Red Moon revisitedby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Back in 2005, if you read numerous articles about the Chinese space program, you would have noticed various authors claiming that China was going to land taikonauts on the Moon in 2017, and at least one article claimed this would happen as early as 2010. |

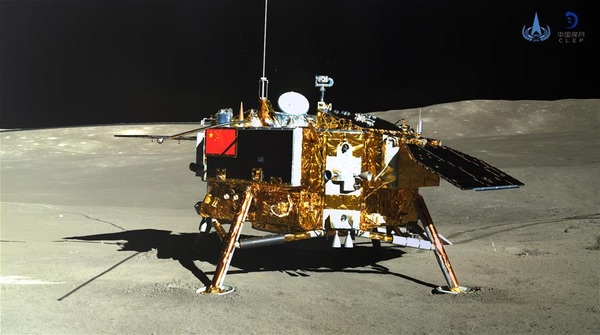

Unfortunately, today’s reporting and pontificating about China’s civil space program is filled with similar distortions which have far more to do with the biases of the writers than what is actually happening with China’s civilian space program. After the landing of China’s Chang’e-4 spacecraft on the lunar farside in early January, there were numerous articles making extravagant claims about what this event meant and how it was a harbinger of future Chinese activities. Sometimes, the same writers making bad claims about China today were making bad claims back in 2005.

Opinion-based articles about the recent Chinese lunar landing have often fallen into several broad categories:

- China is “racing” the United States, or its Asian neighbors

- China is seizing strategic “lunar high ground” that will give it a military advantage

- China is planning on developing/exploiting/seizing lunar resources that will give it an advantage in space in coming decades

- China is developing capabilities in cislunar space that give it a strategic military advantage

Often these claims have overlapped, or been expressed by the same authors in different forums. For instance, Namrata Goswami wrote in The Space Review that China was planning on setting up a base on the Moon to eventually mine resources there. (See “Why the Chang’e-4 Moon landing is unique,” The Space Review, January 14, 2019). Dr. Goswami asserted that “A research base on the Moon, with industrial capacity to build and support spacecraft using lunar resources, such as water for rocket propellant, will bring down costs of interplanetary travel.”

Only a few days earlier, Dr. Goswami had an opinion article in The Washington Post casting recent events in terms of a space race that the US was badly losing, claiming that Americans were blind to reality. That article asserted that “The United States is disorganized regarding space and cannot offer a serious challenge to the long-term plans China is setting in this domain. Neither the American people nor the U.S. military seems to perceive the significance of what China is doing strategically in the Earth-moon space. They see it through the lens of their own Cold War experience, assuming the motivations China harbors are akin to that of the erstwhile U.S.S.R. — for global prestige and simply ticking of boxes — when they are not.”

She added: “At stake isn’t simply prestige here on Earth: It’s whether the future of space exploration, resource development and colonization will be democratic or dominated by the Communist Party of China and the People’s Liberation Army of China.” Notably, Goswami presented only two options: that the Chinese are pursuing global prestige “and simply ticking… boxes,” or, as she sees it, they are pursuing “resource development and colonization.” But what some may see as American disorganization, others will interpret as the normal constructive chaos of a competitive entrepreneurial capitalist system that has produced some amazing technological advances in recent years such as reusable rockets and cubesat constellations.

| The much more public Chinese civil space program has thus become a kind of Roschach test for writers: they see in it their fears and concerns, and equate civil space activities with military power and strategic capabilities, even when there is little evidence to support these interpretations. |

These opinion articles focus on China’s civil space programs, not their increasingly capable military space programs. Because the Chinese military space program is shrouded in secrecy, outside writers know little about it. The much more public Chinese civil space program has thus become a kind of Roschach test for writers: they see in it their fears and concerns, and equate civil space activities with military power and strategic capabilities, even when there is little evidence to support these interpretations. Many authors never even consider alternative explanations for Chinese civil space activities, such as that China is pursuing a broad-based space exploration and science program—exactly what the Chinese say they are doing.

Around and around we go

This view that China’s civil space efforts somehow indicate nefarious intent has been appearing for two decades now, ever since China started its human spaceflight program. The first Shenzhou spacecraft was launched in November 1999, followed by several more un-piloted spacecraft, leading to Shenzhou 5 carrying Yang Liwei into orbit in October 2003. During this early period, it was common for articles in the Western press to refer to the military nature of Shenzhou, based upon the fact that it was managed by the People’s Liberation Army. But beyond vaguely ominous warnings, they never explained what military advantage China would obtain with a piloted spacecraft, especially since both the United States and Russia had long ago concluded that crewed military space missions were pointless. The United States canceled its Manned Orbiting Laboratory in the late 1960s, and the Soviets canceled their military Almaz space stations by the early 1980s.

There was in fact a practical explanation for PLA involvement in Shenzhou: it was one of the few Chinese government organizations with the ability to manage large technological projects. But efforts by some writers to portray China’s human spaceflight capability as threatening—particularly during the period after the 2003 Columbia accident when the US space shuttle was grounded—ran into the problem that the pace of China’s program was so slow. In almost two decades of Shenzhou flights, China has only flown six crewed missions. Each flight has demonstrated significantly improved capabilities. But when the flights happened two or three years apart, they did not fit a narrative of a racing or menacing Chinese human spaceflight capability. Thus, some writers soon turned to a new interpretation about Chinese human spaceflight: China was going to send humans to the Moon.

After President George W. Bush in 2004 announced plans to return Americans to the Moon, some writers began to look for new evidence that China was also seeking to send humans to the Moon. (See “Mysterious dragon: myth and reality of the Chinese space program,” The Space Review, November 7, 2005) Because the Vision for Space Exploration called for a Moon landing by 2018, reporters sometimes claimed to have discovered indications that China was going to land a human on the Moon by 2017, “beating” the Americans there—ignoring the fact that Americans had already been there decades earlier. (See “Red Moon. Dark Moon.” The Space Review, October 11, 2005)

Around this same time—2005 to 2007—China became much more public about its human spaceflight and space science plans. Chinese space officials began discussing the country’s plans to fly more human missions over the next decade, leading up to the fielding of a multi-segment low Earth orbit space station by the 2020s. They also began announcing future Earth science, astrophysics, solar science, and planetary exploration projects. By 2010, China was announcing plans for a broad-based civilian space science effort. This made perfect sense: China’s leadership wants the country to be a world power and to be perceived as a world power, not only militarily and economically, but technically and scientifically. That requires demonstrating civil space capabilities and participating in international science conferences.

In retrospect, when looking back at the last decade and a half of Chinese human and space science efforts, it is remarkable how open the Chinese government and space science organizations were about their plans. During a series of public presentations starting around 2006, Chinese officials explained their interest in gradually building up human spaceflight capabilities towards the goal of developing a low Earth orbit space station for the 2020s. They have been far more transparent than the Soviet Union ever was during the Cold War.

But despite the relative openness of Chinese officials about their plans, some writers chose to latch on to Chinese internet reports about Chinese lunar plans as evidence that China was planning on sending humans to the Moon in a “race” with NASA, ignoring or distorting the evidence they found. And it wasn’t just writers: members of Congress also warned of a “race” to the Moon with China. In fall 2005, Congressman Ken Calvert, chairman of the House Space and Aeronautics Subcommittee, told a reporter for Aerospace Daily & Defense Report: “I’ve been talking to a number of people that are much more knowledgeable about that than I am, [about] some things that maybe are still classified, but they believe that the Chinese are probably on the mark to get there sooner.” In March 2006, another member of Congress declared, “We have a space race going on right now and the American people are totally unaware of all this.” (See “China, competition, and cooperation,” The Space Review, April 10, 2006) This talk about “racing” China to the Moon continued for several years. In November 2007, Reuters reported that a Chinese scientist had stated that China was going to land a man on the Moon by 2017. This was a distortion of China’s announced robotic lunar sample return mission.

| China’s leadership wants the country to be a world power and to be perceived as a world power, not only militarily and economically, but technically and scientifically. That requires demonstrating civil space capabilities and participating in international science conferences. |

Around that same time it became common for some writers to claim that China had a human lunar program, despite frequent Chinese references to their plans to spend the 2020s operating their low Earth orbit space station. Although some Chinese officials indicated that they were evaluating large rockets for possible future human lunar missions, they also stated that a decision about sending humans to the Moon was unlikely to be made until the latter 2020s, after China had operated its space station and gained experience with longer duration human spaceflight. Furthermore, Chinese officials occasionally specifically declared that they were not in a race with the United States. This was, according to one US-based China expert, not because they feared they would lose, but because they had learned the lesson of what happened with the Soviet Union and the American Strategic Defense Initiative in the 1980s, when the Soviets ended up spending a huge amount of money responding to a program that never seriously threatened them.

There were explanations for some of this misleading reporting. One obvious reason was bad translations: people saw “mission to the Moon in 2017” and didn’t see, or mis-translated, the parts about it being a robotic mission. Another reason was that China’s media exploded with new entrants, many of them little more than tabloid reporting. There was a tremendous amount of content being produced for the Chinese internet in the past decade and little way to understand the reliability of many sources. Often what happened was an internet version of the children’s game “telephone” (which the British call “Chinese whispers”) where a story gets distorted the more it gets told—the first time “robotic” is left off of discussion of a Chinese lunar mission it quickly transforms into a “human lunar program.”

A major problem was and has been with the people doing the writing and pontificating—they are inserting their own agendas into their interpretation of what they saw. During the early days of the Vision for Space Exploration, a common agenda was to try and use the “threat” of a potential Chinese human lunar mission to prompt people to support NASA’s plans to send humans back to the Moon.

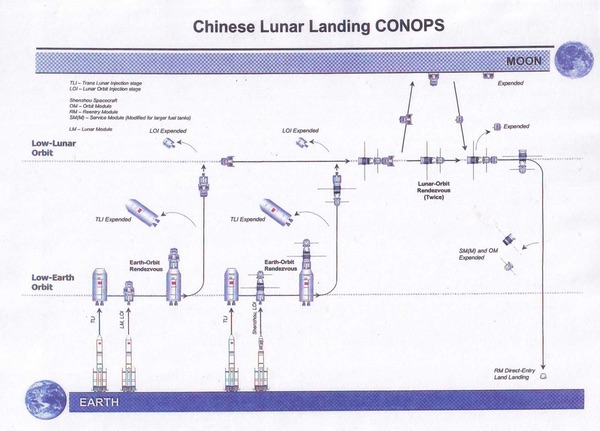

People in the west have demonstrated a remarkable ability to see what they want to see, even when it is not there. In 2008, a NASA official presented a notional chart of how China could possibly mount a mission to the Moon using many of its existing assets and avoiding the use of a large launch vehicle. (See “The new path to space: India and China enter the game,” The Space Review, October 13, 2008) In that case, not only was a NASA official using a potential Chinese Moon mission for propaganda advantage, but American critics of NASA’s lunar plans seized upon this hypothetical mission architecture as “proof” that NASA did not need a large Ares V rocket in order to return astronauts to the Moon and could do things the Chinese way. None of these rhetorical claims were ultimately sustainable: once it was clear that China was not planning on sending humans to the Moon anytime soon, the “threat” would be exposed as empty.

A NASA chart from 2008 that illustrated how China could land humans on the Moon using the Long March 5 rocket. (credit: NASA) |

No matter where you go, there you are

Something that becomes clear about the Chinese space program after long observation is that the Chinese generally do what they say they are going to do. But that presents two challenges. The first challenge is figuring out what the Chinese are officially saying about their future civil space plans. The second challenge is trying to objectively interpret Chinese civil space plans. The most effective way to determine what the Chinese are planning is to look for official presentations and statements from senior Chinese space officials. A single scientist making a statement, or a Chinese website making an assertion, is not sufficient.

| China’s extensive participation at a major, American-based planetary science conference indicates that China wants to participate in scientific discussions and to be taken seriously as a scientific leader. |

People outside of China mistakenly assume that a Chinese scientist could not speculate or talk about potential future space missions unless their statements had been officially cleared by the government. That is not true, and there have been numerous examples of individual scientists offering their own opinions and speculation without official approval. For example, several Chinese scientists have talked about the goal of mining helium-3 on the Moon, something that they have clearly picked up from Western media, and is almost certainly not official Chinese policy. (See “The helium-3 incantation,” The Space Review, September 28, 2015)

What we have also seen over the years is that Chinese space officials have spoken at international conferences about their human spaceflight and space science plans, demonstrating increasing mastery of PowerPoint. During several appearances in the last decade they have described their future human spaceflight plans in general, although they often do not provide detailed mission information until after a mission has occurred.

The cover of a recent issue of the BBC magazine Science Focus is part of the latest media push to play up a perceived race to the Moon involving China. |

Racing in place

Chinese space officials have also outlined their robotic lunar plans, and by now they have demonstrated a clear pattern for these lunar missions. For example, Chang’e-3 was China’s first lander and rover mission, with a backup spacecraft apparently partially constructed by the time of the first mission. Once Chang’e-3 was successful, China then changed the plan for Chang’e-4 to accomplish a new set of objectives. Chang’e-5 is planned to be China’s first lunar sample return mission scheduled for later this year. Chang’e-6 is the backup, and if the first mission is successful, China may use Chang’e-6 to bring back samples from the lunar farside. The success of Chang’e-4 also led the Chinese to officially announce plans to proceed with Chang’e-7 and -8, apparently following the same set of prime/backup decision rules. The first mission will be for assessing resources on the lunar south pole, and if it is successful, then Chang’e-8 will take on a more ambitious mission. Thus, China has demonstrated a methodical and highly logical path for lunar science and exploration, the kind of long-range plan that American lunar scientists envy.

Despite China’s careful and methodical and long-standing plans, the “race” theme keeps emerging again and again in the western press as the first resort of lazy writers. Most recently, the BBC’s print magazine Science Focus has a cover story that declares that “A New Race to the Moon Has Begun,” with “Moon” in red letters. What nobody seems to address is that China’s lunar sample return mission, Chang’e-5, was first publicly revealed over a decade ago and is actually two years behind the original plan. If China is “racing,” they’re doing it very deliberately, and telegraphing their moves.

Although some writers outside of China have tried to link that country’s robotic lunar program to a plan to explore and then exploit lunar resources, or to develop militarily useful space capabilities, their evidence for this is thin, and doing so requires ignoring substantial evidence that this is actually part of a scientific program. The Chinese have for many years now discussed these robotic lunar missions in terms of science, and indicated that they also plan on sending robotic missions to Mars. In 2018, dozens of Chinese planetary scientists presented their results at a scientific conference in Houston, and some are planning to present again next week. Their extensive participation at a major, American-based planetary science conference indicates that China wants to participate in scientific discussions and to be taken seriously as a scientific leader.

Why does this matter? Because effective decision-making, and any potential American response, should not be based upon bad or distorted assessments of what is really happening. At a conference on China’s space program held in Washington in the fall of 2005, several expert observers of China’s military and space programs noted that back then the Chinese tried to read everything they could about the American space program. The problem was that they also tended to believe everything that they read. The same thing happened on the American side as well, and unfortunately that tendency to believe everything still holds true among some writers. But there’s an old saying that when you hear hooves, think horses, not zebras. Alas, too many writers about China’s civil space program are hearing what they want to hear, seeing what they want to see, and not focusing on what is actually there.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.