Titan’s spinners: the FARRAH satellitesby Dwayne A. Day

|

Two versions of the FARRAH signals intelligence satellites from a recently declassified document. The rectangular satellite was about the size of a large suitcase. Several were launched in the early 1980s from the sides of HEXAGON photo-reconnaissance satellites. The "tuna can" shape was a later version. It was originally designed to be launched from the Space Shuttle, but was later diverted to launch on refurbished Titan II ICBMs. (credit: NRO) |

Hitchhikers

Starting in the early 1960s, the United States Air Force began tossing small satellites off the sides of rockets launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base. The satellites were about the size and shape of a large suitcase, and one of them was given the nickname “Hitchhiker.” They were built by Lockheed, which designated them Program 11, or P-11 for short. After being pushed off the back of an American photo-reconnaissance satellite, the satellites started spinning and fired a small rocket motor that boosted them to a higher orbit. As they spun, they deployed an array of antennas that swept over the face of the Earth as the satellites orbited the poles.

| Throughout the 1960s and 1970s the satellites were deployed rarely, initially only a few times a year, then by the 1970s once every other year or so. By then they were designated Program 989 satellites, and by the later 1970s, the satellites had been given the codename FARRAH, after actress Farrah Fawcett. |

Their antennas were designed to detect various emitters on the ground, depending upon the mission. Their primary targets were radars inside the Soviet Union, initially air search radars of the type used to detect enemy (in the Soviet case, that meant American) aircraft. But soon the satellites were adapted to detect more elusive and enigmatic emitters, such as the giant radars, hundreds of meters long, used to track American ballistic missiles so that they could be intercepted, or to detect American satellites in orbit. They would record signals while over the Soviet Union, then play them back over a ground station within the United States (see “Big bird, little bird: chasing Soviet anti-ballistic missile radars in the 1960s,” The Space Review, December 14, 2020.)

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s the satellites were deployed rarely, initially only a few times a year, then by the 1970s once every other year or so. By then they were designated Program 989 satellites, and by the later 1970s, the satellites had been given the codename FARRAH, after actress Farrah Fawcett (see “FARRAH, the superstar satellite,” The Space Review, April 15, 2024.) Whereas they had initially been developed to serve strategic needs, providing data that was used to design weapons systems and to defend strategic bombers like the B-52 Stratofortress, by the late 1970s the satellites were beginning to serve tactical users, like deployed Army and Air Force units in Europe and Korea (see “Little Wizards: Signals intelligence satellites during the Cold War,” The Space Review, August 2, 2021, and “From the sky to the mud: TENCAP and adapting national reconnaissance systems to tactical operations,” The Space Review, June 19, 2023.) As computing power increased, it became possible to process the satellite data in near-real-time rather than weeks or months, and thus an Army operator sitting at a terminal could very quickly gather data about the dispersal of mobile radar units inside Warsaw Pact nations.

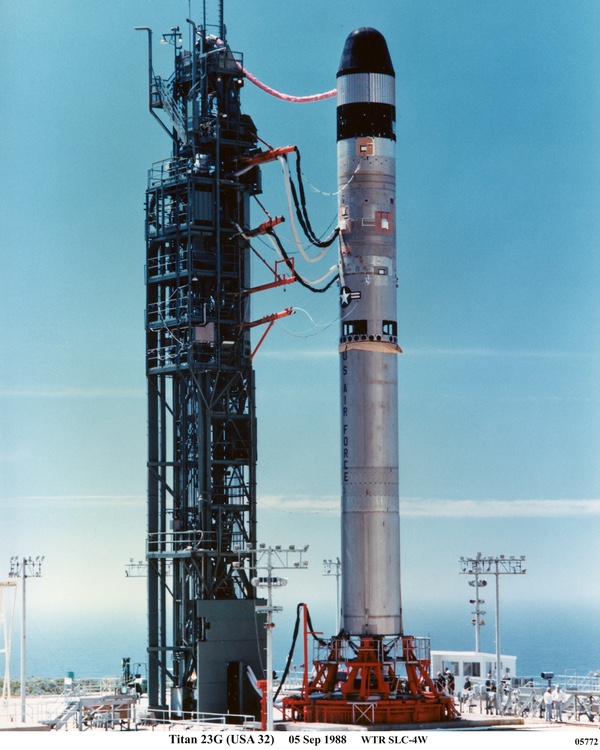

The decommissioning of Titan II ICBMs in the 1980s made them available as satellite launchers. Here a Titan II is poised to launch the first of the late model FARRAH signals intelligence satellites. Three FARRAHs were launched on Titan IIs. The rockets were also used to launch other payloads, such as meteorological satellites. (credit: Peter Hunter Collection) |

Enter the shuttle

By the late 1970s, the National Reconnaissance Office, which managed the US fleet of intelligence collecting satellites, was moving many of its satellites from expendable launch vehicles to the Space Shuttle. Many of the details of these transfers remain classified, although declassified interviews and an official history indicate that there was a debate within the NRO about whether to simply move existing spacecraft onto the new launch vehicle with minimal modification, or to redesign them to take advantage of the shuttle’s greater capabilities, such as making the satellites larger, or even designing them to be serviced in space, like the Hubble Space Telescope.

According to the person who was in charge of Program 989 in the early 1980s, the NRO made two decisions regarding the satellites. The first was to make them significantly larger than their suitcase-sized predecessors, changing the shape from a rectangle to a spinning “tuna can” with multiple antennas that would be deployed from its top. The second was to co-manifest them with a Navy ocean surveillance satellite on shuttle flights, presumably because they would launch to similar orbits from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California (see “Buccaneers of the high frontier: Program 989 SIGINT satellites from the ABM hunt to the Falklands War to the space shuttle,” The Space Review, Monday, November 7, 2022.)

The co-manifesting decision presented a dilemma: the shuttle did not then have sufficient payload capability to carry both payloads without significant upgrades, including a new lightweight external tank and lightweight solid rocket boosters (SRBs) made of a carbon filament. Those upgrades would have to be funded and then successfully implemented. That was going to take time and money.

| At some point the program office decided to procure a mockup of the satellite for handling tests at the launch site. No information is public about when or how this decision was made, but crude mockups—often referred to as boilerplates—have existed throughout the history of the space program . |

Program manager Jon Bryson knew that if push came to shove, his Program 989 satellites would be removed from the shuttle before the Navy satellites. He needed another way to get them to orbit. Soon he found another option. The Air Force was withdrawing dozens of Titan II ICBMs from silos around the country, which could be converted into launch vehicles. There was already a plan to move the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program satellites from the shuttle to the Titan II, and adding the Program 989 satellites improved the justification for converting the ICBMs.

Once the decision was made to switch the satellites to the Titan II, the Titan II program office became involved and many decisions had to be made on how to handle the satellites at the launch site and put them atop the launch vehicle. At some point the program office decided to procure a mockup of the satellite for handling tests at the launch site. No information is public about when or how this decision was made, but crude mockups—often referred to as boilerplates—have existed throughout the history of the space program to serve a variety of ground handling requirements. During the Apollo program, Apollo Command Module boilerplates were used for training rescue swimmers to attach the flotation collar in the ocean, aircraft carrier crews to lift them out of the water, and ground crews to move the spacecraft inside the assembly building.

The first of the larger Program 989 satellites was stacked atop its Titan II launch vehicle and launched from Vandenberg on September 5, 1988. At the time this was the first use of a new rocket for a classified payload and it confused independent observers who nevertheless managed to track the spinning satellite in its low Earth orbit. Observers guessed at its mission, and some got it right whereas others did not.

Almost exactly one year later, on September 6, 1989, a second Titan II launched from Vandenberg carrying the second satellite into orbit. But this proved to be an eventful mission. The satellite separated from the rocket but then failed to turn on. Ground controllers sent multiple commands to it, but it never activated. According to somebody involved in the program, the failure was ultimately traced to the safety system originally incorporated for shuttle launch. That system kept the satellite electronically dormant while in the shuttle’s payload bay and turned it on after it was deployed. But a mistake failed to account for the switch to the Titan II, and the satellite never activated as it should have after deployment.

On April 25, 1992, a third satellite was launched atop a Titan II. This one apparently operated successfully. There were rumors that three additional Titan IIs were allocated to classified launches that were later canceled, but there is no way to confirm this. At some point the pathfinder vehicle was declared as unneeded equipment and was donated to the Santa Maria Museum of Flight. It sat there for decades, without a label, and almost nobody knowing what it was for until now.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.