Surveyor sample return: the mission that never wasby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Surveyor was dramatically de-scoped by the mid-1960s, both in goals and numbers. But before this happened, NASA allowed its scientists and contractors to think big. |

In 1960, James was sent to GM’s industrial facility in Indianapolis to work on a joint proposal with RCA in response to a NASA request to develop the Surveyor Lunar Soft Lander. But after working a short time on the proposal, RCA decided to pull out of the project. GM, lacking a partner, also decided to “no-bid” on the proposal. James thought that his short foray into aerospace was over. In early 1961, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, evaluated industry proposals for Surveyor and selected Hughes Aircraft to develop the lander. Surveyor had a dry mass of approximately 300 kilograms, making it a lightweight compared to Firefly’s Blue Ghost 1 lander, which masses 490 kilograms. However, at the time there was no rocket capable of sending Surveyor’s mass to the Moon, and thus launch vehicle technology had to be pushed to make even a simple Surveyor lander possible.

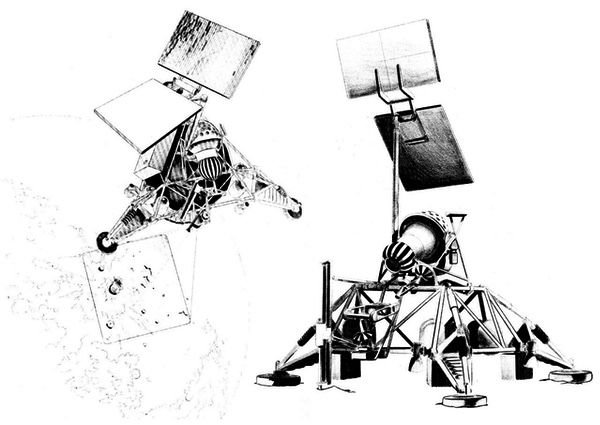

Hughes Aircraft Company won the contract to develop the Surveyor lander in early 1961. The initial plans for Surveyor were ambitious, including a variety of instruments including a drill. Surveyor was scaled back to primarily support the Apollo program. GM dropped out of the bidding for Surveyor after losing its partner, RCA. (credit: Hughes Aircraft Company) |

Surveyor sample return

In 1961, GM established a Defense Systems Division (DSD) in Goleta, California, near Santa Barbara. Some engineers left RCA to go work for the new GM division, and one of its first projects was proposing mobile missile launchers disguised as moving vans that would travel around American highways to evade Soviet detection and attack. James went from Detroit to southern California to temporarily work for DSD before returning home.

In early 1961, James was told that GM was going to submit an unsolicited proposal to NASA for a Lunar Sample Return mission based upon Surveyor. He was asked to produce artwork for the proposal and did so, including a color tempera illustration of the vehicle firing its sample return module back towards Earth.

NASA liked GM’s proposal, although it is unclear if the agency gave GM money to further study it or if GM continued on its own. By October 1961, GM’s DSD began work on a more detailed Surveyor sample return proposal. James again traveled to Goleta from Detroit to work on the project. When he arrived, he learned that DSD was already doing substantial research work to try and understand the lunar surface. This consisted of developing various analogues for the lunar regolith (i.e. dirt) and firing projectiles into them to try to understand how meteorite impacts would affect the material. They had no actual data about the lunar surface and ended up assuming that the soil would most likely be volcanic in nature.

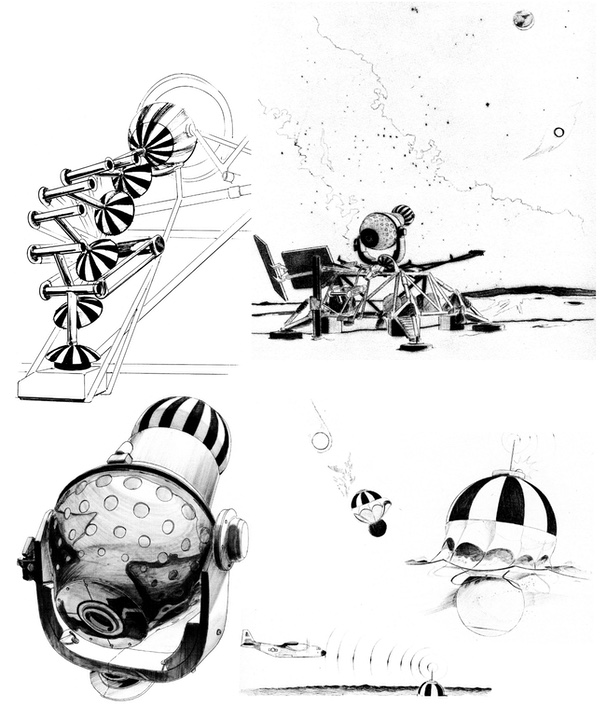

When James began work on the sample return project, he discovered that it was essentially the same as the company’s earlier proposal, but the engineers were working on a much more detailed concept. “The heart of the system was a spherical solid rocket motor coupled to the basketball-sized payload return module,” he wrote. “The two spheres would be connected in flight by a short cylinder housing the flight trajectory and communications electronics. The completed vehicle would look very much like a snowman. The payload sphere, once separated, would be the only part to survive earth reentry. Because it was spherical, it didn’t need an attitude control system and its whole surface would be ablative to project the contents from the heat of reentry.”

Although James did not say so, DSD’s engineers must have had some information on Hughes’ Surveyor work, because he started producing illustrations based upon a vehicle that looked like Hughes’ design, with three landing legs and two big solar panels mounted atop a mast.

GM’s lunar sample return proposal included mechanisms for transporting a drill sample as well film cassettes from one or more cameras to the Earth return vehicle. The return vehicle would be launched directly back to Earth and splash down in the ocean for recovery. The proposal was not accepted for development, and Surveyor was scaled back from its ambitious origins. (credit: Norman J. James via GM Media Archive) |

The return payload would be complicated. It needed to not only bring back lunar samples but also film from one or more cameras. During descent to the lunar surface, the Surveyor would take photos of the landing zone to assist in identifying the site. The photos would use film that would be stored in a cassette. Additional photos would be taken on the surface. Because the camera would be located perhaps half a meter or more from the return vehicle, the film cassette would have to be transported to the payload module. The lunar samples would be obtained with a drill and would also have to be transferred to the return module.

| Surveyor was a troubled program for some time due to poor organization at Hughes. NASA also dramatically redirected Surveyor from a scientific program to a much narrower focus on measuring the surface characteristics of the Moon to enable safe landing of Apollo Lunar Modules. |

“With everything loaded, a cover would close and secure the materials in the return module. The snowman, mounted within a gimbaled basket, would then be aligned to its launch attitude, spun up for spin stabilization, and the rocket ignited for its return to earth. The return trajectory would place reentry over the Pacific Ocean,” James wrote. “Upon reentry, drag from Earth’s atmosphere would convert velocity into heat, the surface of the tumbling sphere would burn and char. Embers would then break free, taking away excess heat before it could migrate inward. The rocket motor and electronics modules, being separated, would be consumed in the upper atmosphere. At a set altitude, a small para-balloon (parachute/balloon) would deploy to reduce the impact velocity as it hit the water. It would then discharge a yellow dye marker and transmit a homing signal to help the recovery team find it.”

James worked with the engineering team designing hardware and creating technical illustrations for the proposal. “On Surveyor, the snowman return vehicle and its launch platform would be stacked on top of the soft-lander’s triangular truss architecture.” If they mounted the snowman horizontally it would make it easier to design the mechanisms for transferring film cassettes and soil samples. But this would result in greater landing loads and shocks to the system compared to mounting the snowman vertically.

When the sample return proposal entered a technical and cost estimating phase, James went to work on a GM proposal for large lunar roving vehicles. Over the next several years he would work on several lunar vehicle proposals, including one for the Surveyor.

Failure to launch

In his book, James did not explain what happened to GM’s Surveyor Lunar Sample Return proposal. However, it was clearly not pursued and this author has found no reference to it in NASA Surveyor documentation, which is admittedly sparse. Surveyor was a troubled program for some time due to poor organization at Hughes. NASA also dramatically redirected Surveyor from a scientific program to a much narrower focus on measuring the surface characteristics of the Moon to enable safe landing of Apollo Lunar Modules. The program was cut back in size several times as the costs of Apollo mounted. Early illustrations of Surveyor show it equipped with a variety of instruments such as a drill. These were soon eliminated, although even if they had been pursued, problems with the mass of the vehicle and the limitations of its launcher might have resulted in their eventual cancellation.

James’ book provides an interesting lesson to space historians that previously unknown information can be found in unusual places, such as the memoirs of a car designer. Surveyor is now all but forgotten in the early days of space history, but perhaps there is more to be learned about it.

Next: Hotrodding on the Moon.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.