A final twist in the Starliner sagaby Jeff Foust

|

| “Things that I can’t control I’m not going to fret over,” Wilmore said in a call with reported a week after Starliner returned. “My transition maybe wasn’t instantaneous but it was pretty close.” |

Freedom’s splashdown marked the end of the Crew-9 mission, bringing back NASA astronaut Nick Hague and Roscosmos cosmonaut Aleksandr Gorbunov, who launched to the ISS on that spacecraft in late September. But the bulk of the attention about the spacecraft’s return focused on its other two occupants, NASA astronauts Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore, who had been on the station since June when they arrived on Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner on the Crew Flight Test (CFT) mission.

Williams and Wilmore, of course, were only scheduled to spend a short time on the station, as little as eight days. But days turned to weeks and then months because of problems with Starliner that eventually led NASA to bring back Starliner without a crew on board in September (see “Whither Starliner?”, The Space Review, September 9, 2024). NASA removed two astronauts originally assigned to Crew-9 to free up seats that Williams and Wilmore would use to return home.

The splashdown returned Williams and Wilmore back to Earth more than nine months after their launch, ending that extended mission. But it was one that took unexpected political twists in the final months that overshadowed the issues with the spacecraft that took the two to the station.

Neither stranded nor abandoned

Immediately after Starliner’s uncrewed departure, the two CFT astronauts said they were taking the extended mission in stride. “Things that I can’t control I’m not going to fret over,” Wilmore said in a call with reported a week after Starliner returned. “My transition maybe wasn’t instantaneous but it was pretty close.”

In the months that followed, the two were full members of the ISS crew, doing research and maintenance. The only controversy was tabloid media fodder that Williams was somehow unwell, based on photos her on the station; she stated she was healthy.

That changed, though, shortly after Donald Trump was inaugurated as president. SpaceX CEO Elon Musk, also a close advisor to the president, posted on social media January 28 that the president asked SpaceX to bring the two “stranded” astronauts on the station—meaning Williams and Wilmore—back home “as soon as possible.”

Trump, in his own post hours later, confirmed that. “I have just asked Elon Musk and @SpaceX to ‘go get’ the 2 brave astronauts who have been virtually abandoned in space by the Biden Administration,” he stated. “Elon will soon be on his way. Hopefully, all will be safe. Good luck Elon!!!”

It was unclear at the time what it meant for SpaceX to bring the two back as soon as possible: an early return of Crew-9, a dedicated mission of some kind?

| “They didn’t have the go-ahead with Biden,” Trump said. “He was going to leave them in space. I think he was going to leave them in space… He didn’t want the publicity.” |

It was only the next day before NASA provided any guidance: “NASA and SpaceX are expeditiously working to safely return the agency’s SpaceX Crew-9 astronauts Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore as soon as practical, while also preparing for the launch of Crew-10 to complete a handover between expeditions,” the agency stated. That was, of course, the original plan that NASA announced last August.

The controversy continued as Musk and Trump both claimed that the CFT astronauts were “abandoned” on the station for political reasons. “They were left up there for political reasons, which is not good,” Musk said in a joint appearance with Trump February 18 on Fox News.

“They didn’t have the go-ahead with Biden,” Trump said. “He was going to leave them in space. I think he was going to leave them in space… He didn’t want the publicity.”

Musk also claimed to have offered the Biden Administration a proposal to bring back Williams and Wilmore early. “SpaceX could have brought them back several months ago,” he said in one social media post. “I OFFERED THIS DIRECTLY to the Biden administration and they refused.” (The post was in response to criticism from ESA astronaut Andreas Mogensen; Musk’s response included a slur directed at Mogensen.)

Musk has repeated the claim that he offered the Biden Administration a plan for an earlier return of the two astronauts, but has not provided any details such as who he contacted at the White House and when, as well as what the plan was itself. Also unclear was why Musk would directly go to the White House, given his poor relationship with the Biden Administration at the time, rather than contact NASA. Former agency leaders, such as administrator Bill Nelson and deputy administrator Pam Melroy, said they were unaware of any proposals Musk might have made to the White House.

Any sort of early return of Williams and Wilmore would have been difficult to pull off. SpaceX had four operational Crew Dragon spacecraft, including Freedom at the ISS and Endeavour, which returned from the ISS in late October for the Crew-8 mission. Resilience was flown on the Polaris Dawn private astronaut mission in September (and will launch again next week on Fram2, another private astronaut mission); it also lacked a docking adapter needed for ISS missions. That left only Endurance, which was being prepared for the Ax-4 private astronaut mission to the ISS in the spring.

SpaceX was also building a fifth Crew Dragon capsule, which was slated to fly for the first time on Crew-10. But in December, NASA said that delays in the production of that spacecraft would delay the Crew-10 launch, then scheduled for mid-February, to late March. SpaceX was thus helping extend the stay of the “abandoned” astronauts.

With the prospect of more delays in that new Crew Dragon, NASA announced in mid-February that it would instead use Endurance. That would allow Crew-10’s launch to be moved up a couple weeks, although still behind its earlier schedule. Ax-4 will instead use the new, unnamed Crew Dragon, likely in May or June.

While this was going on, the CFT astronauts were pushing back against the narrative that they were “stranded” or “abandoned” on the station. “I don’t think I’m abandoned. I don’t think we’re stuck up here,” Williams said in one interview with CBS in early February. “We’ve got food. We’ve got clothes. We have a ride home in case anything really bad does happen to the International Space Station.”

“We don’t feel abandoned,” Wilmore said in another interview with CNN a few days later. “We don’t feel stranded. I understand why others may think that. We come prepared. We come committed.”

| “Steve had been talking about how we might need to juggle the flights and switch capsules, you know, a good month before there was any discussion outside of NASA, but the President’s interest sure added energy to the conversation,” said Bowersox. |

In a press conference from the station in early March, Wilmore appeared to endorse Musk’s claim that he offered an early return of the astronauts. “I can only say Mr. Musk, what he says, is absolutely factual,” Wilmore said, but added he did not have any knowledge himself of any proposals. “We have no information about that whatsoever, though: what was offered, what was not offered, who it was offered to, how that process went. That’s information that we simply don’t have.”

At two briefings in March, one a week before the March 14 launch of Crew-10 and the other hours after the Crew-9 splashdown, NASA officials danced around questions about Musk’s comments and any proposals he may or may not have made to bring Williams and Wilmore home earlier.

Steve Stich, NASA commercial crew program manager, said before the Crew-10 launch that planning to swap Crew Dragon spacecraft predated the January comments by Musk and Trump. The goal was to get Crew-10 launched, and Crew-9 returned, before a Soyuz crew rotation flight in April, followed by a cargo Dragon mission.

“I can verify that Steve had been talking about how we might need to juggle the flights and switch capsules, you know, a good month before there was any discussion outside of NASA, but the President’s interest sure added energy to the conversation,” added Ken Bowersox, NASA associate administrator for space operations.

He said NASA had worked with SpaceX last year on alternative options for bringing back Wilmore and Williams. “When it comes to adding on missions or bringing a capsule home early, those were always options, but we ruled them out pretty quickly, just based on how much money we've got in our budget and the importance of keeping crews on the International Space Station.”

Bill Gerstenmaier, a former NASA official who is now vice president of build and flight reliability at SpaceX, agreed, offering no details on what SpaceX might have proposed for an earlier return. “We worked with NASA collectively to come up with the idea of just flying two crew up on Crew-9, having the seats available for Suni and Butch to come home, and that's what NASA wanted, and that fit their plans,” he said.

NASA officials were no more forthcoming after Crew-9’s splashdown. “That excited the system. It gave us some energy in the system,” Joel Montalbano, deputy associate administrator for NASA’s Space Operations Mission Directorate, said of the Trump administration’s role in the mission’s return.

That came after a social media post by Trump on March 17 where he said he had talked with NASA’s acting administrator, Janet Petro. “Janet was great. She said, ‘Let’s bring them home NOW, Sir!’ — And I thanked her,” he wrote. (A NASA spokesperson confirmed that Trump and Petro had talked, but did not provide any details of that conversation, including whether she uttered the quote Trump attributed to her.)

“Per President Trump’s direction, NASA and SpaceX worked diligently to pull the schedule a month earlier,” Petro said in a NASA press release after splashdown. “This international crew and our teams on the ground embraced the Trump Administration’s challenge of an updated, and somewhat unique, mission plan, to bring our crew home.”

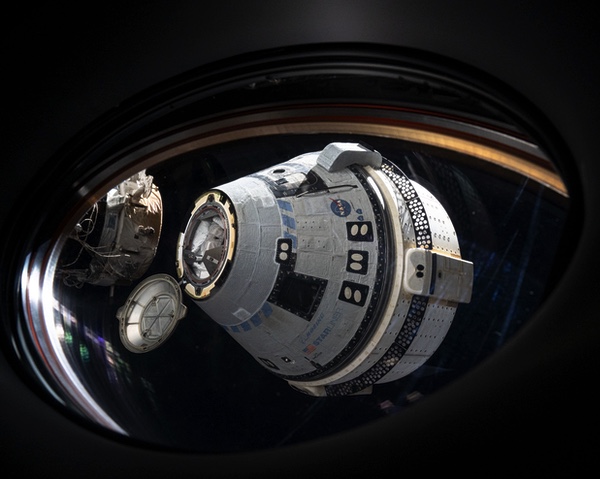

The CST-100 Starliner spacecraft departing from the ISS in September, as seen from a window on a Crew Dragon spacecraft also at the station. There is no firm schedule yet for Starliner’s return to the ISS. (credit: NASA) |

Starliner’s future

The discussion about how the two Starliner astronauts would be brought back to the station overshadowed another issue: why they had to stay on the ISS in the first place. Neither NASA nor Boeing had said much about the issues with Starliner in the months since the spacecraft’s uncrewed return in early September.

NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel (ASAP), in its annual report released in February, praised NASA for its decision to return Starliner uncrewed, citing the failure of a thruster—unrelated to those that caused problems during docking—on the capsule’s return. “Had the crew been aboard, this would have significantly increased the risk during reentry, confirming the wisdom of the decision,” the report stated.

Paul Hill, a member of ASAP, said at a late January meeting of the committee that there was progress in the post-flight investigation. “NASA reported that significant progress is being made regarding Starliner CFT’s post-flight activities,” he said. “Integrated NASA-Boeing teams have begun closing out flight observations and in-flight anomalies.”

However, that excluded the propulsion system, whose helium leaks and thruster problems were key reasons why NASA decided not to have Williams and Wilmore return on the spacecraft. “The program anticipates the propulsive system anomalies will remain open,” he said, “pending ongoing test campaigns.”

| “The next flight up would really test all the changes we’re making to the vehicle,” Stich said of Starliner, “and then the next fight beyond that, we really need to get Boeing into a crew rotation.” |

It wasn’t until the two briefings this month that NASA officials provided details into the status of Starliner and when—and how—it will next fly. “We're making good progress on closing out the inflight anomalies and the inflight observations” from the CFT mission, Stich said before the Crew-10 launch, noting that about 70% of those issues were now closed.

But, he said more testing was needed of Starliner’s propulsion system, such as new seals to correct the helium leaks and tests of the thermal environment of the “doghouses” on Starliner’s service module that host thrusters. “Once we get through those campaigns, we’ll know a little bit better” when to schedule the next Starliner flight, he said.

After Crew-9’s return, Stich said NASA wanted to fly another Starliner test flight, then have it start flying the same crew rotation missions that Crew Dragon has been doing since 2020. “So, the next flight up would really test all the changes we’re making to the vehicle, and then the next fight beyond that, we really need to get Boeing into a crew rotation. So, that’s the strategy.”

That test flight, he added, could be with or without a crew, but even if it is an uncrewed flight it would be the same configuration as a crewed vehicle.

One key issue beyond Starliner’s technical problems is Boeing’s continued willingness to support the program. The company reported more than half a billon dollars in charges against earnings due to Starliner in 2024, and overall losses now exceed $2 billion. At the same time, Kelly Ortberg, who became Boeing CEO last year, said he wanted to find non-core programs outside of commercial aviation and defense to cut to help the company get back on its financial feet.

Stich said after splashdown that Boeing remained committed to Starliner. “Boeing, all the way up to their new CEO, Kelly [Ortberg], has been committed to Starliner,” he said, citing its ongoing work to resolve the problems Starliner suffered on the CFT mission. “I see a commitment from Boeing to continue the program. They realized that that they have an important vehicle, and we were very close to having the capability that we would like to field.”

One issue is finding a place in the schedule for both another Starliner test flight and beginning crew rotation missions. A busy schedule of visiting vehicles to the ISS, including cargo Dragon missions and the Ax-4 private astronaut mission, means the next opportunity for Starliner to go to the ISS might not be until late this year or early next year, assuming the spacecraft is ready.

NASA is still working on the schedule for future commercial crew missions. Crew-11 will launch as soon as late July on another Crew Dragon. Stich said NASA has not decided if it will be followed early next year by either Crew-12 or the first operational Starliner mission, Starliner-1. “We probably have a little bit more time, as we get into the summer and understand that the testing we’re going to go do to make that decision,” he said. The Starliner astronauts know all about having some extra time.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.