A different trajectory for funding space science missionsby Jeff Foust

|

| “Can we design a low-cost privately-funded mission to Enceladus, which can be launched relatively soon and that can look more thoroughly at those plumes to try to see what’s going on there?” Milner asked last year. |

That increase is due in large part to the actions of Rep. John Culberson (R-TX), chairman of the appropriations subcommittee that funds NASA. Culberson has been the biggest Congressional advocate of planetary science in recent memory. That’s included a particular emphasis on missions to Jupiter’s moon Europa (see “The end of an era in the exploration of Europa”, The Space Review, this issue.) That rising tide, though, has lifted other planetary boats.

That funding trend may soon change. Culberson lost reelection last week; his challenger, Lizzie Pannill Fletcher, used his interest in Europa to suggest Culberson was out of touch with the needs of his Houston-area district. “John Culberson’s ideas are out of this world. He wanted NASA to search for aliens on Europa,” said one ad critical of Culberson, funded by a political action committee backing Fletcher. “For Houston, Lizzie Fletcher will invest in humans, not aliens.”

But even in the best of times, there are more good ideas for missions than funding available. Competition for relatively low-cost Discovery-class missions, and medium-scale New Frontiers missions, remains fierce. Advancements in the capabilities of low-cost small satellites may soon put planetary missions in the range of alternative funding sources, be they consortia of organizations or individual philanthropic benefactors.

A quiet Breakthrough to Enceladus

Culberson’s interest in Europa is based on the commonly held belief that the icy moon, which harbors a subsurface ocean of liquid water, may be potentially habitable. Europa, though, is neither the only such world in our solar system nor necessarily the most promising.

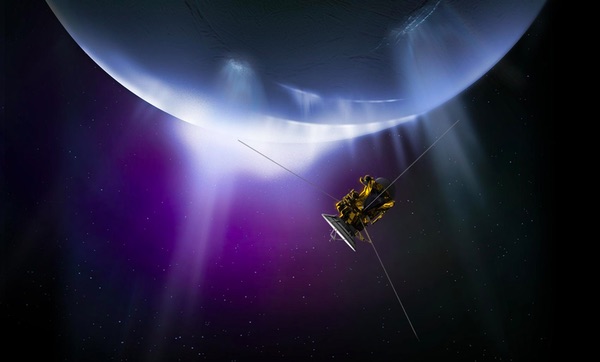

Some planetary scientists and astrobiologists are more intrigued by Enceladus, the moon of Saturn that also is believed to have a subsurface ocean under its icy surface. Observations by the Cassini mission showed that Enceladus also has plumes erupting from its surface on a regular basis, allowing a passing spacecraft to sample that interior. Europa may also have plumes, but the evidence for them, based largely on Hubble observations, is far less clear-cut.

The moon has attracted the interest of the Breakthrough Prize Foundation, the organization established by Russian billionaire Yuri Milner and best known for the prizes it awards annually. It has also backed Breakthrough Listen, a ten-year, $100-million search for extraterrestrial intelligence effort (see “A funding breakthrough for SETI”, The Space Review, August 17, 2015), and Breakthrough Starshot, a concept for laser-propelled “lightsails” that could travel to nearby star systems (see “A starshot into the dark”, The Space Review, April 18, 2016).

A year ago, Milner said that his foundation was interested in supporting a mission of some kind to either Europa or Enceladus. “Can we design a low-cost privately-funded mission to Enceladus, which can be launched relatively soon and that can look more thoroughly at those plumes to try to see what’s going on there?” he said during an event in Seattle organized by The Economist last November.

| “We think we can do those missions for tens of millions, not hundreds of millions or billions,” said Worden. |

Pete Worden, the former director of NASA’s Ames Research Center who now runs the Breakthrough Prize Foundation, confirmed that the foundation had been looking at such missions. “We did an initial study,” he said during the NewSpace Europe conference last November in Luxembourg. “We met with our sponsor, Mr. Milner, in August and said we could probably do it, using more conventional means, for a few hundred million dollars.”

That was, apparently, too expensive even for Milner. “So he sent us back to look at interesting lower-cost efforts, and we found a few,” Worden said last year. That included the potential use of solar sails to help propel the mission.

At the time, Worden said the foundation was preparing to start a six-month study to look at those concepts. “Hopefully, later this next year, if it looks good, we’ll be off and running,” he said then.

The foundation said little more about the proposed mission until August. Worden, appearing on a panel at a space conference at Arizona State University, mentioned in passing that the foundation had secured an agreement with NASA to support mission studies. “This week we signed an agreement with NASA to look at a privately funded mission that will work with NASA that will go to the outer solar system and look for life either on Enceladus or Europa,” he said at the August 20 event. “We think we can do those missions for tens of millions, not hundreds of millions or billions.”

NASA didn’t comment on the agreement at the time, and a spokesperson for the foundation said in August that Worden’s comments were premature: the agreement had not yet been signed.

However, NASA and the Breakthrough Prize Foundation did sign an agreement, in the form of an unfunded Space Act Agreement, in September. That agreement, posted without fanfare on a NASA website recently, describes how NASA will support work on “pre-Phase A” studies of a proposed mission to Enceladus. That included, according to the agreement, providing scientific and technical expertise through various reviews running from March to December of 2019.

The agreement says little about the mission itself, other than it would be a “life signature mission” that could make use of solar sails, as Worden hinted at last year. Neither the foundation nor NASA responded to requests for comment last week.

Milner, appearing at his foundation’s annual prize ceremony November 4 at NASA Ames, again indicated his foundation was interested in studying missions to Enceladus or Europa, but didn’t mention the new agreement with NASA. “We’re thinking, within our foundation, is there something we can do, privately funded, which will supplement the government-funded projects?” he asked.

Lisa Callahan, Lon Levin, and Jim Bell discuss the formation of the MILO Institute during a presentation at the International Astronautical Congress in October. (credit: J. Foust) |

Asteroid de MILO

Milner, if he does go through with a mission to Enceladus, will likely fund the mission primarily himself, although Worden previous hinted that the foundation would be open to working with NASA or ESA on such a mission.

That approach, though, isn’t the only unconventional approach under consideration for planetary science missions. “I learned two things by being on the board of The Planetary Society. First, how brilliant our space scientists are,” said Lon Levin, president and CEO of GEOshare. “The second thing I learned about space scientists is how good they are about whining about not having enough money in their budgets.”

Levin was speaking at an event during the International Astronautical Congress (IAC) in Germany last month that formally announced the creation of the MILO Institute, a new venture that seeks to address that second thing Levin learned by coming up with new approaches for funding planetary missions.

| “The second thing I learned about space scientists is how good they are about whining about not having enough money in their budgets,” Levin said. |

The institute, he said, had roots in discussions at Arizona State about taking a more entrepreneurial mindset to supporting missions. “Why does the model have to be just the government making these decisions who then hands the money out to various universities?” he said.

Levin cited three trends supporting the development of the new institute. One is the rise of space agencies around the world by countries that increasingly see space as part of their economic development. A second factor is a desire to provide hands-on opportunities for students interested in engineering careers. The third factor is the amount of “compelling science that is just not getting done,” he said, because of a lack of funding.

“The new model is pretty straightforward and simple: rather than government-to-government, how about universities throughout the world get together,” he said, “and they can all share the cost as well as the science.”

The institution, he said, will have three goals for carrying out its missions: performing “compelling science” that is of interest to participating universities, have mission costs of no more than $200 million, and schedules that allow the missions to be completed on under a decade.

“The thing I have really pushed for, the drum that I beat as part of this project, is absolute top-quality science, what I call decadal-survey-quality science,” said Jim Bell, professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State and president of The Planetary Society. “We want these missions that we do to be making discoveries, not just doing something that’s been done before.”

Bell, also speaking at IAC, said the group forming the institute brainstormed ideas for an initial mission. The concept they settled on a concept called NeoShare to visit several near Earth asteroids.

“Our inaugural mission is a set of small spacecraft, smallsats or maybe cubesats,” he said. “About a half dozen of them will encounter six or more near Earth asteroids, relatively close to the Earth.” With about 100 potential targets to choose from, Bell said such a mission could “sample the diversity” of such objects, roughly doubling the number of such bodies visited by spacecraft.

The details of the mission have yet to be fleshed out. Lockheed Martin has agreed to work with the institute on mission concepts. “We’ll be working to describe the mission architecture, to put together a spacecraft architecture and design for a set of spacecraft that could support that mission,” said Lisa Callahan, vice president and general manager for commercial and civil space at Lockheed Martin.

The institute is, meanwhile, lining up potential partners for the NeoShare mission. “The interest has been impressive,” said Levin. He listed a mix of companies, universities and agencies, mostly smaller organizations less well known in the space field, from the University of New South Wales – Canberra to the Mexican Space Agency.

Those partners would play varying roles, and pay corresponding costs for that participation. “We’re asking different universities around the world to pay what they can afford,” Levin said. “They’ll choose whether they want to have a leadership role in MILO, which would cost a certain amount, or if they just want to build a sensor, which is less. There will be a whole pay scale that will add up to $200 million, or even more based on the responses that we’re getting.”

| “There is that risk,” Bell said. “It may or may not work. We’re going to test it.” |

The unusual name of the institute is an artifact of earlier studies, Levin said. When planning for what became the MILO Institute started a year and a half ago, one mission concept under consideration was a mission to Venus. While that turned out to be too expensive, the name “MILO”—as in Venus de Milo—stuck as the name of the organization. (Despite the all-caps name, it is not an acronym, he added. “I know this is extraordinary in the space science community,” he said of the non-acronym name. “It’s the MILO Institute. It sounded good.”)

The idea of trying to raise money from non-government sources for space science missions is not new, but doesn’t have a favorable track record. In 2012, the B612 Foundation announced plans for a space telescope mission called Sentinel to search for near Earth objects (see “A private effort to watch the skies”, The Space Review, July 2, 2012), but by last year set aside that mission—which had a proposed cost of about half a billion dollars—in favor of alternative approaches involving smallsats and analysis of data from terrestrial telescopes. The BoldlyGo Institute has also sought to raise money for space missions, but has made little progress funding those concepts (see “Seeking private funding for space science”, The Space Review, July 10, 2017).

What makes The MILO Institute different? “There is that risk,” Bell acknowledged, but cited the support from Lockheed Martin and other partners as why he felt this effort could be more successful. “It may or may not work. We’re going to test it.”

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.