Shaking up the commercial space station industryby Jeff Foust

|

| “Although we’ve made a significant amount of progress and understood the business case,” Northrop’s Krein said, “there was just a stronger case to be made for a combination of the talents, expertise, and subject matter experts with ourselves, Voyager, and their partners.” |

On October 4, Northrop Grumman, one of three companies that received NASA awards through the Commercial LEO Destinations, or CLD, program in late 2021 to support design work on commercial stations, announced it was abandoning plans to develop its own station. Instead, it was teaming with Voyager Space, another company with a NASA CLD award, on that company’s Starlab station.

Under the partnership, Northrop said the companies would work together to develop a version of the Cygnus cargo spacecraft that could autonomously dock with Starlab; Cygnus spacecraft on missions to the International Space Station today have to be grappled and berthed by the station’s robotic arm. The companies said they would “further explore opportunities” for additional support for Starlab.

Northrop entered the CLD program as by far the largest and most experienced space company pursuing a commercial space station. It had expertise from Cygnus and other projects, like the HALO module it is building for NASA’s lunar Gateway, and had substantial corporate resources it could have devoted to a commercial space station: the company reported last week net earnings of $937 million in just the last quarter.

However, there had been speculation that Northrop, despite its technical and financial resources, was having problems making the business case for a station close. Company executives had suggested in the past difficulties in identifying customers, as well as uncertainties in how ISS international partners would use the station and unresolved regulatory and liability issues.

Steve Krein, vice president of civil and commercial space at Northrop Grumman, said in an interview after the announcement that the partnership emerged from conversations his company had with Voyager Space about using Cygnus to support Starlab. “We started talking about if we could combine the best elements of both teams—our cargo logistics and human spaceflight experience with the capabilities of Voyager—to develop what I’ll call the ‘dream team,’” he said.

He said that the two companies, working together, could provide greater assurance to NASA that a station would be ready before the ISS is retired at the end of the decade. “Although we’ve made a significant amount of progress and understood the business case,” he said, “there was just a stronger case to be made for a combination of the talents, expertise, and subject matter experts with ourselves, Voyager, and their partners.”

Voyager Space CEO Dylan Taylor said in the same interview that his company was looking forward to taking advantage of Northrop’s expertise. “We have a good relationship with Northrop,” he said. “We were in a position to have a conversation with them regarding how they might be able to help our project along.”

The partnership was part of an inevitable process, he added. “It’s natural that there will be consolidation of skill sets and talent in the commercialization of private space stations in LEO.”

NASA took a similar view. “This is a positive development for the commercial low Earth orbit destinations effort,” said Phil McAlister, director of commercial space at NASA Headquarters, in an agency statement. “We continue to see a strong competitive landscape for future commercial destinations, and I am pleased that Northrop is staying with the program.”

By joining forces with Voyager Space, Northrop is terminating its funded Space Act Agreement with NASA after receiving $36.6 million of the $125.6 million originally awarded in late 2021. The unused funds, NASA said, will be reallocated to other companies with NASA agreements, including Voyager Space, in the form of additional milestones in their Space Act Agreements.

The third company that received a CLD award, alongside Northrop and Voyager, was Blue Origin. It is teamed with Sierra Space and other companies on the Orbital Reef commercial space station concept they unveiled two years ago (see “The commercial space station race”, The Space Review, November 1, 2021).

In recent weeks, though, there have been reports that the Orbital Reef concept, or the partnership between Blue Origin and Sierra Space, may be in trouble. Blue Origin reportedly shifted many of its employees working on Orbital Reef to other projects, like its Blue Moon lunar lander, while also considering splitting up with Sierra Space.

Publicly, Blue Origin says there is no change in its interest in Orbital Reef or its partnership with Sierra Space. “We continue to make progress on our Commercial Destinations Space Act Agreement with NASA,” the company said in one social media post.

| “Blue Origin has a heavy-lift vehicle in New Glenn. We have a transportation system for crew and cargo with Dream Chaser. We’re working together to build a space station,” said Sierra Space’s Kavandi. |

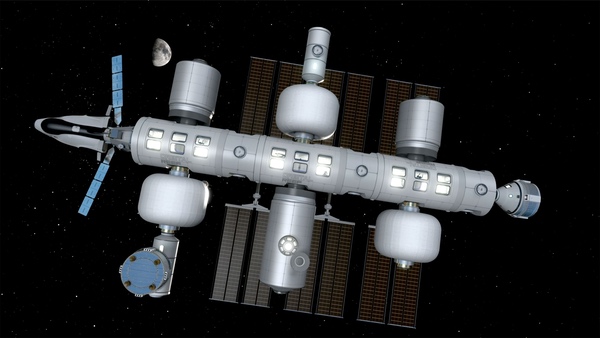

“We’re fully committed to working with NASA to ensure a continued human presence in low Earth orbit. @SierraSpaceCo is a big part of this effort and continues to provide deliverables for our NASA CLD Phase 1 contract,” the company said in another post, featuring an illustration of Orbital Reef that included Sierra Space’s inflatable modules and Dream Chaser spacecraft. “We’re all in on CLD Phase 2.”

Sierra Space has also signaled its continued cooperation with Blue Origin on Orbital Reef. “Blue Origin has a heavy-lift vehicle in New Glenn. We have a transportation system for crew and cargo with Dream Chaser. We’re working together to build a space station,” said Janet Kavandi, president and chief science officer at Sierra Space, during a panel discussion at AIAA’s ASCEND conference in Las Vegas last week. “It’s a very complementary system. It work out really well, taking advantage of all those different capabilities.”

Orbital Reef, though, won’t necessarily be the first commercial space station Sierra Space in involved with. The company has discussed creating a “Pathfinder” station using one of its LIFE inflatable modules, supported by Dream Chaser, that could be used to host commercial research.

“There have been a number of breakthroughs in the biotech world utilizing the ISS that show we can do some very unique things,” Tom Vice, CEO of Sierra Space, said of that Pathfinder station at an investors conference in June. The station, which could launch as soon as the end of 2026, would reduce risk for Orbital Reef but also be, in his words, “a revenue-generating space station that is focused around next-generation breakthroughs.”

Sierra Space also won an unfunded NASA Space Act Agreement in June, part of the agency’s Collaborations for Commercial Space Capabilities-2 (CCSC-2) initiative. That agreement will allow the company to tap into NASA expertise for that Pathfinder station after the agency concluded there was not significant overlap with Orbital Reef.

Ken Shields, senior director business development of in-space R&D, manufacturing, and emerging markets at Sierra Space, said during a panel at the American Astronautical Society’s von Braun Space Exploration Symposium last week that a LIFE module could be outfitted and be ready for crews two launches after the module itself was launched. But he also emphasized his company’s continued work with Blue Origin on Orbital Reef.

“We are making great progress on that,” he said, with a preliminary design review scheduled for mid-2024. “We’re leaning heavily into developing these commercial markets.”

Blue Origin says it is “fully committed” to the Orbital Reef space station in cooperation with Sierra Space amid reports its interest in the project and/or partnership is fading. (credit: Blue Origin) |

Business and budget uncertainties

The competition for commercial space stations goes beyond the companies with NASA CLD awards and Axiom Space, which has a separate agreement with NASA allowing it to attach commercial modules to the ISS as a precursor to a commercial station. Several other companies that are also interested in commercial stations won CCSC-2 agreements in June, such as Think Orbital and Vast, as well as SpaceX, which is examining whether its Starship vehicles could be converted into stations. Still others, like Above:Orbital, Gravitics, and Space Villages, submitted proposals for CCSC-2 awards but were not selected by NASA.

| “The panel, being watchful of this extremely tight schedule, remains concerned that there is not yet a clear, robust business case for commercial LEO nor clear evidence of the financial viability” of the proposed stations, West said. |

Vast, for example, plans to use its CCSC-2 award to better understand NASA’s needs ahead of the next phase of the CLD program. It is working on a single-module commercial station called Haven-1 intended to support short-duration visits while it works on larger stations it will offer to NASA and others (see “A vastly different approach to space stations”, The Space Review, May 15, 2023). “It is our proof point that we can build an actual commercial space station, we can have a crew visit it,” Max Haot, CEO of Vast, said on the ASCEND panel. The company is working on a “CLD-compliant” station concept he said Vast would announce soon.

The number of companies pursuing commercial space stations, either with or without NASA support, is far greater than even the most optimistic projections of demand for them in the foreseeable future. That’s particularly true when many are betting on a post-ISS NASA to be the major customer for their stations.

“NASA would be the anchor tenant,” said Randy Lillard, Orbital Reef program manager at Blue Origin, on the ASCEND panel. “Their requirements define the initial space station and how it’s going to work. People are going to come once NASA starts flying.”

Uncertainty about commercial space station business plans has made its way to NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel (ASAP). At its public meeting last week, members said they were concerned about the schedule and viability of those stations, which are critical in NASA’s plans to maintain a presence in LEO after the ISS.

“NASA should develop a comprehensive understanding of the resources and timelines of the ISS-to-commercial-LEO transition plan to a much higher level of fidelity, to provide confidence that the nation will be able to sustain a continuous human presence in LEO,” ASAP member David West said at the meeting, a recommendation backed by the full panel.

He noted NASA already has a “very tight” schedule in the CLD program to get at least one commercial station flying by the end of the decade. He suggested ASAP members were not yet convinced any of them had a business case that closed.

“The panel, being watchful of this extremely tight schedule, remains concerned that there is not yet a clear, robust business case for commercial LEO nor clear evidence of the financial viability” of the proposed stations, he said, “creating programmatic and safety risks with the entire plan for NASA LEO.”

The plan that ASAP recommends NASA develop, West said, “should be grounded in explicit defensible assumptions and should include quantifiable metrics and progress deadlines for ensuring that the market for commercial LEO activities exists and is sufficient to support the development, production, and operation of one or more commercial platforms to replace the ISS.”

Commercial space station developers, at least those working with NASA, are dealing with an additional degree of uncertainty. NASA requested $228.4 million for the CLD program in fiscal year 2024, projecting that to grow to more than $435 million in 2028. But that budget proposal predated a deal between Congress and the White House that caps non-defense discretionary spending—including NASA—at 2023 levels in 2024 with just a 1% increase in 2025.

| “The day will inevitably come when the station is at its end of life and we may not be able to dictate that date,” Sanders said about the deorbit vehicle. “This needs to be resourced, and resourced now, if we are to avert a catastrophe.” |

NASA officials have stated that they expect to get no more than 2023 funding levels in 2024, but the impacts on specific programs remains to be determined. Some in industry are privately worried that CLD will see its budget cut compared to those projections, further jeopardizing plans to have a station ready by the end of the decade.

“NASA has a very full mission plate. To the extent that their budget request is not fully funded, the leadership will need to make critical decisions,” said Patricia Sanders, chair of ASAP, at her committee’s meeting last week. “Either program content or schedules will need to be adjusted to meet fiscal realities.”

One NASA project that should proceed despite those fiscal realities, the panel said, was not CLD but instead the US Deorbit Vehicle (USDV), a spacecraft that would dock to the ISS and handle the final phases of its deorbiting into the South Pacific. NASA is seeking $180 million for USDV in 2024 and expects the project’s overall cost to approach $1 billion.

“The panel feels strongly and will continue to emphasize that funding the deorbit vehicle is not optional and it cannot be delayed,” West said. “It must be adequately funded in a timely fashion to provide the means for safely disposing of the ISS.”

“The day will inevitably come when the station is at its end of life and we may not be able to dictate that date,” Sanders added about the deorbit vehicle. “This needs to be resourced, and resourced now, if we are to avert a catastrophe.”

NASA may be preparing for a scenario where the deorbit vehicle is funded on schedule while commercial space stations suffer delays because of budget cuts or other problems. The request for proposals for USDV, released in September, is for a base contract for the USDV that runs through March 2031. However, the contract will include options that would stretch out the operations of USDV through as late as September 2035—just in case, it appears, if the commercial space station industry gets a little too chaotic.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.