Stars in the sky: The top secret URSALA, RAQUEL, and FARRAH satellites from the 1970s to the 21st centuryby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Satellites with names like URSALA, RAQUEL, FARRAH, GLORIA, and CARRIE have only recently been declassified, with significant information about them released only in the past two months, including the disclosure of previously secret space shuttle payloads. |

For the first decade, the various satellites under this program chased whatever new ELINT targets appeared and were of interest to the intelligence community. The satellites were designed to be inexpensive and simple enough to be developed in a year or less in response to new threats. Their payloads were often bespoke designs, built only once or twice before they were replaced by something else.

But by the 1970s, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), which managed the program, began to standardize the satellites and give them an operational mission supporting military forces around the world. Satellites with names like URSALA, RAQUEL, FARRAH, GLORIA, and CARRIE have only recently been declassified, with significant information about them released only in the past two months, including the disclosure of previously secret space shuttle payloads. These satellites represented a profound change in the collection of intelligence data from orbit, a change from serving relatively exclusive “national” leadership to supporting tactical forces of the Army, Navy, and Air Force. They brought the wizard war of space-based electronic intelligence to the warfighter.

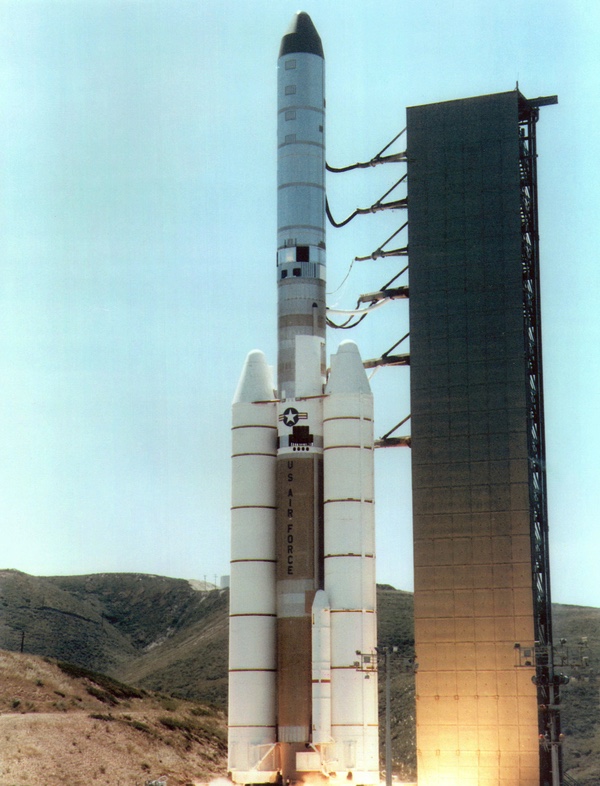

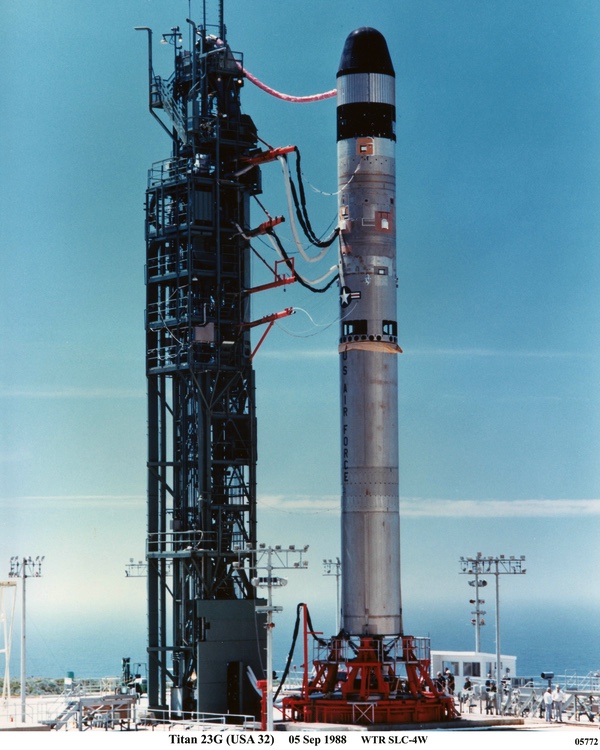

During the 1970s and 1980s, subsatellites were deployed off the sides of large HEXAGON photo-reconnaissance satellites. (credit: NRO) |

Program 989 and Mission 7300

The first of the small satellites were colloquially called “hitchhikers,” but Lockheed Missiles and Space Company, which built them, referred to them as Program 11, or P-11 satellites, and this designation seems to have been used by officials throughout the 1960s and 1970s as generic shorthand for the small satellites, even when they had official program designations and specific names. In 1965/66, the P-11 program was redesignated P-770B, then Program 989.[1] However, as fewer individual satellites were procured over the years, it appears from available documentation that officials often referred to the individual satellites rather than the program they were part of. The Program 989 satellites continued flying even after a larger series of signals intelligence (SIGINT) satellites known as Program 770 ended with the last launch in 1972.[2]

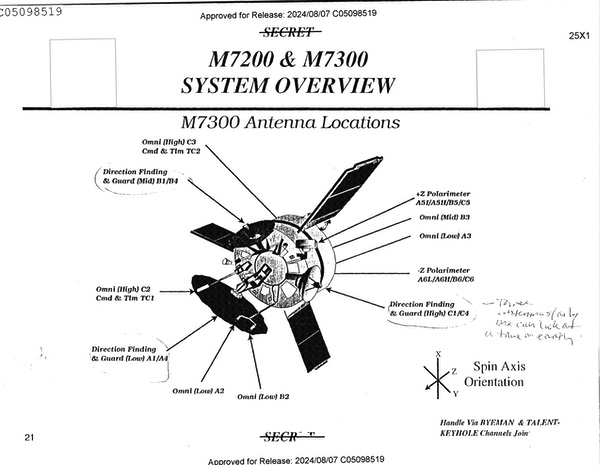

By the 1970s, the intelligence community began using the TALENT-KEYHOLE designation “Mission 7300” to refer to the collection of radar signals and their geolocation data by these low Earth orbit satellites. Mission 7100 referred to the ocean surveillance mission performed by the PARCAE satellites. Mission 7200 referred to payloads hosted on other satellites, such as the AFTRACK electronic intelligence systems carried on many CORONA satellites in the 1960s.[3] By the 1980s there was increasing discussion within the intelligence community of merging both Missions 7100 and 7300 by developing new satellites incorporating both of their capabilities.

During the 1960s, the satellites often lasted only a few months in orbit. Their lifetimes were often limited by their low orbits. Satellites with large antennas, such as large low-frequency spiral antennas or large flex-rib dish antennas, were dragged down by the thin atmosphere at their altitudes. It was typical for satellites to last one to four years before they burned up in the atmosphere, although MABELI was still operating when it burned up after seven years and TOP HAT II was still functioning when it burned up at six years.[4] The Secretary of the Air Force Special Projects office, located in Los Angeles, was the NRO’s West Coast organization responsible for managing Mission 7300, among other projects. Usually only referred to as SAFSP and mostly manned by Air Force officers, SAFSP sought to increase the lifetimes and capabilities of the satellites so that fewer were required to perform the missions. Improved electronics made this possible.[5]

Throughout the 1960s the satellites had names like PUNDIT, SAVANT, SOUSEA, and SAMPAN that were obscure references to people working in the intelligence field, or sometimes even inside jokes or puns. The program managers (all men) were told that they needed to avoid possible hints about the satellites’ missions, and so they decided to name them after movie actresses.[6]

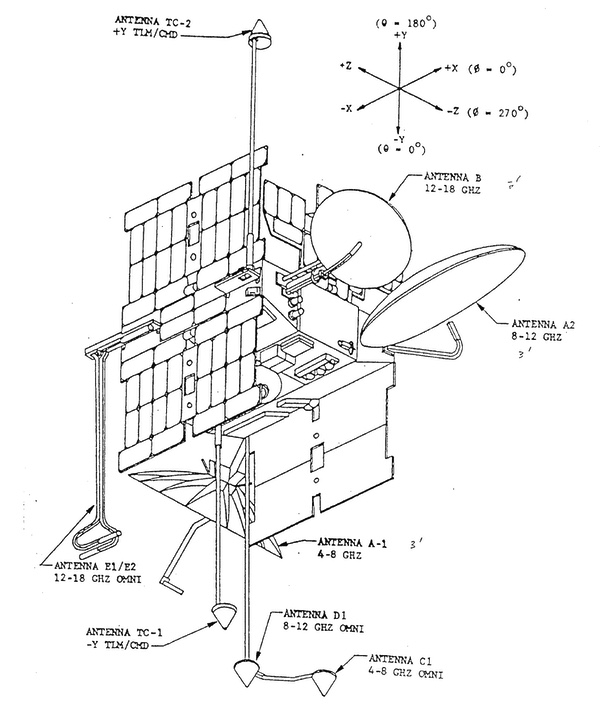

Because the P-11s were carried into orbit alongside other, bigger, photo-reconnaissance satellites, the satellites were inevitably compromises. They were limited in size, mass, power, capability, and cost. Nevertheless, they were designed to pack as much capability into a small size as possible. They were notable for sporting several dishes around their periphery, most of which were spring-loaded to deploy using centrifugal force.

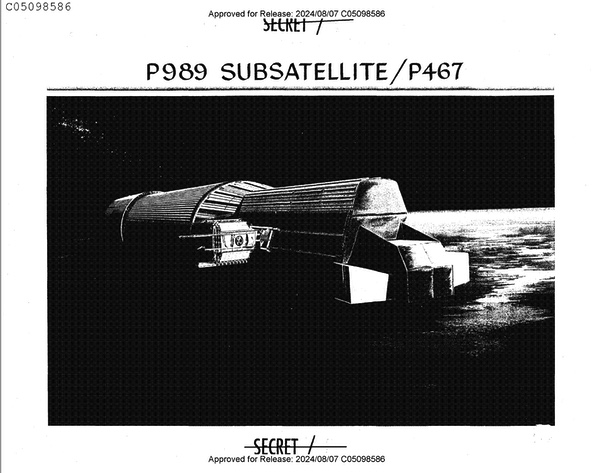

Radars produce mainbeams and weaker sidelobes. The Program 989 satellites usually had the ability to detect both, and in some cases they could determine fine-grain data about the signals, enabling the development of jamming and spoofing capabilities. (credit: NRO) |

Radars produce main beams that radiate forward of the emitter, and side lobes that spread out to the emitter’s sides. The main beam is obviously the most powerful part of the emission, but it is focused in a specific direction and can only be intercepted if a collector such as a satellite antenna travels through the emission cone. The side lobes spread out over a much larger area but are fainter. A satellite with parabolic dishes can collect the fainter side lobes, whereas main beams can be collected in low Earth orbit without large dish antennas if the satellite travels through them. Thus, even though the Program 989/Mission 7300 satellites were not particularly large, their dish antennas provided a capability for intercepting faint, and more prolific, radar side lobes.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the NRO was also launching several new classes of larger signals intelligence satellites to much higher orbits, including geosynchronous orbits. Those satellites were designed to collect Soviet microwave communications, missile and rocket telemetry, and other signals. But they were primarily restricted to northern hemisphere targets, for the satellites in highly elliptical orbits, and to eastern hemisphere targets if they were located in geosynchronous orbit over the eastern hemisphere. In other words, a signals intelligence satellite located in the eastern hemisphere to monitor communications from Moscow could not also cover targets over Central America. Program 989 low Earth orbiting satellites were still necessary for intercepting radar signals in large part because the satellites were closer to their targets and covered the entire globe from their polar orbits. The low Earth orbiting satellites also could serve new users, not just the Central Intelligence Agency and National Security Agency and the “national” level customers of their intelligence like the White House and senior military leadership.

Four URSALA satellites were launched during the 1970s. The ability of URSALA to provide data to mobile electronics vans deployed in the field made these satellites valuable for tactical users. Tactical Exploitation of National CAPabilities (TENCAP) became an important intelligence mission. (credit: NRO) |

URSALA and the dawn of TENCAP

The Vietnam War played an important part in causing a redirection in the low Earth orbit signals intelligence program. In the mid to late 1960s, the NRO had launched more than a dozen P-11 satellites designed to intercept anti-ballistic missile (ABM) radar signals. But by 1969, hundreds of American aircraft had been shot down by missiles over Vietnam, and for several years overhead imagery had detected a Soviet radar system deployed in the field, but no electronic intercepts had been made (the identity of this radar is still deleted from declassified documents.) In addition, the existing satellites lacked the capability to search for Ku-band emitters in the 12-to-18-gigahertz range. Finally, radar experts expected the Soviet Union to begin deploying “double-agile radars” that could simultaneously frequency hop from pulse-to-pulse and jitter in pulse repetition interval (the time between pulses) from pulse-to-pulse. A new capability would be required to detect these emerging radar threats.[7]

The lack of specific knowledge about these emerging high-threat signals produced a set of requirements that could not be satisfied by a single system using the technology available at the time but led to the creation of two new satellite systems: URSALA and RAQUEL.

| “Back in the early 1970’s the new mission was to get data directly to the commander on the FEBA (Forward Edge of the Battle Area). I had a payload with possibilities if it could be ‘trailerized.’ We decided to go for it but needed a catchy name, so we used DRACULA…Direct Readout and Collection ULA (‘ULA’ was the three-letter shorthand for the URSALA payload).” |

URSALA was designed to collect signals from double-agile radars in bands from 2 to 12 gigahertz. It searched radar side lobes, not their main beams. It was considered a “general search” system. RAQUEL was designed not to search from horizon-to-horizon, but to maximize the intercept time on relatively short slant range targets by using a spinning pencil beam (i.e. the narrow beam in which a signal could be detected by the satellite.)[8]: “Since the frequency of the signals was not known, it was necessary to develop a collection system capable of searching a wide frequency range. A means of associating the signals definitely with the [radar] was also required, as was a capability to measure technical parameters precisely.” The RAQUEL satellites required more time to develop than URSALA due to their increased complexity.[9]

Four URSALA satellites were deployed from HEXAGON photo-reconnaissance satellites during the 1970s. They were placed into approximately 509-kilometer (275-nautical-mile) circular orbits. They were designed to detect pulsed emitters primarily within the Soviet Union. URSALA represented a change in design philosophy for the NRO: rather than the custom approach that was used for many of the dozens of satellites produced during the 1960s, SAFSP sought to standardize the satellites and their payloads. URSALA satellites also had some ability to detect and geolocate ships at sea, although this was not a primary mission.

URSALA I and II were launched in 1972 and 1973 and designed for general search and electronic order of battle for pulsed and continuous wave emitters with a frequency range of 2 to 12 gigahertz. They weighed 178 kilograms (393 pounds) and had nine-month design lifetimes. URSALA I ultimately lasted 70 months, and URSALA II lasted 61 months.[10]

Although URSALA (and later RAQUEL) was intended to detect signals from surface-to-air missile radars that were deployed tactically, at least at first the satellites were serving national intelligence requirements, meaning that their data was evaluated in places like the National Security Agency, and then eventually used to better protect tactical aircraft. Tactical forces would indirectly benefit from the intelligence, but they would not receive it.

However, the 1973 war in the Middle East prompted the use of the satellites for “operational support,” and the success of the URSALA I and II satellites in this role stimulated the development of techniques for more rapid data processing, both on the satellites and on mobile ground terminals.[11] This was apparently the beginning of a new mission for these small satellites, the evolution from their use primarily in support of strategic intelligence gathering to providing data that could be directly used by military forces deployed around the world—electronic intelligence order of battle (EOB), or an indication of the types and locations of enemy deployed electronic emitters. For instance, detecting Soviet SA-6 mobile surface to air missile radars in a new location provided an indication that the missiles were likely protecting a moving armor column, or a high-value target like a field headquarters.

By the mid-1970s, Army and Air Force tactical users were becoming interested in directly accessing the electronic intelligence data collected by the low Earth orbiting satellites, bypassing the NSA. They funded a program called RTIP which in 1977 consisted of two vans—a mobile antenna van and a processing van—that demonstrated the feasibility of direct downlink and on-board processing operation using data from the URSALA III satellite.[12] This was the beginning of what became known as Tactical Exploitation of National CAPabilities, or TENCAP. As more customers began using the data produced by the satellites, they exerted a pull on NRO requirements (see “From the sky to the mud: TENCAP and adapting national reconnaissance systems to tactical operations,” The Space Review, June 19, 2023.)

After RTIP, the NRO’s West Coast office, along with the US Army, developed the Interim Tactical ELINT Processor (ITEP) vans, which were first deployed in 1979. A follow-on van, known as the Tactical ELINT Processor, was planned to work with the FARRAH spacecraft. However, ITEP proved suitable to work with URSALA, RAQUEL, and FARRAH. The Air Force later dropped the “I” from ITEP, referring to it as TEP. The Army renamed its vans as the Electronic Processing and Dissemination System (EPDS), and by 1990 they were widely deployed throughout the world.[13]

According to one person who worked on the satellites during this time, “Back in the early 1970’s the new mission was to get data directly to the commander on the FEBA (Forward Edge of the Battle Area). I had a payload with possibilities if it could be ‘trailerized.’ We decided to go for it but needed a catchy name, so we used DRACULA…Direct Readout and Collection ULA (‘ULA’ was the three-letter shorthand for the URSALA payload).” The Air Force officer put together a briefing for NRO headquarters in the Pentagon. “General Bradburn liked the briefing but trashed the name, saying that he could already hear the welcome by the East Coast: Oh, no, not another blood sucking program from out west!”[14]

Before the launch of URSALA III in 1976, the NRO had decided to let the program die with the end of URSALA IV. However, data users objected and there was pressure to continue or reinstate the program. “In order to do this funding from both the tactical EOB users and the technical intelligence users was needed to cover the costs of a replacement vehicle,” an official history noted.[15] Although details are still limited, apparently this meant that the Army, Navy, and Air Force were required to pay for part of the satellite program. If so, this would have also given the service branches a greater say in the establishment of requirements.

URSALA III and IV, launched in 1976 and 1979, were also designed for general search and electronic order of battle detection missions and had the same frequency range of 2 to 12 gigahertz as their predecessors.[16] But they weighed substantially more, at 259 kilograms (570 pounds), and were designed with 18-month lifetimes. URSALA IV was equipped with an encrypted downlink to enable its use by tactical forces.[17] URSALA III lasted 133 months and URSALA IV lasted 35 months.[18]

The RAQUEL 1A satellite was launched in 1978 and during the 1982 Falklands War it was used to gather signals from Argentine deployed forces that were probably provided to the UK military. The satellite may have played a role in locating the light cruiser ARA General Belgrano, which was sunk by a Royal Navy submarine. (credit: NRO) |

RAQUEL 1 and 1A

RAQUEL was similar to URSALA in design, although intended to search different frequency bands. Whereas URSALA was a “general search” satellite, RAQUEL was described as a “directed search and technical intelligence” satellite. The primary mission of RAQUEL was to “search for, locate, and identify new or unusual signals and to collect emitter mainbeam technical intelligence data on signals in the 4-18 GHz frequency range in accordance with the National SIGINT Requirements List (NSRL). Additional mission requirements include the collection and reporting of operational ELINT data.”[19] The satellite also had a technical intelligence receiver that was capable of recording fine data about the signals it detected. RAQUEL 1 was launched off a HEXAGON satellite in October 1974, and RAQUEL 1A was launched from a HEXAGON in March 1978. RAQUEL 1A cost $13.6 million in 1976, an indication of the approximate cost of the satellites of this type.[20] Initially there had been plans to develop a RAQUEL II, but the cost was deemed excessive.

RAQUEL 1 weighed 256 kilograms (565 pounds) and was described as the “first of new block of increased capability, high reliability spacecraft.” It had a design life of 18 months, but eventually lasted 63 months, until early 1980.[21,22]

RAQUEL 1A was declared operational by mid-May 1978, and “time critical reporting procedures for North Korea, the Middle East, and the Ethiopia-Somalia border were implemented.”[23] It later intercepted and geolocated uplinks from Afghanistan that apparently indicated Soviet plans to invade the country. Shortly after the Soviets began sending aircraft and materials into Afghanistan in 1979, the satellite detected a key Soviet communications satellite uplink.

| More internal volume became available inside the basic subsatellite shape, and designers took advantage of this by packing in even more electronics. One officer who worked on the program calculated that the satellite was now the density of solid mahogany. |

During the 1982 Falklands War, the satellite was reoriented to provide coverage of extreme southern latitudes. This was possible while maintaining much of the usual northern hemisphere coverage. The attitude maneuver was performed during April 24–27, 1982, resulting in two to four passes a day of daytime coverage, providing high-quality collection.[24] Details on the satellite’s value during the Falklands War are unavailable, but obvious targets of interest would have been Argentine air defense radars deployed to the islands, as well as the locations of any Argentine naval vessels. Notably, the Argentine light cruiser ARA General Belgrano was sunk on May 1 by a Royal Navy nuclear submarine, several days after RAQUEL 1A began monitoring the conflict.[25]

The satellites had projected lifetimes of approximately three years but lasted over four times as long. RAQUEL 1A was put into caretaker status in March 1987, but was taken in and out of caretaker status several times after that, including an extended period from August to October 1987 to monitor a still-classified target. In September 1990, operators prepared to take the satellite out of caretaker status again to support Desert Shield/Storm, but this proved unnecessary. RAQUEL 1A re-entered the atmosphere in February 1992, after 14 years in orbit.

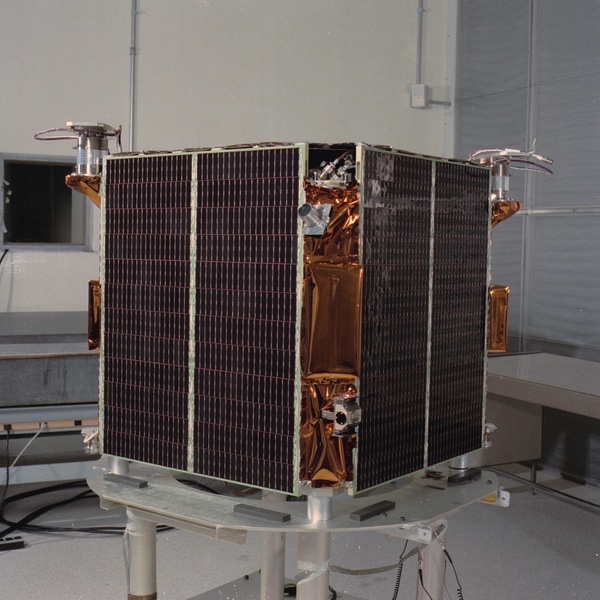

The first two FARRAH satellites were box-like and deployed from HEXAGON satellites. FARRAH III, IV, and V were larger and originally intended for launch from the space shuttle. They were later switched to Titan II rockets. From their low Earth orbit, they could detect radar signals and provide intelligence to tactical forces. (credit: NRO) |

FARRAHs I and II

By 1976, after reversing the decision to end the low Earth orbit signals intelligence program, the NRO decided to recombine the search and electronic order of battle functions (with geolocation) that had been separated into the URSALA satellites and the technical intelligence functions that had been put into the RAQUEL satellites. This single vehicle was initially called “SAT 1.” The SAT 1 study was conducted by Lockheed and combined the functions along with expanded frequency coverage from 2 to 18 gigahertz. The concept was funded in 1977 and construction started in 1978. The satellite was renamed FARRAH.[27]

Changes to the bus-sized HEXAGON photo-reconnaissance satellite enabled even heavier subsatellite payloads to be mounted to their sides.[28] In addition, reduction in electronics size meant that more internal volume became available inside the basic subsatellite shape, and designers took advantage of this by packing in even more electronics. One officer who worked on the program calculated that the satellite was now the density of solid mahogany.

The satellites were equipped with a CDC 469 on-board general purpose digital computer. The computer was used for real time “deinterleaving and readout directly to remote tactical support vans.” This computer was small, lightweight, and energy efficient for its time.[29,30]

FARRAH I and II, launched in 1982 and 1984, respectively, were nearly identical spacecraft whose mission was “to acquire data to satisfy General Search, Operational Elint, and Technical Intelligence requirements on signals in the 2-18 GHz frequency range.” The general search requirements included high priority Soviet, Chinese, and other directed target areas. They also included known interest high-priority targets and strategic and tactical targets associated with weapon systems undergoing development. Operational intelligence was collected for the purposes of indications and warning, and Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty monitoring and force positioning. The FARRAH satellites further developed the capability to provide data to small tactical ground stations for US Army and Air Force units.[31]

The FARRAH satellites were located in orbits of approximately 709 kilometers (383 nautical miles) altitude inclined 96 degrees to the Equator. Each weighed approximately 340 kilograms (750 pounds) and they were designed with 36-month lifetimes, but ended up exceeding this by a substantial amount.[32,33] In early 1991 both satellites lost their final tape recorders, which limited them to transpond collection only, meaning that they could only send signals when they were both in line of sight with an emitter and a ground station. Despite having degraded substantially during the 1980s, both FARRAH I and II operated until the early 2000s, when they were shut down after two decades of service. FARRAH I ceased operations on November 3, 2004, 22 years after launch. FARRAH II was shut down on October 6, 2004, 20 years after launch. Both satellites were placed in a “non-recoverable state” and were projected to remain in orbit in excess of 50 years.

During the 1970s, the P-11-type satellites that had started out as relatively small and inexpensive a decade earlier had steadily grown in mass, cost, and capability. They had also evolved from mostly strategic intelligence collection systems to suppliers of operationally useful intelligence data to tactical units throughout the world. This had involved not only improvements to the satellites, but also new ground systems and new ways of sharing data. That also meant that new users, particularly the United States Army, emerged and began recommending the types of data that was most useful to them. TENCAP started with modest means but continued to grow.

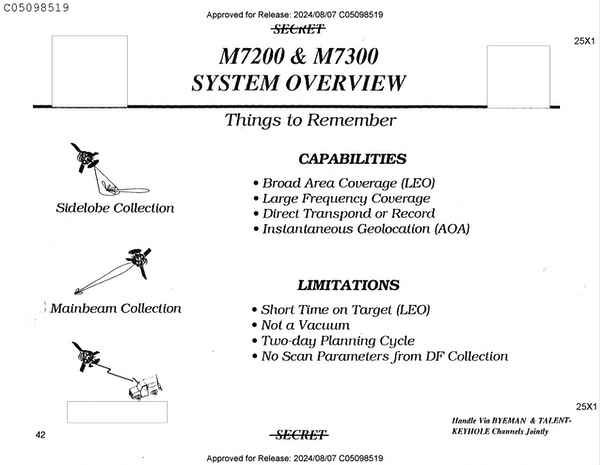

The FARRAH satellites had antennas for intercepting different frequencies. The satellites spun at 50 RPM. (credit: NRO) |

The shuttle era: the FARRAH “tuna cans”

In 1980, the National Reconnaissance Office determined which of its satellite programs would transition to use the Space Shuttle and which would continue to use existing expendable launch vehicles.[36] The GAMBIT and HEXAGON photo-reconnaissance satellite programs were both scheduled to retire during the 1980s and thus would not be modified to fly on the shuttle. Because the smaller Program 989 satellites like URSALA, RAQUEL, and FARRAH had launched off the side of HEXAGON satellites, they would need a new way to reach orbit after the end of the HEXAGON program.

| More internal volume became available inside the basic subsatellite shape, and designers took advantage of this by packing in even more electronics. One officer who worked on the program calculated that the satellite was now the density of solid mahogany. |

As a result of this decision, the NRO performed an “ELINT Mix Study” and related studies to examine issues related to the transition of low altitude SIGINT programs to the shuttle. One possibility was combining existing low-altitude programs, or to replace selected low-altitude capabilities with an upgraded high-altitude satellite (as had been done with the large Program 770 STRAWMAN satellites in the early 1970s). The NRO determined that existing systems should be upgraded but not combined. The upgraded satellites would also be launched along with Improved PARCAE ocean surveillance satellites on the shuttle.[37]

NRO officials decided not only that future FARRAH satellites could be launched by the shuttle, but that they could be substantially enlarged to take advantage of the shuttle’s greater lift capabilities. At least three of the new satellites would be procured: FARRAH III, IV, and V. They would be larger and heavier than their predecessors with the same name, equipped with more antennas and receivers. The new satellites would weigh more than 1,360 kilograms (3,000 pounds), compared to 340 kilograms for FARRAHs I and II.[38]

According to an official history updated in 1991, the switch from expendable rockets to the shuttle and then back again for both the FARRAH and PARCAE programs “proved extremely costly” for both programs. |

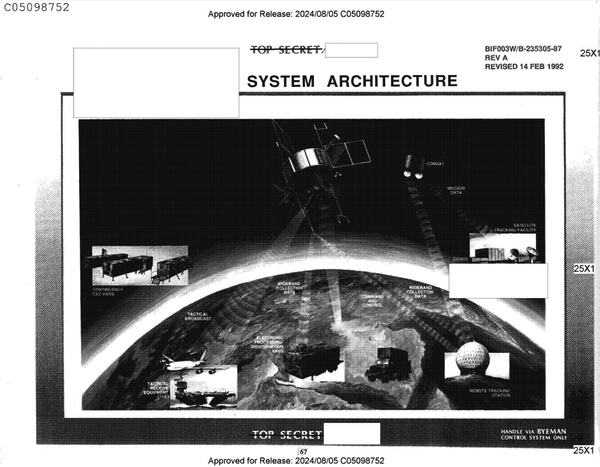

The NRO has now released illustrations of the FARRAH III satellite, indicating that it was a large, squat cylinder, generally referred to as a “tuna can,” and equipped with three dish antennas and several other pole antennas like its much smaller predecessor. FARRAH III had a tactical on-board processor and could direct downlink its data to users. One artist illustration showed this data being transmitted to fixed ground stations, ground-based mobile vans, and an aircraft carrier. FARRAH could therefore send data directly to some ships. In contrast, at the time, data was apparently not directly downlinked from the PARCAE ocean-surveillance satellites to ships but was first relayed through fixed ground stations for processing and then through geosynchronous communications satellites to ships at sea, as well as through a dedicated communications satellite network in highly elliptical orbits.

The satellites spun at 50 rpm and had three high-gain parabolic antennas that covered 0.8 to 6, 6 to 12, and 12 to 18 gigahertz. The latter used “cooled front-end electronics” to receive the higher frequencies. They were also equipped with single and double-boom omni antennas to suppress sidelobe interceptions.[39] FARRAH V had additional capabilities that remain classified.[40] FARRAH III was apparently designed with a three-year nominal lifetime.[41]

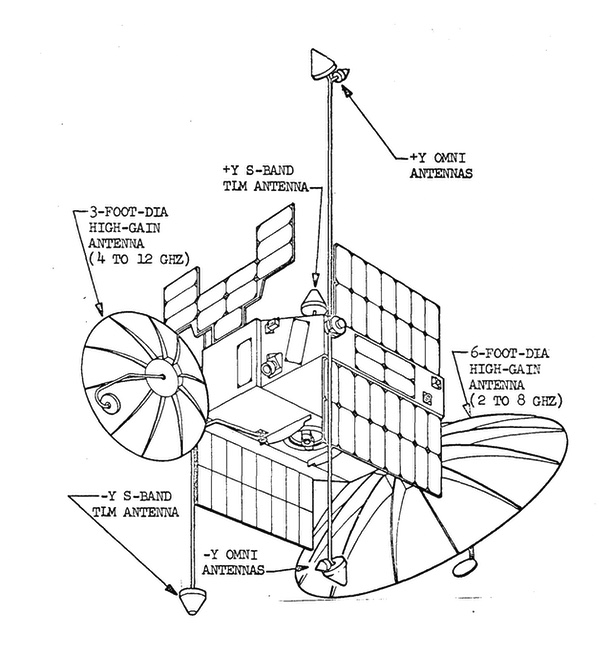

In the mid-1980s, several of the FARRAH signals intelligence satellites intended for shuttle launch were switched to use converted Titan II ICBMs. Three were launched starting in 1988, although FARRAH IV failed in orbit. (credit: Peter Hunter) |

Although the plan had been to launch at least the first three of these larger FARRAH satellites on the shuttle, the NRO official in charge of the FARRAH program realized that this would require major upgrades to the shuttle that might not be funded in time, if at all, and he chose to remove the satellites from the shuttle and launch them on converted Titan II ICBMs instead. Eventually, the PARCAE program also switched from the shuttle to the expensive Titan IV rocket. According to an official history updated in 1991, the switch from expendable rockets to the shuttle and then back again for both the FARRAH and PARCAE programs “proved extremely costly” for both programs.[42]

FARRAH III was launched in September 1988. FARRAH IV was launched in September 1989 but failed soon after reaching orbit.[43] FARRAH V was launched in September 1992. No details have been released about when FARRAH III and V ceased operating, but in 2021 they were observed still spinning in orbit, and they could possibly still be operational. In 1993, three additional Titan II rockets that had been assigned to “classified payloads” were made available for other programs. It is likely that these three were originally allocated to FARRAHs VI-VIII, but a program reorientation resulted in their cancellation.[44]

Although designed with a three-year nominal lifetime, FARRAH III was apparently still alive nine years later.[45] Considering that its smaller predecessors lasted two decades, FARRAHs III and V could have even been operational into the 2010s. Recently, the Space Force celebrated the 30th anniversary of operations of the first Milstar communications satellite, and Defense Support Program missile warning satellites remain operational after two decades in orbit, indicating that long lifetimes in orbit are not unusual for military satellites.

The FARRAH satellites could supply intelligence data to tactical forces, ships, and even aircraft. Data could be recorded for later transmission, or directly transponded to a ground station as soon as it was received. Fixed ground stations could also re-transmit data. (credit: NRO) |

The data from the FARRAH satellites could be sent down in several different ways. Data from the Tactical Onboard Processor could be transmitted by direct downlink to receivers, either fixed or mobile, including ships at sea. The signals intercepted by the satellites could be either recorded for later playback, or “transponded,” meaning that the data was sent as soon as it was collected. Data sent to a fixed ground station could then be relayed through a military comsat to another ground station or other users.[46]

An NRO document explained that the remote operating locations “are NRO assets strategically located near high interest areas, providing greater, near realtime coverage without putting tape recorder cycles on the satellites. This contiguous field of view between target area and receive site reduces the number of tape recorder cycles on the vehicles while preserving the intelligence value. The mechanical tape recorders are the life-limiting factor on our store-and-forward mission capabilities.” There were three remote operating locations for the satellites, although their locations are still classified.[47] The Mission 7300 data was also “fused” with other data, most likely from the PARCAE ocean surveillance satellites.

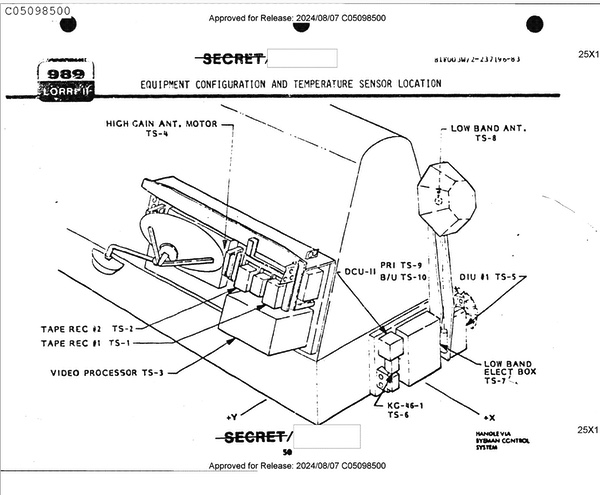

The LORRI 2 payload was attached to the last HEXAGON photo-reconnaissance satellite and was designed to search a little-used portion of the frequency spectrum to determine if it was being used by foreign military powers. The payload was destroyed when the Titan rocket carrying it blew up soon after launch. (credit: NRO) |

LORRI I and II

In addition to the FARRAH satellites that served general electronic intelligence collection requirements, SAFSP also oversaw the development of several specialized systems during this period, such as LORRIs I and II, which were intended to survey portions of the spectrum that were still mostly unused by the military.

The concept for LORRI I was developed in 1973–1974, but limited funding delayed its development.[48] LORRI I was an attached payload carried on a HEXAGON satellite launched in 1980 and was “the first satellite collector of SIGINT in the 26-to-42-gigahertz frequency range. It remained with its host spacecraft for its entire lifetime of eight months.[49] LORRI I was intended to survey this frequency range to determine if it was being used by the Soviet Union or other countries for new purposes. It apparently demonstrated that the frequency range was mostly quiet. According to one document, the Naval Research Laboratory’s NRO component office (known as Program C) “flew an earlier, largely unproductive mission” similar to LORRI I. (It is unclear what this mission was, but it may have been included on a POPPY satellite.)[50]

LORRI II was expanded to cover three additional frequency ranges. These were 92 to 96 gigahertz, 70 to 74 gigahertz, and a VHF collection window centered at 158 megahertz to collect signals from a still-classified radar target as well as the large Soviet HEN HOUSE ABM and space-tracking radars.[51]

LORRI II was mounted to the side of the last HEXAGON photo-reconnaissance satellite, which was planned to have a much longer lifetime than previous HEXAGONs, staying in orbit long after its film ran out. That satellite and the LORRI II payload were lost when the Titan 34D rocket exploded soon after liftoff in April 1986. This prompted the NRO to search for near-term alternatives to replace the capability. One solution was a small satellite known as GLORIA I. The other was to make modifications to FARRAH III, then approximately one year from launch.[52]

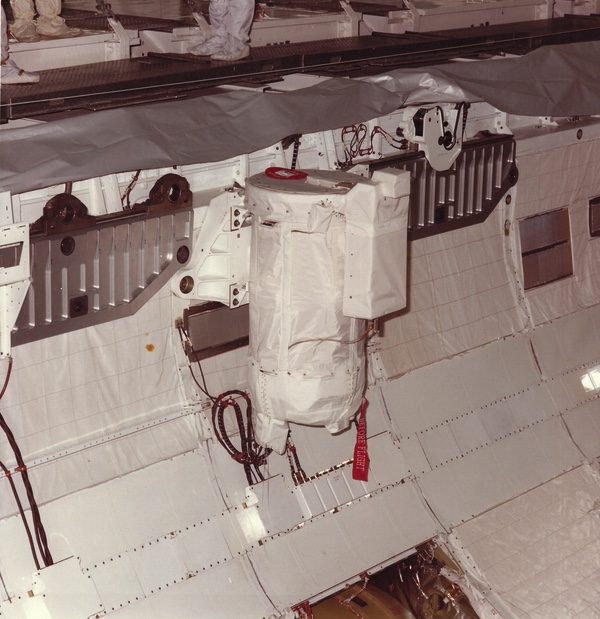

Two classified GLORIA satellites were carried into orbit on space shuttle missions STS-28R in 1989 and STS-39 in 1991. The secret satellites were carried in containers in the shuttle's payload bay. (credit: NASA) |

GLORIA

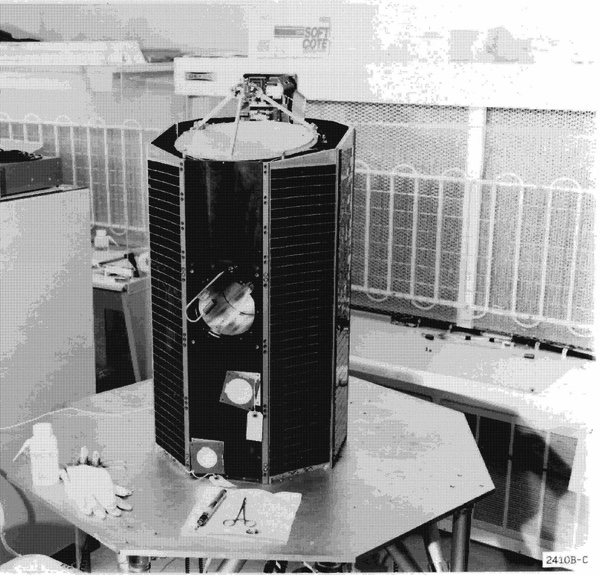

GLORIA I was a small satellite deployed from the payload bay of the space shuttle Columbia during the STS-28R mission in 1989. It was a spin-stabilized satellite with a single one-foot (30-centimeter) parabolic receiver. GLORIA I was originally conceived to collect signals in the 18-to-26-gigahertz region, but the loss of LORRI II resulted in a change to intercept a higher frequency band.[53] GLORIA I’s primary mission was a general search for pulsed emitters in the 30-to-38-giaghertz frequency region, repeating a survey of this frequency band that had been conducted by LORRI I nearly a decade earlier. It was also intended to test the feasibility of low-cost, quick reaction satellites and was generally considered a success. Because GLORIA did not find any new or unusual uses for this frequency region, the NRO determined that another survey would not be needed for a decade. Early during the mission, the satellite’s solid state memory suffered from radiation and “latch up” problems, which were overcome.

The GLORIA satellites were relatively small (note the scissors on the table) and used to search portions of the radio spectrum for new emitters. (credit: NRO) |

GLORIA II was a nearly identical satellite deployed from the space shuttle Discovery during the STS-39 mission in 1991. GLORIA II’s memory, command decoder, and mass memory controller had been upgraded to overcome early flight deficiencies.[54] Both GLORIA satellites were built by Ball Brothers, with the payload built by E-Systems. They were intended to meet a requirement for quick response, low cost, and limited time mission objectives. GLORIA II surveyed 18-to-26-gighertz frequencies for radar and communications emitters, a frequency region that had not previously been covered by NRO satellites. GLORIA II did detect an unknown radar, although details are unavailable. A GLORIA III was apparently evaluated, but not developed.

CARRIE was launched in 1994 as part of the STEX satellite (also known as DARPASAT). It was designed to detect communications and provide intelligence data to American tactical forces. (credit: NRO) |

CARRIE

CARRIE stood for COMINT and Rapid Reporting Interferometry Experiment.[56] CARRIE started out as a concept within the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) for an “experimental satellite providing direct support to warfighters.” The planned mission lifetime was one year, but the satellite lasted eight years until reentering the atmosphere in 2002. The satellite was designed to be quickly responsive, meaning that the collection requirements could be rapidly changed while the satellite was overhead.

The CARRIE satellite was launched as a ride-share on a Taurus rocket in 1994, part of the STEX satellite. One of its contributions to intelligence collection was finding evidence of “heritage” Soviet communications systems still operating in Cuba. It also geolocated new and unidentified emitters in multiple countries.

CARRIE was considered to be part of Mission 7200, because it was attached to STEX. CARRIE’s focus was on communications intelligence. STEX was apparently also used to relay data from FARRAH satellites that had lost their tape recorders a few years earlier, although it is unclear how STEX accomplished this.[57]

Mission 7300 ends

A summary produced in late 1997 indicated that Mission 7300 (the FARRAH satellites) and Mission 7200 (the CARRIE satellite) had detected 55 new signals in 1993, 52 in 1994, 49 in 1995, 33 in 1996, and 18 new signals by September 1997.[58] Clearly the number of new detections was declining over this period, although whether this was because of the collapse of the Soviet Union or the limitations of the satellites is unknown.

As early as 1980 there were studies within the NRO about possibly merging the PARCAE ocean surveillance system with the satellites of Mission 7300. That merger was rejected at the time in favor of upgrading both systems. But the existence of two systems for low Earth orbit signals intelligence collection, along with the increasing cost of both, required NRO officials to defend them, apparently both from the White House’s Office of Management and Budget and relevant congressional committees.

| The Mission 7100 ocean surveillance program ended in 2008, but it is unclear when, or if, the Mission 7300 signals intelligence program also ended, or if some of the satellites remain in operation despite having been supplanted by a new effort starting in the 1990s. |

At some point during the 1980s, the program office for Mission 7300 produced a document explaining “Why Mission 7300 does so well in detecting new signals.” It declared that the system was “superior in its ability to find new signals in the SIGINT environment because it has the following inherent characteristics: special system capabilities, and extensive parametric and geolocation information from a single blip (pulse or CW sample).”[59] The special system capabilities included full Earth coverage, including the southern hemisphere and broad ocean areas. It “continues to evaluate the world environment prior to, during, and after events. While other systems are focusing on world events, Mission 7300 continues to provide General Search data.” It also had extensive frequency coverage of 2 to 18 gigahertz, plus 20 to 60 megahertz, 150 to 170 megahertz, and 30 to 38 gigahertz, with future capability (possibly in FARRAH V) including the regions 0.8 to 2 gigahertz and 18 to 26 gigahertz. The system had rapid frequency span coverage and geolocation with a single collector.

All of the Mission 7300 data was processed and analyzed. This was apparently in contrast to the PARCAE data, which was not completely processed. As one former PARCAE contractor noted, at least in the early years of the program much of the data was discarded because there was too much to process.

According to documents released by the NRO, the low Earth orbit signals intelligence mission and the ocean surveillance mission were eventually merged during the 1990s. The Mission 7100 ocean surveillance program ended in 2008, but it is unclear when, or if, the Mission 7300 signals intelligence program also ended, or if some of the satellites remain in operation despite having been supplanted by a new effort starting in the 1990s.

Today, satellite intelligence is integrated into military operations more extensively than ever before, the ultimate legacy of Program 989 and its satellites named after movie actresses.

References

- “P-989 Historical Summary and Aerospace Support,” November 1972, C05098605, p. 3. This and the other documents are available here.

- The Program 989 designation was discontinued sometime in the 1980s, possibly replaced by another name which is deleted in the titles of several late-1980s documents. The deletions are too long to be a number. For example, see: “[Deleted] SIGINT Collection Systems,” November 1, 1987, C05098752.

- Mission 7800 referred to an “intrusion detection system” probably mounted to most satellites to detect attempts to hack them. This was the successor to a program in the 1960s known as “BIT.”

- “Mission 7300 Evolution,” [n.d. but probably 1990], C05098529, p. 19.

- Ibid. Information on MABELI is on pp. 15-19.

- Ibid., p. 22. According to one document, several of these are acronyms, although it is highly likely that they were “backronyms,” meaning that they came up with the name first and then created an acronym that fit. They are: URSALA = Universal Radar Search And Location Acquisition; RAQUEL = Radar AcQUisition Equipment with Location; SHARON = Signal Handling And RecognitiON. “P-989 Historical Summary and Aerospace Support,” November 1972, C05098605.

- Ibid., p. 20.

- Ibid., p. 22.

- “A Brief History of the U.S. Low Earth Orbit Reconnaissance Programs,” n.d. C05027386. (Note that another version of this history is dated 1991.)

- “Mission 7300 Evolution,” p. 6.

- “A Brief History of the U.S. Low Earth Orbit Reconnaissance Programs,” n.d. C05027386.

- “Mission 7300 Evolution,” pp. 25-26.

- Ibid.

- Peter Swan and Cathy Swan, "Birth of Air Force Satellite Reconnaissance," Lulu.com, 2015, p. 129.

- “Mission 7300 Evolution,” p. 31.

- “Subsatellites,” n.d. (1974) C05098790.

- “A Brief History of the U.S. Low Earth Orbit Reconnaissance Programs,” n.d. C05027386.

- “Mission 7300 Evolution,” p. 6.

- “Mission 7300 Monthly Collection Summary,” September 1988, C05098530.

- “989 Program Plan,” July 7, 1976, C05098571.

- “Subsatellites.”

- “Mission 7300 Evolution,” p. 6. Although some documents use Roman numerals for the two RAQUEL satellites (I and IA), others use the numbers 1 and 1A.

- “Section VI: Spacecraft,” n.d. (but approximately February 1992), C05098535.

- Ibid.

- “Mission 7300 Evolution.” Falkland Islands War is mentioned on p. 32.

- “Section VI: Spacecraft.”

- “Mission 7300 Evolution,” p. 31.

- “A Brief History of the U.S. Low Earth Orbit Reconnaissance Programs,” n.d. C05027386.

- “[Deleted] SIGINT Collection Systems,” November 1, 1987, C05098752.

- “Mission 7300 Program History,” n.d., C05098534.

- “Mission 7300 Monthly Collection Summary,” September 1988, C05098530

- “A Brief History of the U.S. Low Earth Orbit Reconnaissance Programs,” n.d. C05027386. Another source indicates that the design lifetime was 2.5 years, or 30 months.

- “Mission 7300 Program History.”

- Peter B. Teets, Director, NRO, “Termination of FARRAH-1 (Mission 7346) Mission Operations,” November 12, 2004. C05098412.

- Peter B. Teets, Director, NRO, “Termination of FARRAH-2 (Mission 7347) Mission Operations,” October 14, 2004. C05098413.

- “A Brief History of the U.S. Low Earth Orbit Reconnaissance Programs,” n.d. C05027386.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Mission 7300 Payload,” n.d., C05098533, pp. 8-9.

- “[Deleted] Orientation Course,” M7200 & M7300 System Overview, April 28, 1998, C05098519, p.11.

- Ibid,, p. 13. The document is somewhat confusing because although the cover page indicates it was produced in 1998, page 13 includes a reference to the FARRAH program being “Still alive in 2005!”

- “A Brief History of the LEO Program,” (file dated 8/13/91), C05098892, pp. 7-8.

- FARRAH IV is referenced in C05098529, p. 3.

- See Jeffrey Richelson, The U.S. Intelligence Community, 4th Ed. 1999, pp. 195-186.

- “[Deleted] Orientation Course,” p. 13.

- “Mission Planning Mission 7300,” contained in “Chapter 5, Command and Control,” [n.d. but probably 1990], p. 41. C05098521.

- Ibid.

- “Mission 7300 Evolution,” p. 49.

- “Program History Mission 7300,” n.d. (approx. 1985), C05098521.

- “Mission 7300 Evolution,” p. 49.

- Ibid.

- William H. Webster, Director of Central Intelligence, to Louis Stokes, Chairman, Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, U.S. House of Representatives, July 24, 1987. CO5098518. The letter notes that the small payload would be available for launch in summer 1988, but it was not launched until summer 1989.

- “Mission 7300 Evolution,” p. 49.

- Ibid., p. 50.

- Section II, “The [Deleted] Low Earth Orbit SIGINT System (Mission 73XX), November 3, 1989, C05098800

- “Mission 7300 Program History,” n.d., C05098534.

- “[Deleted] Orientation Course,” p.12.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- “Why Mission 7300 Does So Well in Detecting New Signals,” [n.d.], C05098523.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.