. It is increasingly unclear if Boeing will be able to fly the six crew rotation missions available under its CCtCap contract before the ISS is retired around the end of the decade, and the company has not announced any commercial deals for Starliner other than potential participation in the Orbital Reef space station.

So does NASA feel that the commercial crew program, with that mixed bag, has been a success? NASA officials at the post-landing briefing late Friday night weren’t particularly reflective, perhaps because of concentrating on the specifics of getting Starliner back over the last several weeks.

“From a commercial standpoint, we have two crew vehicles,” said Montalbano. “Is it slower than what we expected? Absolutely. It is slower, but we’re making progress.”

“I would say we've done a great job at fielding two transportation systems in fairly record time,” said Stich. “You’re starting to see that market get fostered with non-NASA missions, which is what we want.”

“When we started, it was kind of an experiment,” he added of the commercial crew program. “But now, we’re starting to see the benefits of the investments by both NASA and our partners.” Those benefits, like the achievements of the companies, remain unequally distributed, with long-term implications for NASA and the broader space industry.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.