The uneasy state of NASA’s human space exploration programby Jeff Foust

|

| “Since it was announced, there was less enthusiasm for it among the community broadly,” Carnesale said of the asteroid mission goal. |

In the intervening three years, NASA has struggled to sell that vision of a human asteroid mission to both the space community and the general public. There remains some skepticism that it is, or should be, the goal of the agency’s human spaceflight program: they note that NASA has yet to identify—and may not yet have even discovered—the asteroid to be visited by that mission, and see little sign of preparations for it beyond the development of the Orion crewed spacecraft and Space Launch System (SLS) heavy-lift rocket. Will a new initiative expected to be in the administration 2014 budget request, due out Wednesday, change that?

Foregoing the Moon

The lack of enthusiasm about a human asteroid mission was perhaps best illustrated late last year with the release of a congressionally-mandated report on NASA’s strategic direction, performed by a committee established for that task by the National Research Council (NRC). That report concluded that there was a lack of consensus on what NASA should be doing, and, in particular, noted that the asteroid mission goal wasn’t widely accepted even within NASA. “If you ask people in the bowels of NASA, in the field offices—and we spoke with everybody from the directors of each of the field offices to college interns and everybody in between—this is not generally accepted,” Albert Carnesale, who chaired the committee, said when the report came out in December (see “What’s the purpose of a 21st century space agency?”, The Space Review, December 17, 2012).

Carnesale revisited those comments when he spoke last Thursday before a joint meeting of the NRC’s Space Studies Board (SSB) and the Aeronautics and Space Engineering Board (ASEB) in Washington. “Since it was announced, there was less enthusiasm for it among the community broadly,” he said of the asteroid mission goal. “The more we learn about it, the more we hear about it, people seem less enthusiastic about it.”

By contrast, he said, there appeared to be far more interest in a return to the Moon, leading him to conclude that such a mission might be better goal, if there was a way to gracefully back out of the president’s asteroid mission goal. “There’s a great deal of enthusiasm, almost everywhere, for the Moon,” he said. “I think there might be, if no one has to swallow their pride and swallow their words, and you can change the asteroid mission a little bit… it might be possible to move towards something that might be more of a consensus.”

Carensale’s comments echoed those of some others who have followed the development of space exploration policy in this and previous administrations. Scott Pace, director of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University and a former NASA official during the Bush Administration, has noted that there’s greater international interest in lunar exploration, which would also be more in line with the capabilities of existing and emerging space powers than an asteroid mission.

| “I don’t know how to say it any more plainly,” Bolden concluded. “NASA does not have a human lunar mission in its portfolio and we are not planning for one.” |

As Carnesale spoke, the meeting’s next speaker, NASA administrator Charles Bolden, slipped into the room. Later, as Bolden spoke, he appeared to diverge from his prepared remarks to address the interest in lunar exploration expressed by Carnesale and others. Bolden agreed that other nations were interested in the Moon, and that NASA would be happy to work with them. “I have told every head of agency of every partner agency that, if you assume the lead in a human lunar mission, NASA will be a part of that,” he said. “NASA wants to be a participant.”

However, Bolden reiterated that a human return to the Moon led by NASA was not in the cards for the foreseeable future. “NASA will not take the lead on a human lunar mission,” he said. “NASA is not going to the Moon with a human as a primary project probably in my lifetime. And the reason is, we can only do so many things.” The agency’s priority remained planning for human missions to asteroids and to Mars, he said. “We intend to do that, and we think it can be done.”

Bolden appeared to be a little frustrated that the issue appeared to be still open for debate. “I don’t know how to say it any more plainly,” he concluded. “NASA does not have a human lunar mission in its portfolio and we are not planning for one.”

Bringing the asteroid to NASA

Although NASA hasn’t offered many details about how a human asteroid mission might work, the general concept involves sending a crew in an Orion spacecraft, perhaps with an additional habitation module or other equipment, on an SLS rocket (although missions using smaller vehicles have also been proposed.) The overall trip would last anywhere from several months to a year, most of it in transit between the asteroid and Earth, with days or weeks spent in the vicinity the asteroid.

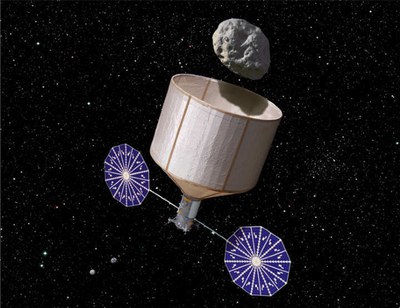

What if, though, NASA brought the asteroid to the vicinity of the Earth? That appears to be the proposal that will be included in the Obama Administration’s 2014 budget request, which will be formally released on Wednesday. In recent weeks there had been rumors, including a report late last month in Aviation Week, that funding for beginning work on such a mission would be included in the budget request.

On Friday, a key senator confirmed those plans. Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL), chairman of the space subcommittee of the Senate Commerce Committee, told reporters in Orlando that the budget would include approximately $100 million to start work on an asteroid retrieval mission. The mission would closely follow a concept in a report released last year by the Keck Institute of Space Studies (KISS) at Caltech, which examined how a small asteroid could be captured and moved to lunar orbit or a Lagrange point for an estimated cost of $2.6 billion.

| “The plan combines the science of mining an asteroid, along with developing ways to deflect one, along with providing a place to develop ways we can go to Mars,” Nelson said. |

According to Nelson, a robotic spacecraft would launch first to the target asteroid, wrapping the small body—on the order of seven meters in diameter—in a cocoon. The spacecraft’s solar electric propulsion system would gradually adjust the asteroid’s orbit, putting it into lunar orbit by 2021. Astronauts would then launch on an SLS/Orion mission—most likely the initial 2021 mission already planned by NASA and designated EM-2—and rendezvous with the asteroid in lunar orbit.

“This is part of what will be a much broader program,” Nelson said in a statement. “The plan combines the science of mining an asteroid, along with developing ways to deflect one, along with providing a place to develop ways we can go to Mars.”

The administration has been formally silent on those plans, since the contents of the budget proposal are embargoed until Wednesday morning, but some anonymous officials have confirmed to various publications that the budget proposal will include $105 million to begin work on the mission concept. The funding would be used to improve asteroid searches to help find suitable targets, begin design of the retrieval spacecraft, and work on the solar electric propulsion system it would use to move the asteroid towards Earth.

It wasn’t clear from the reports if such a mission would be in addition to, or in place of, a longer-term human mission to an asteroid in 2025. Nelson’s comments suggested the latter, as his press release stated that the mission concept would allow NASA to “advance that date by four years to 2021.”

The idea does have the support of one company that unveiled plans last year to prospect and eventually mine asteroids. “It is very exciting that NASA is considering this bold step,” Planetary Resources stated in a blog post on its website over the weekend, adding that it would be happy to help. “Public/private partnerships with NASA would allow for industry to assist in this mission, by identifying, characterizing and helping to select final targets.” (One of the founders of Planetary Resources, Chris Lewicki, served on the KISS asteroid retrieval study.)

Whether this proposal will solidify support for human asteroid missions, or simply raise eyebrows, remains to be seen. In the near term, it may help better define those early SLS/Orion missions, both the uncrewed EM-1 mission planned for 2017 as well as the crewed EM-2 in 2021. Speaking at the SSB/ASEB meeting, Bill Gerstenmaier, NASA associate administrator for human exploration and operations, indicated exactly what those missions would do, including where in cislunar space they would fly, had yet to be determined. “We’ll go somewhere in the vicinity of the Moon, in some lunar orbit, maybe to a Lagrangian point, maybe to a deep retrograde orbit around the Moon,” he said. “Depending on which missions start to materialize, what makes sense on where we want to go, we’ll pick one of those locations.”

| “NASA needs a compelling and clearly articulated goal for future human spaceflight that is consistent with its budget,” said Squyres. “That does not exist now, and it needs to.” |

Gerstenmaier said at the meeting that SLS and Orion were being designed for flight rates of one to two missions per year, but others have concerns that the actual flight rate may be much less, noting the four-year gap between EM-1 and EM-2. “There has never, in the history of human spaceflight, been a vehicle that has flown that infrequently,” said Steve Sqyures, a planetary scientist and chair of the NASA Advisory Council (NAC), at the SSB/ASEB meeting. “We are concerned that it will be difficult to maintain momentum in this program with a flight rate that is so low,” adding there would also be concerns about maintaining proficiency if SLS/Orion launches as infrequently as once every few years.

Sqyures also said that the NAC was concerned about the lack of development of other essential components of a human exploration program. “We do not have in the budget anything that will get us to a destination,” referring to landers, hab modules, or other equipment needed for missions to asteroids, the Moon, or Mars. “SLS is terrific. Orion is terrific. But NASA has been told to go places that it can’t go. And this is a big, big issue.”

Even if the administration’s proposal addresses the NAC’s concerns about low flight rates and the development of key exploration hardware components, there’s still the matter of getting the proposal sold—including adequately funded—in Congress. Congressional staffers at the SSB/ASEB meeting said it was still early in the new Congress, with many new members on key House and Senate committees who needed to be brought up to speed on space issues, but that for now there appeared to be no sign that Congress would make major changes to the NASA policies laid out in the 2010 authorization act when it takes up a new authorization bill this year. That legislation calls for the development of SLS and Orion, but did not explicitly endorse the administration’s goals and timelines of asteroid or Mars missions.

“NASA needs a compelling and clearly articulated goal for future human spaceflight that is consistent with its budget,” said Squyres. “That does not exist now, and it needs to.”

That, though, is a challenge that predates the current administration’s plans. The Vision for Space Exploration laid out a clearly articulated goal—humans on the Moon by 2020—and came up with a laundry list of reasons why to do, but it was evidently not compelling or important enough to be funded appropriately. That, ultimately, led to its replacement.

Bolden, though, warned the panels that another change in direction after the Obama Administration leaves office in January 2017 could be devastating to NASA. “I can make one promise to you: if the next administration changes course, it means we are probably, in our lifetime, in the lifetime of everybody sitting in this room, we are probably never again going to see Americans on the Moon, on Mars, near an asteroid, or anywhere,” he said. “We cannot continue to change the course of human exploration.”