International cooperation and competition in space (part 2)How—and why—should the United States proceed?by Cody Knipfer

|

| Looking at historical and projected trends, NASA’s budgetary limitations suggest that a unilateral return to the Moon and journey to Mars is highly unlikely. Partnership of some form seems apparent as the most practical course of action. |

The prospect for international cooperation intersects with these goals in complex and overlapping ways. Cooperation toward one may bolster—or, conversely, undermine—progress toward another, hence the need to strike an appropriate balance. This is perhaps most apparent in the interplay between pursuing exploration beyond Earth orbit and fostering commercial space capabilities, to which we turn first.

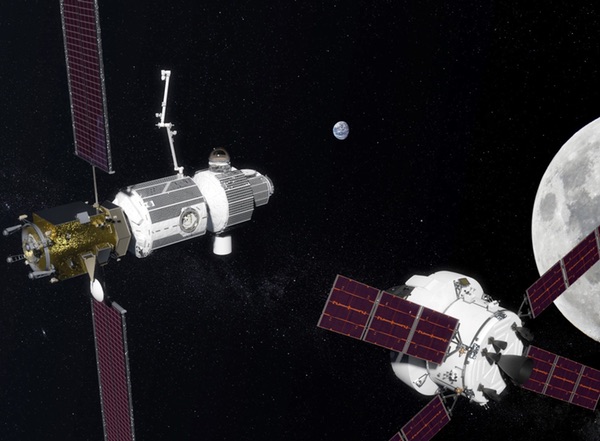

Looking at historical and projected trends, NASA’s budgetary limitations suggest that a unilateral return to the Moon and journey to Mars is highly unlikely. Partnership of some form seems apparent as the most practical course of action. While a cislunar “proving ground” period of human spaceflight has been a component of the United States’ exploration roadmap since the Obama years, the Trump Administration’s suggestion of a pivot back to the Moon, and NASA’s recent proposal of the “Deep Space Gateway” (DSG) cislunar station, has ignited a recent flurry of commercial and international interest in collaboration with NASA to support that objective.

Russia has proposed a Lunar Mission Support Module that would attach to the DSG, giving the outpost extra life support, berthing, and storage capabilities. The European Space Agency has plans for its own habitat and logistics module to attach to the DSG, which it hopes to service with a European cargo spacecraft. Canada has proposed both a robotic arm, like that used on the International Space Station, and a solar sail demonstrator to fly on or near DSG. Japan hopes to leverage the DSG to conduct human landings on the Moon in the 2030s.

Meanwhile, SpaceX and Blue Origin hope for commercial cargo contracts to the DSG. A host of companies touting lunar landing capabilities, including Blue Origin, Astrobotic, and Masten, seek to support the DSG with on-surface operations, and several firms are working on the NASA NextSTEP solicitation to provide, through private-public partnership, a DSG habitat and power module.

Of course, though NASA has the mandate to pursue exploration beyond Earth orbit, the DSG is still nothing more than a concept. As the maxim goes, budgets are policy, and the DSG is currently unfunded (even if NASA is deep in talks with industry and international partners about it.) Still, it provides a conceptual launching point to consider the arrangements that cooperation can be pursued for the human exploration program.

First is the question of the critical path. By involving international contribution as core elements of the DSG—or whatever project ultimately gets funded—the United States could reap considerable cost savings by prioritizing development in its core competencies. International partners are discussing providing critical capabilities such as habitation, power, and life support which, if pursued, would allow NASA focus on furnishing a core module along with launch and astronaut delivery. This type of deep integration would surely necessitate complex, long-term agreements and programmatic decision-sharing with partners. Considering the United States’ lack of political consistency on long-term, ambitious space projects over the past few decades, this may bring much needed political stability and buy-in for executing exploration beyond Earth orbit.

This sort of integration would, in effect, establish an arrangement akin to the International Space Station. This is an important consideration, as it would affect future programmatic decisions. At the point when the United States is ready to proceed with its mission to Mars, would its partners be ready to step away from the DSG? NASA has proposed that the DSG be capable of moving orbits to support exploration goals, but consulting with partners and securing their approval for each maneuver would likely be a complex, time-consuming process. The challenges of the International Space Station, seen especially in the continuing struggle to decide on its future and fate, foreshadow the difficult questions that may come with partnership on the DSG. And what of the risk of schedule slippage? ESA’s continuing issues with producing the Orion spacecraft’s service module is an omen of potential slips that could occur by relying on international partners to provide necessary components to the DSG. For a project with already high costs (and a need to maintain consistent launch cadence with the Space Launch System to keep its launch costs down), any slippage could threaten to derail NASA’s exploration timeline.

Finally, would this arrangement present opportunity for the United States’ commercial industry to offer core contributions? Drawing on the example of the ISS, it seems so: NASA could enter into contracts for cargo and astronaut delivery or, in the example of Bigelow’s BEAM, extra habitation space. However, if commercial is to play a supporting, rather than critical, function for the DSG, would the demand for its support be robust enough to involve several commercial partners and foster strong development in the industry? Maybe. This will depend on the level of reliance upon international contribution to the station and the level of funding NASA is willing and able to allocate to commercial services.

Surely, though, many in the industry will feel snubbed if NASA decides to utilize the European or Russian modules for extra storage space or the European cargo spacecraft for its cargo deliveries in lieu of American companies with the same capabilities, even if it is cheaper to do so. For NASA’s leaders, finding the appropriate arrangement that maximizes cost-savings, leverages international capabilities, while still leaving opportunity for commercial involvement will be a delicate and difficult balancing act.

With that addressed, we turn to two areas where space competition should and likely will remain strategically important: the commercial and national security space sectors.

| For NASA’s leaders, finding the appropriate arrangement that maximizes cost-savings, leverages international capabilities, while still leaving opportunity for commercial involvement will be a delicate and difficult balancing act. |

First, the commercial sector. To increase the competitiveness of its space industry against foreign companies and service providers, the US government can pursue domestic several strategies that lower the barriers and costs to doing business. These include reform and easing of export control regulations, such as ITAR, to allow companies to sell high tech items, currently deemed “sensitive,” to foreigners and to offer services such as launch from abroad. Likewise, regulatory and licensing processes can be simplified and streamlined, particularly for remote sensing activities and launch. Both have long been sought by the US commercial space industry and, gradually, both are making progress, especially with the American Space Commerce Free Enterprise Act, which broadly overhauls commercial space licensing and authorities, currently working its way through Congress.

The government can also consider offering incentives, be it in the form of tax credits, direct investment, or a more permissive regulatory environment, to entice space companies to do business in and from the United States. This strategy has seen success abroad, especially in Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia, and to a degree in China, which offers bundled and subsidized satellite construction and launch services—all representative of the growing international competition for leadership in commercial space.

Of course, business anywhere requires a predictable legal environment and a relatively secure physical environment—especially so for business in space, where costs of entry, and of failure, are high. Uncertainties such as questions over the legality of space property rights and the issues of space traffic management, space debris, and space weather pose challenges for the global commercial space sector, not to mention civil and national security space programs. Is it in the interest of the US to pursue international cooperation as a solution to these issues? Keeping in mind the value of norm- and regime-building, cooperation would seem to allow for a stable environment in which its commercial space sector could more securely operate. Yet doing so would also enable opportunities for foreign commercial space ventures to more readily compete. Still, considering that maintaining a secure space environment is a policy goal for the United States, it is evident that international cooperation on these problems is indeed the best strategy for American policymakers.

How, then, might cooperation be pursued for these issues? One case is the legality of space property rights. Through recognizing, in the 2015 Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, the right for American citizens to own material mined in space, the United States has set in motion a precedent for space property rights, one with which many in the international community disagree. Legitimate questions exist about mining in the context of the non-appropriation provision of the Outer Space Treaty, though the United States has long maintained that the two are mutually compatible. Other countries, particularly Luxembourg, have begun to establish their own legal frameworks enabling space mining and private space property rights.

To that end, the United States can pursue (and has) high-level multilateral dialogue on issues pertaining to space mining and its legality. These could include memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with countries about non-interference in mining activities and environmental protections. By simply allowing such operations to go forth while regulating and supervising them in a responsible manner, the United States could begin to establish norms of best practice. Ultimately, the legality of space property rights may require a new international treaty, although pursuing this option, at least in the short- to mid-term, is a non-starter.

With space situational awareness, the United States has made—and should continue to seek—good progress establishing data-sharing agreements with partners to enhance the tracking of objects in space. Considering that the United States Air Force already provides tracking information and warnings to operators across the world, continuing cooperation to integrate global monitoring systems and data more deeply into trajectory calculations is an obvious course of action. Yet the discussion of space situational awareness often evolves into one of space traffic management, which is a far more complicated arrangement. Consideration of this may be premature, as the United States has not yet established an authority to manage space traffic (proposals have been floated of giving it to the FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation), though early thoughts are warranted nonetheless.

| Should the United States be compelled to move a surveillance satellite, for example, or an American company to move their communications satellite because an international organization tells them to? |

To be truly effective, a space traffic management system must have global reach and be capable of compelling operators to maneuver if needed, akin to air traffic control. Should the United States content itself with allowing countries to pursue their own space traffic management systems and be responsible only for the operators within their jurisdiction? If so, working to establish an international coordinating body that normalizes countries’ space traffic management regimes—perhaps analogous to ICAO in aviation—could be an approach toward an effective system.

Yet in that approach, or in standing up an international regulatory body with powers of compulsion, the United States risks both its own national security and economic competitiveness. Should the United States be compelled to move a surveillance satellite, for example, or an American company to move their communications satellite because an international organization tells them to? Doing so would represent cooperation in managing space traffic, yet is a clear example of the potential drawbacks of such cooperation. These are questions for future years, which will be informed by the organizations, processes, and procedures that will evolve to execute the role. Nonetheless, the impending difficulty policymakers will have striking a balance between cooperation and competition on space traffic is clear to see.

There is then the issue of space debris, where striking a future balance between cooperation and competition will likewise be complex. Through international forums such as the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordinating Committee, the United States has done well promulgating its orbital debris mitigation standards internationally; the same is true with gradual work on the UN Guidelines on the Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space. However, with satellite mega-constellations soon to fly and a considerable number of defunct satellites stuck in long-duration orbits, many anticipate debris removal and remediation being an eventual necessity to deal with the space debris issue.

The 2010 National Space Policy directs NASA to begin development of active debris removal (ADR) technologies, though, as Brian Weeden of the Secure World Foundation points out,

“Minimal progress has been made on developing ADR technology. The initial interest shown by the DOD has waned, and NASA has decided it will not pursue R&D of ADR technologies beyond some very limited low-level efforts… [i]t is believed that the main reason for this limitation was an unwillingness by NASA to take on a potentially costly major new initiative without additional funding from Congress.”1

Significant legal and economic, not to mention funding, challenges confront the feasibility of active debris removal. Because space objects, including debris, are permanently within the jurisdiction of the state to which they’re registered, government permission will be required to interact with and remove any space object and governments will be legally liable for any damages that occur because of ADR activities. To that end, it would seem reasonable for the United States to pursue dialogue with other states about establishing transfer-of-ownership agreements and conventions on the liability of debris removal, establishing a normative or legal regime for space debris removal. This could come done in several ways: through MOUs and high-level discussions, or through a cooperative civil mission with other states.

A cooperative civil mission between governments would come with several of the benefits identified in space cooperation, driving down costs and risk for technology development and execution on the part of each partner (which, as Weeden noted, are currently a prohibitive factor) and establishing norms and expectations of debris removal practices by fiat. However, several companies have interest in—and identified prospective competitive business cases for—active space debris removal. Meanwhile, the technologies used for debris removal are inherently “dual-use,” in that they can be used to deorbit functional satellites just as well as debris. Whether the United States can justify this potential risk to its space security will be informed by the level of trust and military cooperation it holds in the potential partners with which it could collaborate.

Ultimately, the decision on whether the United States should actively pursue an international program or simply strive to establish enabling norms for debris removal will come down to how policymakers weigh the merits and utility of a government-to-government partnership against national security considerations and turning over the potentially profitable activities to its commercial sector.

| So long as other countries have counterspace capabilities beyond kinetic hit-to-kill vehicles, the United States cannot afford to tie its hand in protecting its space assets. |

Finally, we turn to cooperation and competition in the use of space for national security. Space will continue to be used to more closely support warfighting operations on Earth, and it intuitively makes sense for the United States to pursue cooperation and integration with its military partners to increase mutual capabilities. The real question for cooperation is whether direct competition in space (i.e. it becoming weaponized and a theater of war, not for war) can, through TCBMs or other agreements, be prevented.

This is a topic in and of itself, yet some high-level observations can be made. Foremost is that any agreement must preserve the United States’ national security interests and capability to protect its space assets—including, if needed, through retaliation. This is, of course, spelled out in the 2010 National Space Policy. To that end, any agreements, be they through international forums such as the United Nations Conference on Disarmament or on a state-to-state basis, need to be transparent, verifiable, enforceable, and genuinely allow for protection of space assets from destructive attack.

Current proposals toward that end, such as the Chinese/Russian proposal to ban anti-satellite weapons is, are lacking in enforceability and verifiability, as frequently noted by American national security leaders. So long as other countries have counterspace capabilities beyond kinetic hit-to-kill vehicles, the United States cannot afford to tie its hand in protecting its space assets. That said, some approaches may work: for example, the United States could pursue agreements on preventing use of weapons, be they kinetic or not, that would create undue amounts of space debris during an attack. A cooperative agreement of this sort would still allow for some level of protective retaliation in the event of an attack, while having the added benefit of protecting the space environment should conflict erupt in space.

In the meantime, the United States can continue to consider or pursue scientific or exploratory cooperation with potential adversaries in space in order to build mutual trust, reinforce norms of good behavior, and open channels for space dialogue and understanding, which may mitigate the possibility of unintended miscalculations and military escalation in the space domain should a crisis on Earth break out.

On cooperation with China

This leads into oft-debated subject in the field of space cooperation: potential partnerships between the United States and China. At present, NASA is forbidden by law from cooperating with the Chinese bilaterally in space, and any potential partnership in the future would first require a change in that statute. Is the utility of space cooperation with China, compared to the drawbacks, strong enough to warrant that?

First, a look the drawbacks. The most frequently cited issue is the national security risk that cooperation with the Chinese could entail. It stands to reason that, as international partnerships in space involve the exposure and sharing of US technology and information, China would acquire and benefit from American technology. As space technology often carries dual-use benefit, cooperating with the Chinese risks sacrificing the United States’ technological advantage and thereby compromises its national security—an important consideration, given that China, to many in the national security field, represents the United States’ greatest space threat.

| Joint efforts of scientific value, such as monitoring climate change or space weather, could benefit both countries both diplomatically and in the pursuit of the goal of a secure space environment. |

Next, does China have anything to offer to a project that would equitably match and benefit the United States’ contribution? For more sophisticated projects such as human spaceflight, there is a presumption that the United States’ competencies are far greater than China’s. As such, the United States would likely contribute more money or greater capabilities to a project. If this is the case, the relative benefits of cooperating are much greater for China than for the United States. Unless there is substantial diplomatic utility to the project, cooperation on most high-profile projects wouldn’t seem to advance the United States’ competitive advantage in space and therefore isn’t reasonable.

What of the diplomatic utility, though? As noted, working with the Chinese in space would present the United States with an opportunity to learn their standard operating procedures and decision-making processes. This would be valuable toward limiting misunderstanding or miscalculation among American policymakers, as it would allow them to more accurately determine and decipher China’s intended use of dual-use space technologies. Space cooperation between the two countries would also signal—and, over time, establish—growing trust and confidence between them. During a time of tension on Earth, coming from a perspective of presumed good intention would better mitigate miscalculation or escalation in space than the current status quo.

To that end, a cooperative venture with China need not be expensive or high-profile. Joint efforts of scientific value, such as monitoring climate change or space weather, could benefit both countries both diplomatically and in the pursuit of the goal of a secure space environment. These could come in the form of programmatic cooperation, such as flying instruments on each other’s satellites, or in the sharing of already collected data. With both countries interested in lunar activity, sharing data about lunar conditions and lunar surface composition could help create meaningful patterns of interaction that lower barriers to information exchange—and which may pave the way to further cooperation.

Of course, engagement will need to be strongly conditioned on transparency, limited in expectations, and involve consultation with the United States’ current allies. Ultimately, as Listner and Johnson-Freese point out, “[w]hether outer space cooperation with China will… become a reality will be a political decision, and that decision must be made by considering both the globalist and geopolitical viewpoint when weighing the pros and cons.”2

Concluding suggestions

This piece has provided a high-level review and assessment of the utility and drawbacks of space cooperation and competition, along with their general implications for the United States’ broad space policy. While specific decisions on whether to pursue partnerships in space, and on what programs and issue areas, will be made on a case-by-case basis weighing utility versus drawbacks, several general conclusions about space cooperation and competition can be drawn:

- At its best, programmatic space cooperation provides each partner with capabilities they themselves do not have, minimizes their individual cost burdens, and equitably advances their policy goals. Depending on the partnership’s arrangement, however, countries may become beholden to, and responsible for, others’ struggles with schedule or cost.

- Space cooperation pursued for diplomatic purposes should support foreign policy objectives. While cooperation in space may not drive relations on Earth, it is a valuable tool for establishing channels of dialogue and building mutual understanding.

- Cooperation, especially in the form of TCBMs, multilateral agreements, and norm-building, can be used to support benign competition (such as enabling opportunities for commercial activity) and temper malignant competition (such as in-space use of hostile force.)

- As the commercial sector becomes more vibrant, policymakers will need to weigh the utility of cooperation with the international community against the utility of cooperation with the private sector. Both offer different, and occasionally disparate, benefits. Depending on the policy objectives of a program, the utility of one will outweigh the utility of another.

To close, here is a short- to mid-term programmatic proposal, pursuing, in conjunction with the Deep Space Gateway, the “Moon Village” concept laid out by ESA. The Moon Village is envisioned as an open collaborative effort on a lunar base that could support a mix of civil and commercial research, tourism, and economic activity such as mining and be a springboard for deeper human exploration of the solar system.

European contributions to the DSG could be solicited as supporting the Moon Village through capabilities such as tele-robotics terminals, human-rated lunar landers, or modules to store supplies for the lunar surface, while NASA focuses on the “critical path” of developing DSG’s primary habitation and power modules and furnishing launch. Commercial operators could be given the role of resupplying the DSG, with partners developing redundant capability for their own use if needed. In leveraging the “gateway” aspect of DSG, the station could be used as a platform to travel to and from the Moon.

| Policymakers will need to be smart in the challenging tasks of balancing between potential partners, in maximizing the utility of partnerships, and in pursuing the projects that best advance their national interest. Ultimately, doing so will be far preferable than going it in space alone. |

At the Moon Village, commercial operators could perform a host of functions to support research goals, such as landing instruments and running experiments for the space agencies, while also carrying out their own activities, such as lunar mining. If in situ resource extraction becomes practical, over time the Moon Village could be used to produce fuel and a fuel depot to store it could be attached to the DSG. As the Moon Village is envisioned as openly collaborative, China, which has lunar interests of its own, could be invited to participate, carrying out its own research and activities while making use of, and contributing to, the Moon Village’s supporting infrastructure.

The arrangement of this proposal seeks to maximize the value of international cooperation, minimize its drawbacks, and balance between all potential partners. By having NASA focus on the DSG’s critical path, it minimizes the risk of schedule slippage on the actual hardware; European contributions would be ancillary to core DSG functions. However, as the Moon Village would be deeply integrated into the cislunar program, European contributions would still be critical to the overall endeavor. The Moon Village, meanwhile, would present robust opportunity for commercial activity. By having commercial operators conduct lunar mining there, in addition to supporting government needs, normative buy-in could be secured on the principles of space mining and resource extracting. Moreover, if it becomes a facility for in-space fuel production and a facility to practice and experiment with long term on-surface operations, it would be a lasting launching point for eventual missions to Mars. And finally, by providing opportunity for constructive Chinese participation, meaningful channels of dialogue could be established along with mutual confidence-building in the responsible use of the lunar surface.

Whether an arrangement akin to this will be considered or pursued remains to be seen. Yet what is certain is that cooperation—and competition—will continue to define the activities of states in outer space for years to come. Policymakers will need to be smart in the challenging tasks of balancing between potential partners, in maximizing the utility of partnerships, and in pursuing the projects that best advance their national interest. Ultimately, doing so will be far preferable than going it in space alone.

Bibliography

Anatoly Zak, “NASA, international partners consider solar sail for Deep Space Gateway,” Planetary Society, September 25, 2017.

Anatoly Zak, “Russia proposes Lunar Mission Support Module for Deep Space Gateway,” Russian Space Web, November 2017.

Brian Weeden, “US space policy, organizational incentives, and orbital debris removal,” The Space Review, October 30, 2017.

Christopher Johnson, “Policy and Law Aspects of International Cooperation in Space,” American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2001.

D.A Broniatowski, G. Ryan Faith, and Vincent G. Sabathier, “The Case for Managed International Cooperation in Space Exploration,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2006.

Dean Cheng, “U.S.-China Space Cooperation: More Costs Than Benefits,” The Heritage Foundation, October 30, 2009.

Dean Cheng, “Prospects for U.S.-China Space Cooperation,” The Heritage Foundation, April 9, 2014.

Eligar Sadeh, James P. Lester & Willy Sadeh, “Modeling International Cooperation for Space Exploration,” Space Policy 3 (1996), pgs. 207 – 223.

“Fact Sheet: National Security Space Strategy,” 2011.

Frank A. Rose, “Using Diplomacy to Advance the Long-Term Sustainability and Security of the Outer Space Environment,” March 3 2016.

James Clay Moltz, “Preventing Conflict in Space: Cooperative Engagement As a Possible U.S. Strategy,” Astropolitics 2 (2006), pgs. 121 – 129.

Jeff Foust, “Japan has plans to land astronauts on the moon by 2030 -with a little help from the United States,” SpaceNews, June 29, 2017.

Jeff Foust, “The Role of International Cooperation in China’s Space Station Plans,” SpaceNews, October 14 2014.

Jesper Poulssen, “Rivals and Cooperation in Outer Space,” Leiden University, September 2016.

Kenneth S Pedersen, “International Cooperation and Competition in Space: A Current Perspective”, 11 J. Space Law 21 (1983).

Leonard David, “Europe Aiming for International ‘Moon Village’,” Space.com, April 26 2016.

Michael Listner and Joan Johnson-Freese, “Two Perspectives on U.S.-China Space Cooperation,” SpaceNews. July 14, 2014.

NASA Policy Directive 1360.2B, “Initiation and Development of International Cooperation in Space and Aeronautics Programs,” August 2014.

“National Space Policy of the United States of America,” June 28 2010.

Robert Pfaltzgraff, “International Relations Theory and Spacepower,” National Defense University, May 2013.

Scott Pace, “Align U.S. Space Policy with National Interests,” SpaceNews, March 2015.

Stephen Krasner, eds. International Regimes (Ithaca, 1983).

Stephen Whiting, “Space and Diplomacy: A New Tool for Leverage,” Astropolitics 1 (2003), pgs. 54 – 77.

Tereza Pultarova, “European space officials outline desired contribution to Deep Space Gateway,” SpaceNews, October 26, 2017.

Endnotes

- Brian Weeden, “US space policy, organizational incentives, and orbital debris removal,” The Space Review, October 30, 2017.

- Michael Listner and Joan Johnson-Freese, “Two Perspectives on U.S.-China Space Cooperation,” SpaceNews. July 14, 2014.