Flashlights in the darkby Dwayne A. Day

|

| This declassification has been in the works for a long time. It was originally proposed for the late 1990s and then postponed. It is now timed to coincide with the NRO’s fiftieth anniversary. |

According to several sources, the NRO plans to display several declassified objects on the grounds of the Smithsonian’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Museum for a short period of time, possibly only on September 17. One of these objects is the massive camera system from the KH-9 HEXAGON. Another is the camera system from the KH-7 GAMBIT. Several other objects may be displayed as well. After a very brief appearance at the museum, the objects are going to be hauled away for display at the US Air Force Museum in Dayton. It is not clear if they will return to the Udvar-Hazy Museum, which is busy preparing for the exchange of the Enterprise with the space shuttle Discovery next year. Although the Air Force played a vital role in these programs, the Dayton museum is not as easy to reach as the Udvar-Hazy Museum, which is also located only a few kilometers from the NRO’s headquarters.

This declassification has been in the works for a long time. It was originally proposed for the late 1990s and then postponed. It is now timed to coincide with the NRO’s fiftieth anniversary, and a massive party will take place at the museum next Saturday evening. The National Reconnaissance Office was created in 1961, but its existence was not officially acknowledged by the U.S. government until 1992. Gradually the agency that develops, purchases, and operates the United States’ intelligence satellites has revealed more aspects of its operations, usually in fits and starts. After several years of relative openness in the late 1990s, the NRO, like many government intelligence agencies, became much less open during the Bush Administration and after September 11, 2001. The HEXAGON and GAMBIT declassifications will be the biggest release of information from the NRO since the mid-1990s, when an executive order signed by President Clinton—apparently over some opposition from NRO leadership—declassified the CORONA reconnaissance satellite program. Over the next several years there will probably be tens of thousands of pages of documents on these programs declassified and released to the public.

The NRO, unlike the rest of the American civilian and military space programs, has been on a roll lately. Typically the NRO launches a couple of classified intelligence satellites a year. But the NRO launched six intelligence satellites in seven months earlier this year. According to Alden Munson, the former US deputy director of national intelligence for acquisition and technology, these included a satellite that was “a culmination of herculean efforts to overcome a painful program initiation” and another that represented “a critical effort to recover capabilities compromised by an earlier program failure and cancellation.” At a time when the US government is not held in terribly high regard by its citizens, and when NASA has succumbed to a great deal of political squabbling, the NRO can justifiably stand up and take a bow—something that its officials generally don’t like to do.

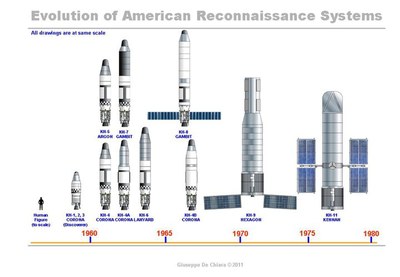

The basic outlines of the HEXAGON and GAMBIT programs have emerged over the past few years. HEXAGON was a search system created to image vast swaths of the Soviet Union to provide indications of changes on the ground, and also provide enough clarity to determine what those changes were. GAMBIT started out as a replacement for the U-2 spyplane, intended to reveal whether or not Soviet ICBMs were standing on their launch pads. It later evolved into a system with extremely high resolution, eventually reaching the point where it reportedly could image an object as small as a baseball from orbit. This high resolution was intended to provide technical details about its targets, such as highly accurate measurements of the length and diameter of Soviet ICBMs, thereby providing information on the amount of fuel they contained—useful for determining their performance characteristics such as range and payload.

Over the past several years I have written a number of articles about GAMBIT and HEXAGON. See, for instance:

- “The invisible Big Bird: why there is no KH-9 spy satellite in the Smithsonian”, The Space Review, November 8, 2004;

- “A paler shade of black”, The Space Review, September 20, 2010;

- “The flight of the Big Bird (part 1)”, The Space Review, January 17, 2011;

- “The flight of the Big Bird (part 2)”, The Space Review, February 7, 2011;

- “The flight of the Big Bird (part 3)”, The Space Review, February 21, 2011;

- “The flight of the Big Bird (part 4)”, The Space Review, March 28, 2011;

- “Ike’s gambit: The development and operation of the KH-7 and KH-8 spy satellites”, The Space Review, January 5, 2009.

- “Ike’s gambit: the KH-8 reconnaissance satellite”, The Space Review, January 12, 2009;

- “Black fire: de-orbiting spysats during the Cold War”, The Space Review, October 25, 2010.

These articles were based upon woefully incomplete information. They certainly contain inaccuracies, and they will probably—hopefully—be completely out of date in only a few days. When the programs are declassified, you can bet that I’ll be gathering as much information as possible.

The NRO released a few details last month about a recent launch, NROL-66, that carried a satellite called Rapid Pathfinder. (credit: NRO) |

This declassification event is likely to be the last major one from the NRO for the next several decades. The general policy seems to be that the government will not declassify intelligence satellite programs until at least 25 years after the last spacecraft has ceased operation. Considering that some satellites can remain in production for several decades, and at least some satellites reportedly have continued operating for up to twenty years, it is obvious that some of the projects started in the 1960s and later will remain classified for a half-century or more after they are started, if not longer.

| This declassification event is likely to be the last major one from the NRO for the next several decades. |

That does not mean that the NRO will remain completely secretive. Sometimes the office lets out little bits of information without fanfare. In August, NRO Director Bruce Carlson gave a talk about small satellites and for the first time revealed details about an NRO satellite launched last February aboard a Minotaur rocket. The satellite, known as Rapid Pathfinder, is equipped for taking radiation measurements in the lower Van Allen Belts. Carlson’s talk also featured a photograph of the satellite folded up in launch position. It is relatively small and unlikely to win any beauty contests, and it had been kept under wraps until now. But six months is nothing compared to the quarter century since the last GAMBIT and HEXAGON missions.

In only a few more days, we’re going to be flooded with surprises.