Seeing the shuttles, two years after wheels stopby Jeff Foust

|

| It’s now possible for the first time since the shuttle program’s last flight for the public to see all four shuttle orbiters. |

The decisions on where the shuttle orbiters would spend their afterlives, made by NASA three months before Atlantis’s final mission, also has its share of debate and controversy. But while they jury may still be out (at least in the minds of some) of whether the decision to retire the shuttle was the “right” one—depending, of course, of how one defines “right”—one can now get a better idea of how well those decisions on where the orbiters should go turned out.

With the opening late last month of the massive new building at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex (KSCVC) hosting Atlantis, and the reopening earlier this month of the pavilion at the Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum in New York that is home to Enterprise, it’s now possible for the first time since the shuttle program’s last flight for the public to see all four shuttle orbiters. (See “Visiting the shuttles”, The Space Review, January 14, 2013, about Discovery on display at the National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center and Endeavour at the California Science Center.) Each museum displays its orbiter in a different way, offering varying perspectives on the orbiters and the Space Shuttle program overall.

Astronauts on stage for the opening ceremony of the Atlantis exhibit at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex. (credit: J. Foust) |

Atlantis

On Saturday, June 29, the KSCVC formally opened its new Atlantis exhibit to the public. The $100-million facility—paid for privately, although with a $62.5-million credit facility backed by a state agency, Space Florida—showcases the orbiter in a unique way, tilted at an angle of exactly 43.21° and with its payload bay doors open, as if the orbiter is in space (see “Bird on a wire”, The Space Review, June 24, 2013).

Atlantis’s new home got an opening as grand as the building itself. The opening ceremonies that Saturday morning, in front of the new building, featured a parade of dozens of astronauts, individually introduced by CNN reporter John Zarella, the master of ceremonies, that itself lasted 15 minutes. There were speeches from officials with Delaware North, the company that operates KSCVC, as well as KSC director Bob Cabana and NASA administrator Charlie Bolden, themselves former astronauts.

Those speeches primarily looked back on the shuttle program. “It may seem strange to you that I’m talking to a vehicle when I say, ‘Welcome home, Atlantis,’” said Bolden, who flew on Atlantis as commander of STS-45 in 1992. “It’s not like a vehicle. It’s like a person.” He said astronauts were struck by the difference in the shuttle between the terminal countdown demonstration tests—the dress rehearsals for launch on the pad—and the actual launch, when the shuttle was fueled up. “It’s breathing,” he said. “You thought you were okay, until this thing starts talking to you.”

“For most of us on this stage,” Bolden continued, referring to the astronauts who were the guests of honor for the ceremony, “it has been a dear friend, it has taken us to places that we never dreamed, and brought us safely home.”

NASA administrator Charles Bolden, who commanded Atlantis on the STS-45 mission, speaks at the opening ceremony. (credit: J. Foust) |

Officials with Delaware North hope that Atlantis will be a dear friend to them as well, triggering a new wave of tourists to the center, about an hour’s drive east of the tourist haven of Orlando. “Atlantis is greatly going to enhance the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, it’s going to enhance the landscape of Florida for tourism,” said Rick Abramson, president of Delaware North Companies Parks & Resorts.

The ceremonies wrapped up as Bolden, Abramson, and others pressed oversized “launch” buttons on the stage, triggering plumes of smoke from the bottom of the full-scale replica solid rocket boosters mounted vertically outside the exhibits, attached to a full-scale external tank. The exhibit was now open for business.

“There is literally only one word to describe what they have done here with this museum, and that is ‘Wow,’” Zarella said of the exhibit. “It is absolutely spectacular.” And “wow” might be even an understatement.

| “There is literally only one word to describe what they have done here with this museum, and that is ‘Wow,’” Zarella said of the exhibit. |

Taking a cue from the designs of theme parks that draw tourists into Orlando, visitors to the exhibit don’t simply go through the doors and see Atlantis. Instead, they first see a short film dramatizing the engineering challenges involved in building the shuttles. Then, it’s on to another antechamber, where they’re greeted with a multimedia tribute to the shuttle program, displayed on a screen in front of them and along the walls. At the end, the screen in front rises, and visitors get their first glimpse of the real thing.

Astronauts pose in front of Atlantis at the opening ceremonies for the exhibit. (credit: J. Foust) |

Atlantis’s orientation and the design of the exhibit allow visitors to look at the orbiter from many angles. The upper level, where visitors enter, offer views of the crew cabin, payload bay (including a Canadarm robotic arm extending out and above a walkway), and engine compartment. On the lower level, people can look up at the vehicle’s underside. The initial impression is stunning, as if the orbiter was indeed in space. The one drawback to this approach is that you can’t get nearly as close to the orbiter as you can with the others on display, like Endeavour in California, where people can walk underneath directly it, its belly just beyond the reach of an outstretched arm.

There is more to the facility than Atlantis itself, though. There are various other artifacts on display, including tires from the STS-135 mission and a replica of the Hubble Space Telescope. Kids can crawl through scale models of International Space Station modules suspended from the ceiling, and the lower level features various simulators to try your hand at landing a shuttle or using the shuttle’s robotic arm. The Shuttle Launch Experience, built several years ago as a standalone theme park-style ride (see “Review: Shuttle Launch Experience”, The Space Review, April 28, 2008), is now incorporated into the Atlantis exhibit as well. The result is a tribute to the Space Shuttle program similar to the Apollo Saturn V Center at KSC, but on perhaps an even grander scale.

The first view visitors of the exhibit get of Atlantis as they emerge from a film and multimedia presenattion. (credit: J. Foust) |

Enterprise

Of all the shuttle orbiters, Enterprise and its assignment to the Intrepid Museum in New York is perhaps the most controversial. The Smithsonian was effectively guaranteed an orbiter, and few would begrudge KSC, the launch site for those 135 missions, from getting one as well; even Los Angeles made sense as both a West Coast location and because of Southern California’s history in building and maintaining the orbiters.

But when NASA announced New York would be getting Enterprise, a hand-me-down from the Smithsonian as it took delivery of Discovery, there were howls of protest, particularly from Texas and Ohio, who believed either Houston, home of the Johnson Space Center, or Dayton, whose National Museum of the Air Force was long thought a frontrunner, would be better choices. That decision is still a sore point, particularly in Houston, even after a NASA Inspector General report found no evidence of political influence on the decision-making process. When Space Center Houston announced plans recently a for a “name the shuttle” contest for the full-scale replica it received last year, one Houston publication complained that “being bypassed for one of the shuttles in the city that literally built them was a particularly potent kick in the crotch.” (Nevermind, of course, that the shuttles were not “literally built” in Houston.)

Those complaints gained a degree of weight after Enterprise arrived in New York last summer. Enterprise was placed on the flight deck of the retired aircraft carrier inside a temporary inflatable structure as the museum worked to raise money for a permanent facility across the street. But when Hurricane Sandy struck New York last October, flooding knocked out power to generators, deflating the structure and leaving the shuttle partially exposed to the elements, with minor damage to its tail. Couldn’t New York treat their orbiter better, some wondered?

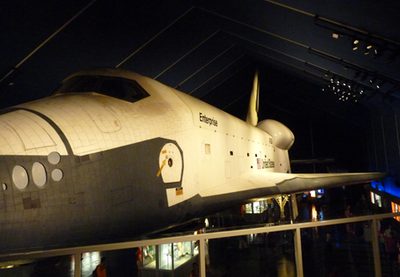

Enterprise is now housed inside a structure on the aft portion of the deck of the retired carrier Intrepid. (credit: J. Foust) |

The new Space Shuttle Pavilion on the Intrepid flight deck should ease those concerns. The structure formally opened on July 10 with much less pomp and circumstance than its Florida counterpart: rather than the NASA administrator, the event featured the director of education for NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, as well as museum officials and a city councilman. But the exhibit itself features plenty of substance.

| One element of the overall Enterprise exhibit is, perhaps unintentionally, a little bittersweet. |

Gone is the original inflatable structure, replaced with a more solid, windowless structure on the aft portion of the flight deck; at the very least, it looks far sturdier and better able to handle the elements. Upon entering, visitors have an opportunity to have their picture taken with one of the more iconic images of Enterprise’s arrival in New York as the backdrop: the shuttle and its 747 carrier aircraft flying over Manhattan. Visitors then pass through a short corridor playing audio transmissions from Enterprise’s approach and landing tests from the 1970s.

Then it’s on to Enteprise itself. The shuttle is displayed at a slight angle to the horizontal, as if it was in the process of landing: the nose gear is just off the ground, with the orbiter’s weight there instead supported by struts. Visitors can, like Endeavour, walk underneath Enterprise, as well as see it nose-to-nose from a viewing platform immediately in front of the orbiter.

Enterprise is displayed with its nose landing gear off the ground, as if captured in the process of landing. (credit: J. Foust) |

There are other artifacts on display in the pavilion, such as instrument panels from the flight deck of Enterprise and small-scale models of the shuttle used for early wind tunnel tests. Those artifacts include a major non-shuttle item: a Soyuz descent capsule purchased by space tourist Greg Olsen and donated to the museum; the small size of the capsule stands in stark contrast to the orbiter overhead. There’s also a short film about the Space Age and the development of the shuttle, narrated by actor Leonard Nimoy.

The exhibit—which required a separate ticket in addition to general museum admission, bringing the total cost for an adult to $31—certainly has a greater degree of permanence that the earlier one. Inside, you can quickly forget you’re on the deck of an aircraft carrier, thanks to the opaque walls (and, fortunately on a hot, humid day, the air conditioning.) The museum still has plans for a permanent facility off the ship for Enterprise, but has announced no specific schedule for building it. It’s likely this pavilion will be Enterprise’s home for at least several years. If so, it should be in good hands.

One element of the overall Enterprise exhibit is, perhaps unintentionally, a little bittersweet. Several displays show ads, letters, and other items from the late 1970s, when Enterprise was going through its tests and the Space Shuttle program overall had the promise of making space access more routine. One 1977 ad from a company involved in the program showed a young man and woman looking at a scale model of a shuttle. “In the years to come Bill and Linda may fly in a real Space Shuttle… and Armco materials will go along,” claims the ad’s headline. Later, the ad copy states, “Well before the century ends, thousands of men and women will have shared these vehicles’ tasks in the sky… In short, the Shuttle will make space flight pay off.”

An ad from 1977 shows the promise of routine access to space that the Space Shuttled offered in that era. (credit: J. Foust) |

The Space Shuttle, of course, fell short of those lofty hopes and dreams. Bill and Linda probably didn’t fly in a shuttle, unless they defied the long odds of becoming astronauts, and thousands of people have yet to fly in space. That’s a message worth remembering as the shuttles are in their public retirement. It should not, though, detract from the achievements they did accomplish in their 30 years of flights. Perhaps both those achievements and those dreams left unfulfilled, embodied in the four orbiters on display, can inspire a new generation of engineers, scientists, and explorers to turn those visions of the future into reality.